Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and gastritis affect the critical functions of the stomach in food digestion. Understanding the mechanism of regular gastric acid stimulation and production is essential to study these conditions. The present paper will explain the production of gastric acid, as well as the pathophysiology, diagnostics, and treatment of GERD, PUD, and gastritis.

Normal Gastric Acid Stimulation and Production

Parietal cells play a crucial role in gastric acid secretion. These cells have receptors and are activated by hormonal, paracrine, and neural stimuli, namely M3 receptors for acetylcholine and H2 type receptors for histamine (Kopic & Geibel, 2013). Gastrin, produced by G-cells in the antral part of the stomach, also has an indirect effect on gastric acid production by stimulating ECL cells to release histamine, which, in turn, stimulates parietal cells (Kopic & Geibel, 2013). The production of gastric acid is also a rather complex process that requires several changes in parietal cells. First, the tubulovesicles containing proton pumps fuse with the canalicular surface of the cell. Using these pumps, parietal cells exchange intracellular hydrogen ions for potassium ions from the lumen of the stomach. Hydrogen is then joined by chloride ions and delivered into canaliculi in the gastric lumen, thus acidifying the contents of the stomach (Kopic & Geibel, 2013). In the absence of any abnormalities, the HCl produced as a result of this process plays a critical part in food digestion in the stomach.

GERD, PUD, and Gastritis

Influence on Gastric Acid Production

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and gastritis are often associated with hypersecretion of gastric acid. In particular, Helicobacter pylori, which are usually responsible for the development of gastritis, create an alkaline environment in the stomach, thus triggering increased gastric acid production (Waldum, Hauso, & Fossmark, 2014). Similarly, peptic ulcers often develop due to a Helicobacter pylori infection, which means that the same changes to acid production can occur in this condition (Lanas & Chan, 2017). However, Helicobacter pylori can also have the opposite effect on gastric acid production. According to Lee and McColl (2013), when the infection remains untreated, “gastric acid secretion falls with age, reducing by about 50% between the ages of 20 and 50 years of age” (p. 346). GERD, on the other hand, has a different mechanism of development and is caused by functional changes in the gastroesophageal junction. However, the action of inflammatory mediators in GERD could also be linked to increased or decreased acid production (Altomare, Guarino, Cocca, Emerenziani, & Cicala, 2013). Thus, all of these conditions can influence the production of HCl by the parietal cells.

Behavioral Factors

Eating and exercise habits, as well as care-seeking behaviors, may impact the development and course of GERD, PUD, and gastritis. Studies indicate that unhealthy eating is among the key risk factors for gastritis, and thus could also lead to PUD (Suzuki & Mori, 2016). Obesity, which is often the result of poor eating habits, is also connected to GERD (Altomare et al., 2013). Obesity can also occur due to low physical activity rates, which is why the overall lifestyle plays a vital role in the development of GERD.

Another essential behavioral factor linked to the development of these conditions is care-seeking behaviors. For instance, if a patient postpones visiting a doctor despite persistent stomach pain, heartburn, and other symptoms of inflammation, they are more likely to develop peptic ulcers due to an untreated H. pylori infection or experience the complications of gastritis and GERD, such as erosions, chronic gastritis, and bleeding (Chey, Leontiadis, Howden, & Moss, 2017).

