Abstract

This paper presents an analysis of a particular clinical agency’s approach to treating depression. Specifically, its population health and case management processes are described. An evidence-based clinical pathway by the National Institute of Healthcare and Excellence of the United Kingdom is then applied to a case from the agency. The results indicate that the pathway proposes a cost-effective way of managing depression with the help of evidence-based treatments and with provisions for variances, corrections, and post-discharge activities. While it is an example of a disease management tool, the pathway is in line with the agency’s decisions on the patient’s care and could be integrated into its case management approach.

Introduction

One of the health concerns that the patients of a small psychiatric practice commonly request assistance with is depression. The present paper will consider the practice’s approach and processes related to this problem. Then, an external clinical pathway for depression management will be introduced and applied to a patient’s case. The exercise demonstrates that the application of clinical pathways can provide some insights into the processes that are present during the management of a particular condition. In addition, the pathway is cost-effective and could potentially be used by the practice as a part of its case management approach.

Disease Process Identification and the Practice’s Approach to It

The choice of depression for this paper is explained by its prevalence. It is generally a widespread issue with significant negative consequences (Grover, Gautam, Jain, Gautam, & Vahia, 2017), but it is also common among the patients of the described clinical agency. An element of the population health approach to depression can be found in the way the agency distributes information about many common health concerns, including depression, through its handouts and posters, which are regularly revised.

The materials can enhance the patients’ awareness of the illness and its treatment options. Therefore, such methods could be considered a population-based care approach which may assist patients in recognizing and managing the disease process (Fink-Samnick & Treiger, 2018). However, the primary approach of the practice is case management. This choice is justified by the prevalence of aging patients who often have particular needs.

Indeed, the clinical agency works to ensure that an individual patient’s needs are met through the collaborative effort of the staff. The associated processes include assessment and diagnosing, treatment plan development and negotiation, and monitoring, which are some of the common elements of depression management (Grover et al., 2017), as well as case management (Fink-Samnick & Treiger, 2018). The agency offers patient education and treatment options, including drug prescription and group and individual psychotherapy. Thus, some processes help the agency provide care for individuals and groups with depression with a focus on finding tailored solutions for patients with different needs, abilities, and resources.

Clinical Pathway Location

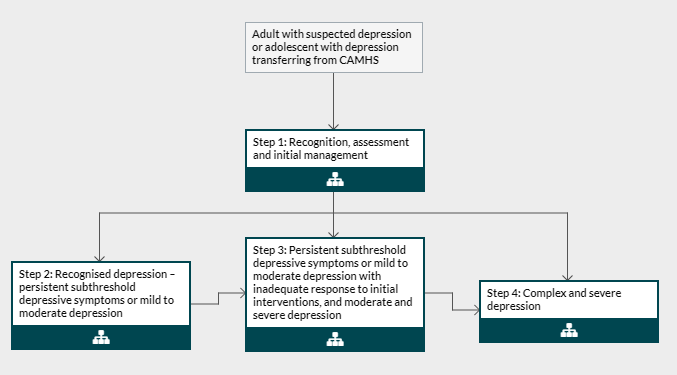

The described practice does not have a document that could be considered a clinical pathway for depression. However, the National Institute of Healthcare and Excellence [NICE] (n.d.), which is a United Kingdom governmental body tasked with researching and developing health guidance, presents clinical pathways in the form of interactive charts with detailed commentary. The main flowchart of NICE (n.d.) that is devoted to depression is present in Appendix A. Its recommendations appear to correspond to the currently acknowledged best practices and other guidelines (Grover et al., 2017; Straten, Hill, Richards, & Cuijpers, 2015). This pathway tool seems to be meant for disease management, but it can be integrated into a case management approach as well.

