Situation

The patient’s chief complaint is abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant that gets worse during the last five hours. Additional problems include nausea, appetite loss, and umbilicus pain. Pain relievers may be taken several hours earlier with no impact on the current health situation. There is no time to take additional medications in order not to increase mortality rates. Any drugs used by the patient have to be removed to develop a final diagnosis for the patient.

Solution

Acute appendicitis is approved after blood tests (an increased number of leucocytes in the blood are found). The main medications aim at eradicating infection and preventing complications. Antibiotics introduce a first-line (alternative) treatment strategy for patients with previous surgical complications (Flum, 2015). The use of antibiotics for the treatment of acute appendicitis may change the quality of life in patients. Therefore, appendectomy is a strongly recommended option with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) being taken after (Whalen, Schwartz, & Heneghan, 2017). In case of nonsurgical treatment, antibiotics are recommended under the surgeon’s control.

Drug

Many recommendations are given to support nonsurgical treatment. The Corporate Antimicrobial Stewardship Sub-Committee (CASS) (as cited in Lopansri, Stemehjem, Webb, Caraccio, & Waters, 2016) recommends amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid 875 mg PO BID along with metroNIDAZOLE 500 mg PO q8has a part of the oral regime. According to the American College of Surgeons, a higher chance of reoccurrence is frequently observed in patients who follow a nonsurgical (antibiotic) line of treatment (as cited in Flum, 2015). Antimicrobial therapy cannot be ignored by patients with appendicitis but has to be controlled by surgeons not to allow the development of serious complications and take emergency actions if necessary.

Pharmacology

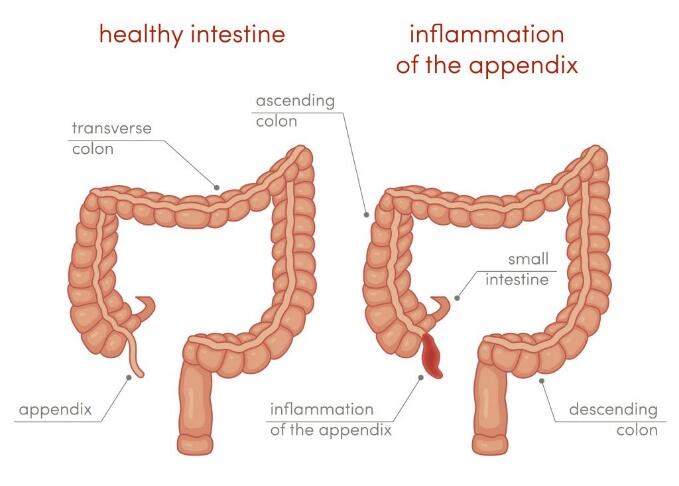

There are no clearly formulated causes of why acute appendicitis occurs. It is one of the most common reasons for abdominal emergencies around the globe. This disease has to be diagnosed fast when the appendix is suddenly inflamed with its lumen being blocked by fecaliths or other foreign bodies provoked by a viral infection in the body (Aluzri, 2018). However, true reasons for these health conditions remain unknown or poorly understood.

As can be observed in Figure 1, the obstruction of the tissue leads to increased pressure in the appendix and reduced blood flow. As a result, the presence of lymphatic tissues influences the work of the immune system and bacteria can fast spread within the body. The obstruction in the appendix also results in the creation of mucus in the organ that makes appendix walls ischemic. As soon as the appendix perforates, there are higher chances for bacteria and inflamed cells being released, and the surrounding structures like the peritoneum become damaged (Aluzri, 2018). Abdominal pain and the loss of appetite are the main signs of this type of inflammation that causes acute appendicitis.

This inflammation can easily extend to different organs, including the serosa. Arterial blood flow becomes compromised, and infraction with perforations may occur. These changes are observed in the growth of additional symptoms of acute appendicitis like nausea and vomiting (Aluzri, 2018).

Finally, the increase in serotonin that is located in the epithelium can also play an important role in the development of appendix-associated complications and inflammation in the body (Petroianu & Varroso, 2016). Serotonin releases exacerbate intraluminal secretion and induce nausea (Petroianu & Varroso, 2016). Inflammation causes different immunologic reactions, and its recognition at the early stage is required.

Physical Assessment

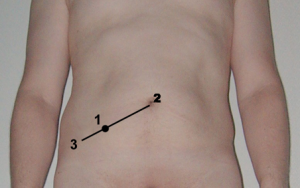

There are three main signs that have to be recognized during a physical assessment of a patient with possible appendicitis:

- McBurney’s point (as it is shown in Figure 2, the most tender part is found in this right lower quadrant where an inflamed mass should be palpable);

- Rovsing’s sign (when light palpations in the left lower quadrant elicit certain pain in the right lower quadrant);

- Dunphy’s sign (when a cough, a jump, or feet tapping increases abdominal pain in patients without any additional signs or changes).

In both male and female patients, it is expected to check the following conditions:

- Bowel sounds. They can be recognized in the abdomen. The doctor should listen to them carefully and decline the possibility of constipation (the absence of bowel sounds)

- Gentle palpations. This step helps to recognize the most painful area in the body. Patients must report on any inconvenience they experience.

- Facial expressions. The doctor should follow any facial change in a patient. In many cases, people are not able to recognize the fact of pain and report on it properly.

Physical examination is also based on the gender of patients. In male patients, genitourinary examination (groin and genitalia) excludes male health problems like hernia or testicular torsion (Aluzri, 2018). In female patients, gynecological disorders have to be excluded with the help of pelvic examination. Additional tests (blood and urine) and X-rays are recommended to find out the causes of pain, depending on the current condition of the patient (critical or not critical).

References

Aluzri, H. (2018). Acute appendicitis. Web.

Flum, D. R. (2015). Acute appendicitis – Appendectomy or the “antibiotics first” strategy. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(20), 1937-1943.

Lopansri, B., Stemehjem, E., Webb, B., Caraccio, J., & Waters, D. (2016). Clinical guideline: Antibiotic recommendations for acute appendicitis. Web.

Petroianu, A., & Varroso, T. V. V. (2016). Pathophysiology of acute appendicitis. JSM Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 4(3), 1062-1066.

Whalen, T., Schwartz, M., & Heneghan, K. (2017). Appendectomy: Surgical removal of the appendix. Web.