Diagnostics and Treatment

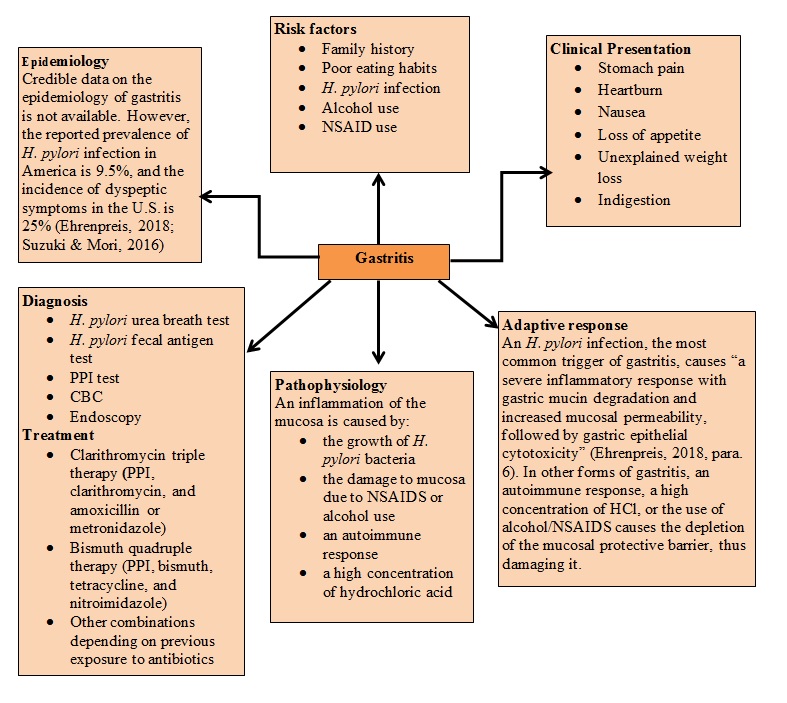

The present section will focus on diagnostic and treatment procedures applicable to patients with obesity, unhealthy eating habits, low rates of physical activity, and poor care-seeking behaviors. First of all, if the symptoms of GERD, PUD, or gastritis are suspected, it is critical to perform a diagnostic endoscopy, as well as order an H. pylori urea breath test, an H. pylori fecal antigen test, a PPI test, and a CBC (Ehrenpreis, 2018; Iwakiri et al., 2016; Satoh et al., 2016). The results of these examinations would allow us to differentiate between the three conditions and establish an appropriate course of treatment.

For gastritis or PUD associated with Helicobacter pylori, treating the infection is imperative to managing the condition. As a first-line treatment, it is recommended to prescribe a “clarithromycin triple therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin or metronidazole for 14 days” (Chey, Leontiadis, Howden, & Moss, 2017, p. 214). However, if the patient has a history of macrolide exposure, a quadruple therapy including a PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and nitroimidazole for 10–14 days is recommended (Chey et al., 2017). In the presence of peptic ulcer bleeding, endoscopic therapy, followed by medication with antacid agents should also be considered (Satoh et al., 2016). These treatments should be useful in eradicating the H. pylori infection; however, a follow-up examination in 4 weeks is required to confirm efficiency. The first line of treatment for GERD does not need an antibiotic if no H. pylori infection was detected. Iwakiri et al. (2016) recommend an 8-week course of PPI as the first-line treatment for GERD. A follow-up visit should be scheduled to determine the effectiveness and prescribe maintenance therapy.

Finally, the patient should receive education about behavioral factors affecting the progression of gastritis, GERD, and PUD. Recommendations for healthy weight loss and dietary changes should be provided. The education plan for the patient should also include information about appropriate care-seeking behaviors.

Summary

Overall, inflammatory and functional diseases of the stomach, such as GERD, PUD, and gastritis, can have an adverse influence on acid stimulation and production. Behavioral factors, such as diet, lifestyle, and health-seeking behaviors, can influence the development of gastritis, GERD, or PUD. Although an effective diagnostics and treatment could help to relieve the symptoms and eradicate the disease, it is also crucial to provide appropriate patient education on diet and lifestyle changes, as they would help to prevent and manage these conditions.

Adaptive response

An H. pylori infection, the most common trigger of gastritis, causes “a severe inflammatory response with gastric mucin degradation and increased mucosal permeability, followed by gastric epithelial cytotoxicity” (Ehrenpreis, 2018, para. 6). In other forms of gastritis, an autoimmune response, a high concentration of HCl, or the use of alcohol/NSAIDS causes the depletion of the mucosal protective barrier, thus damaging it.

References

Altomare, A., Guarino, M. P. L., Cocca, S., Emerenziani, S., & Cicala, M. (2013). Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Update on inflammation and symptom perception. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG, 19(39), 6523-6528.

Chey, W. D., Leontiadis, G. I., Howden, C. W., & Moss, S. F. (2017). ACG clinical guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 112(2), 212-239.

Ehrenpreis, E. D. (2018). Gastritis. Web.

Iwakiri, K., Kinoshita, Y., Habu, Y., Oshima, T., Manabe, N., Fujiwara, Y.,… Shimosegawa, T. (2016). Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for gastroesophageal reflux disease 2015. Journal of Gastroenterology, 51(8), 751-767.

Kopic, S., & Geibel, J. P. (2013). Gastric acid, calcium absorption, and their impact on bone health. Physiological Reviews, 93(1), 189-268.

Lanas, A., & Chan, F. K. (2017). Peptic ulcer disease. The Lancet, 390(10094), 613-624.

Lee, Y. Y., & McColl, K. E. (2013). Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 27(3), 339-351.

Satoh, K., Yoshino, J., Akamatsu, T., Itoh, T., Kato, M., Kamada, T.,… Shimosegawa, T. (2016). Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for peptic ulcer disease 2015. Journal of Gastroenterology, 51(3), 177-194.

Suzuki, H., & Mori, H. (2016). Different pathophysiology of gastritis between East and West? An Asian perspective. Inflammatory Intestinal Diseases, 1(3), 123-128.

Waldum, H. L., Hauso, Ø., & Fossmark, R. (2014). The regulation of gastric acid secretion–Clinical perspectives. Acta Physiologica, 210(2), 239-256.