Pathway Application

Even though the pathway is not used by the described practice, it can still be applied to its patients. A recently visiting older woman, for example, reported symptoms of unusually depressed moods, which caused her significant distress. The first step of the pathway consists of recognizing the possibility of the woman having a depressive episode, which can be confirmed or disproven with the help of the assessment. Such procedures were carried out in the described case, and, according to NICE (n.d.), the following steps are determined by the results of the assessment.

Thus, for an assessment that reveals the depression that is moderate or mild, the second step is supposed to follow. In it, some advice is to be provided to the patient with a discussion of the possible treatment options. According to the information available for this paper, the woman’s depression was assessed as mild, and she decided to take part in group therapy. These procedures and decisions are in line with NICE’s (n.d.) recommendations to attempt to manage mild-to-moderate depression with psychotherapy before introducing any drugs. Thus, the woman’s case involved the completion of the first and second steps of NICE’s (n.d.) clinical pathway. It is expected that she will be visiting the practice to establish the effectiveness of the intervention, as well as for monitoring and post-discharge care.

Certain variances of the case and corrective measures should be considered as well. Variations are usually caused by an inadequate response to treatment; if the woman exhibits it, NICE (n.d.) directs care providers to the third step, which exists for the depression that is severe or persistent. The possible treatments include high-intensity psychological interventions, medications, or a combination of both. If the solutions demonstrate improvement, the patient is to be continually managed with measures in place for preventing a relapse. If not, the treatment will require revision, which can include, for instance, switching or augmenting the antidepressants. The fourth step of the pathway is connected to very persistent and complex cases of depression; they do not apply to the described patient.

The services that are required after the discharge are presented with a special flowchart by NICE (n.d.). Depending on the patient’s risks, the woman is supposed to be provided with reasonable recommendations on future treatment that is intended to prevent relapse; if she takes up drug treatment, NICE (n.d.) supports the idea of continuing the medication for the period of six months to two years. Furthermore, NICE (n.d.) recommends reassessing the patient six months and two years after the remission, as well as regularly in the future if required. If a relapse does occur, NICE (n.d.) instructs to continue medication and use psychotherapy. In summary, NICE (n.d.) presents a thoroughly planned pathway that incorporates variances, corrections, and post-discharge activities.

Cost-Effectiveness

NICE’s (n.d.) flowchart uses the approach to depression management that is termed “stepped care.” There exists sufficient evidence to suggest that it is a moderately effective model, but the data on its cost-effectiveness is limited. The reports of studies include reductions in costs, as well as incremental increases and increases that were viewed as offset by health-related benefits and associated savings (Ho, Yeung, Ng, & Chan, 2016; Straten et al., 2015). Therefore, the pathway is likely to be cost-effective, but the specific outcomes cannot be guaranteed.

Conclusion

An analysis of the described clinical agency’s approach to depression care indicates that it mostly focuses on case management but also uses certain public health tactics. The agency does not employ a depression pathway, however, and the one proposed by NICE (n.d.) could potentially be helpful. Indeed, NICE (n.d.) offers a disease management tool that is in line with the agency’s general approach to managing depression. Also, the pathway is evidence-based and can be cost-effective; its flowcharts include reasonable variances, potential corrections, and post-discharge plans. Overall, the pathway offers an extensive overview of depression management processes.

References

Fink-Samnick, E., & Treiger, T. (2018). Case and population health management. In D. Huber (Ed.), Leadership and nursing care management (pp. 240-267). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Grover, S., Gautam, S., Jain, A., Gautam, M., & Vahia, V. (2017). Clinical practice guidelines for the management of depression. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 59(5), 34-50. Web.

Ho, F., Yeung, W., Ng, T., & Chan, C. (2016). The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of stepped care prevention and treatment for depressive and/or anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 1-10. Web.

National Institute of Healthcare and Excellence. (n.d.). Care for adults with depression. Web.

Straten, A., Hill, J., Richards, D., & Cuijpers, P. (2015). Stepped care treatment delivery for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 45(2), 231-246. Web.

Appendix A