Introduction

The change project was initiated to decrease the time intervals of the Door to Balloon (D2B) in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) patients. In order to suggest an appropriate plan, the literature review, clinical data analysis, process for analysis as well as SMART goals were conducted in previous works. Besides, the tree diagram was created to enhance the visibility of goals. In particular, it was stated that the key goal of the project is to reduce D2B intervals lower than 60 minutes up to 45 minutes. Moreover, the project reflected potential steps concerning several fields of change including environmental and organizational issues along with the personnel training. However, it seems necessary to provide trends and gaps analysis to ensure the comprehensiveness and relevance of the topic under the study. In this connection, the paper aims to evaluate trends and gaps in analyzed data resulting in the concise identification of new information that may influence the project.

Factors Impacting the D2B

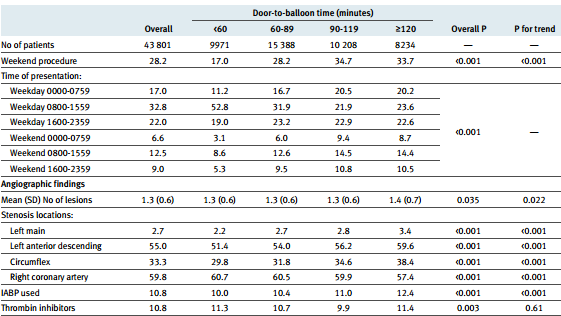

In order to assess the relationship between the D2B and hospital mortality, Rathore et al. performed an analysis of the cardiovascular register data. In 2005-2006, the register included 43 801 STEMI patients admitted in the first 12 hours of the disease patients (Rathore et al., 2010). The statistical analysis was performed in the following four categories where D2B was <60, 60-89, 90-119, and ≥120 minutes. The communication between the D2B and hospital mortality was assessed by logistic regression adjusted for such factors as gender, race, age, medical history (diabetes, left ventricular ejection fraction, and a chronic pathology light), peculiarities of the PCI (thrombin inhibitors, the operation at the weekend), and coronary anatomy).

As a result, the median of the D2B time was 83 minutes. D2B time turned out to be 14 minutes longer in the deceased patients (96 vs. 82 minutes in survivors) (Rathore et al., 2010). In multivariate analysis, the time between the D2B and mortality found a direct non-linear relationship (Figure 1). If D2B time was 30 minutes, the mortality was 3.0%, at 60 minutes – 3.5%, at 90 minutes – 4.3% at 120 minutes – 5.6% at 150 minutes – 7.0%, and at 180 minutes – 8.4% (Rathore et al., 2010). Thus, reducing the D2B time from 90 minutes to 60 minutes was associated with decreased mortality at 0.8 % and D2B reduction time from 60 minutes to 30 minutes – 0.5 %.

The results indicate the need to minimize the timing of the primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) even in those hospitals where coronary intervention is made in the currently recommended period. Accordingly, the change project goes in line with the above trend. What is more, it points out the gap of various factors analysis that might involve age, gender, and clinical symptoms. The investigation of that aspect might be of great importance and, perhaps, should be uncovered in perspective research.

Gender Issues

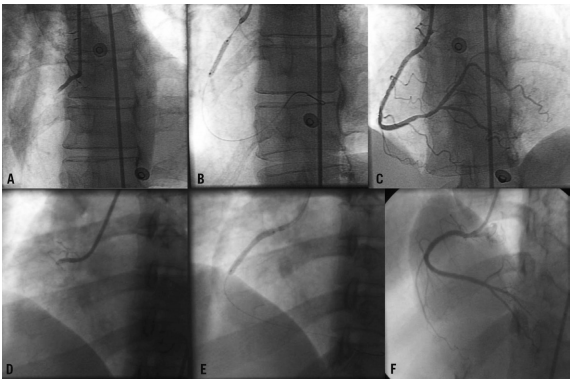

The benefits of early reperfusion in the STEMI patients of both sexes are undoubtedly high and reflected in current medical practice guidelines. In spite of that fact, the STEMI statistics show that women are less likely to be admitted to hospitals with the opportunity of PCI. According to the recent Polish study, 26035 patients (34.5% female) with the STEMI PCI received PCI earlier than 12 hours after the onset of the disease (Chieffo et al., 2012). Wherein, significant differences in the time from the development of the disease prior to PCI were marked including D2B intervals (45 (interquartile range from 30 to 70) min. vs. 44 (interquartile range from 30 to 68) min) (Chieffo et al., 2012). These results confirm the presence of not only the delay in the arrival of patients but also the physician’s delay with treatment strategy solutions. The delay in diagnosis and treatment in women with STEMI symptoms is illustrated in Figure 2.

The first line consisting of A, B, and C represents a 58-year-old woman with 14 hours of pain in the chest while the second panel of D, E, and F demonstrates a 37-year-old female with two days of pain. Both of them were treated with a good result. However, the second one was treated with two metal stents.

Seeing that the analyzed research reveals a serious impact of delays in women with the STEMI, it becomes obvious that the change project possesses a gap of separate examination of males and females as well as the age differentiation. In other words, the change project relates to the whole population whereas there might be a considerable influence of the mentioned criteria. Therefore, they are not presented in the project but might be studied later.

Feedback Monitoring

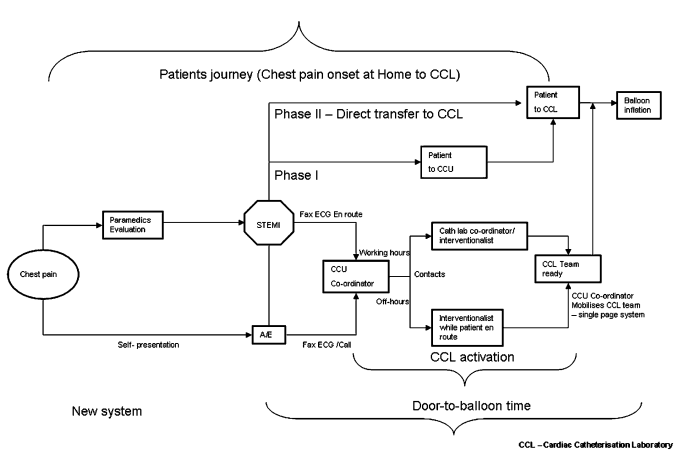

In their article, Kunadian et al. (2010) examine the issue of the data-monitoring system that allows receiving rapid feedback. They use Statistical Process Control (SPC) methodology to evaluate the outcome of the treatment in patients with the STEMI. The data included 841 participants in North England. The scholars assessed the median of D2B intervals. The following scheme helps to understand the results of the study better (Figure 3).

The investigation was divided into two phases. The first one consists of a coordinator nurse who realized the contact with the emergency crew and studies the history of the patient, who is on the way to the hospital. The second phase assumed to transfer the patient directly to the catheterization laboratory. After providing the statistical analysis, Kunadian et al. (2010) conclude that “SPC allows easy identification of significant outliers for investigation of any variation with a special cause. Data feedback and analysis allow planned changes in service delivery to be quantified” (p. 1562). Besides, Lin et al. (2010) also confirm the significance of the data feedback claiming that “by providing timely and valid data, the staff had the opportunity to increase attention to the quality of care and to seek for methods to improve performance” (p. 29).

Thus, one can note the effectiveness of the described method along with its relevance. It should be mentioned that the change project does not focus on SPC. Although, the quantitative data represented by means of the Chi-square and the Mann-Whitney U tests contribute to the appropriate analysis of the data. At the same time, the change plan might be affected by SPC methodology in order to deepen, detail, and visualize the investigation.

Same Page Strategy

Additionally, Kontos et al. (2011) state that the activation of the catheterization laboratory (CCL) via the same page strategy might reduce the D2B from 77 to 64 minutes. In particular, 295 patients took part in the research and were divided into four groups according to their clinical symptoms. As a result, the best outcome was achieved in the primary PCI with CCL. The study points out a gap in the change project.

D2B Reduction Necessity

Among other trends in D2B times in the STEMI patients, one might note the research by Pan et al. (2013) that concerns the evaluation of D2B intervals before and after the intervention. The study implemented such specific strategies as electrocardiography during triage for patients with chest pain, the Computerized Provider Order Entry (CPOE), and monthly meetings to review the STEMI patients’ registry. All in all, Pan et al. (2013) decreased the time of the D2B from 83 to 63 minutes.

Consequently, the above research reflects the same trend of the D2B reduction necessity as the change project. In addition, it applies the same strategies to achieve the desired outcome.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it should be stressed that the paper reflects the analysis of trends and gaps of the change project. It was revealed that there are such trends as the necessity to reduce the D2B in the STEMI patients and the use of computer or phone direct communication and staff training to realize it. Among gaps, there are gender and age differentiation, the same page strategy, and feedback monitoring.

However, in a bid to uncover all the issues and apply all the methods, it is impossible to initiate one research as it might be redundant and uninteresting for the reader. Instead, it seems that the best way to eliminate potential gaps is to conduct a series of research that would cover several peculiarities.

References

Chieffo, A., Buchanan, G., Mauri, F., Mehilli, J., Vaquerizo, B., Moynagh, A.,… Morice, M. (2012). ACS and STEMI treatment: Gender-related issues. EuroIntervention, 8(1), 27-35.

Kontos, M. C., Kurz, M. C., Roberts, C. S., Joyner, S. E., Kreisa, L., Ornato, J. P., & Vetrovec, G. W. (2011). Emergency physician–initiated cath lab activation reduces door to balloon times in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 29(8), 868-874.

Kunadian, B., Morley, R., Roberts, A. P., Adam, Z., Twomey, D., Hall, J. A.,… Belder, M. A. (2010). Impact of implementation of evidence-based strategies to reduce door-to-balloon time in patients presenting with STEMI: Continuous data analysis and feedback using a statistical process control plot. Heart, 96(19), 1557-1563.

Lin, J., Hsu, S., Wu, S., Liau, C., Chang, H., Liu, C.,… Ko, Y. (2010). Data feedback reduces door-to-balloon time in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart and Vessels Heart Vessels, 26(1), 25-30.

Pan, M., Chen, S., Chen, C., Chen, W., Chang, C., Lin, C.,… Chen, Y. (2013). Implementation of multiple strategies for an improved door-to-balloon time in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Heart and Vessels Heart Vessels, 29(2), 142-148.

Rathore, S. S., Curtis, J. P., Chen, J., Wang, Y., Nallamothu, B. K., Epstein, A. J., & Krumholz, H. M. (2010). Association of door-to-balloon time and mortality in patients admitted to hospital with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: national cohort study. BMJ, 338(2), 1-7.