Health Issue Identification and Non-Pharmacological Interventions

The clinical problem to be treated is traveler’s diarrhea (TD) (the case about Marco) that manifests itself in loose stools, fever, bloating, malaise, etc. as a result of stomach infection caused by contamination. It can be observed in people who travel outside their country or in other climatic geographic zones, in particular, tourists. In the pathogenesis of TD, there are four mechanisms, including intestinal secretion, increased osmotic pressure in the intestinal cavity, violation of transit of intestinal contents, and intestinal exudation. The key clinical goals are to prevent dehydration and achieve the antiperistaltic effect to treat the patient. It is possible to recommend such non-pharmacological interventions as a high intake of water to replace fluid losses, avoidance of coffee and dairy products that may worsen the situation, and focus on safe foods and beverages.

Clinical Practice and Pharmacological Interventions

Considering the clinical practice, one may note that loperamide reduces the tone and motor function of the intestine due to binding to its opioid receptors and an antidiarrheal effect. Conducting a prospective cohort study regarding the Department of Defense beneficiaries who travel outside the US, Lalani et al. (2015) discovered that loperamide in combination with antibiotics significantly reduces the symptoms of TD. The evidence of the above article is rather strong and credible: sample size is 1120 respondents, and clinical trials provided.

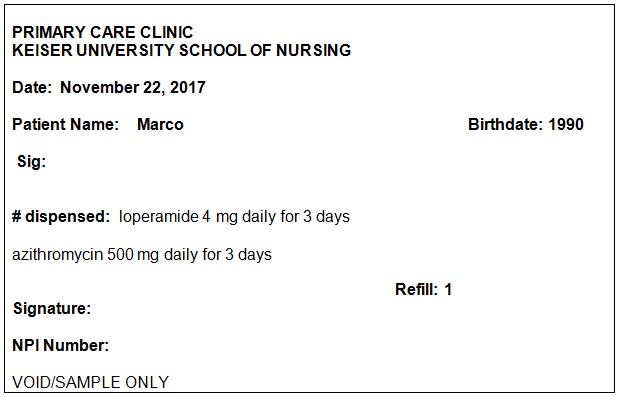

Another treatment option refers to the use of antibiotics as an early self-treatment. Giddings, Stevens, and Leung (2016) propose the prescription of azithromycin, an antibiotic of macrolide group that suppresses RNA-dependent protein synthesis of sensitive microorganisms and is active against most gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. According to Lalani et al. (2015), azithromycin is suitable for adults of any sex. Rao et al. (2014) emphasize that in the case of cardiac health problems, the intake of azithromycin may lead to the risk of cardiac arrhythmia and death. Azithromycin is quite stable at different pH values. After taking a single dose, more than 37 percent of azithromycin is absorbed in the stomach, and the average value of T1 /2 of azithromycin is 2-4 days. Azithromycin is to be prescribed 500 mg daily for three days (see Figure 1 for details). The selected option is more relevant than other medications such as ciprofloxacin or rifaximin in terms of cost, effectiveness, and side effects. The average cost of azithromycin is $25.32 – $46.71 for three days (Giddings et al., 2016). It is not available at Walmart and Target for lower prices.

The efficacy of the prescription is to be monitored during the patient’s visits and examination regarding his state of health and analysis. Any side effects occurring in the course of the treatment area to be reported by the patient and addressed accordingly with the help of non-pharmacological and, if necessary, pharmacological means. The drug-drug interaction is the effectiveness of loperamide and azithromycin taken together, while drug-food interaction refers to the consumption of water and loperamide as well as avoidance of dairy products and coffee. Patient teaching should consist of the following points:

- Do not exceed the prescribed dose;

- Report about any changes, side effects, and comorbidity promptly;

- Remember that impaired reactions or thinking may occur during treatment.

As for the preventative measures the patient may apply in the future, it is possible to recommend avoiding unsafe and potentially contaminated foods and beverages, properly washing heads before eating, and being cautious while using tap water. Pharmacological prevention includes vaccination and probiotics.

References

Giddings, S. L., Stevens, A. M., & Leung, D. T. (2016). Traveler’s diarrhea. The Medical Clinics of North America, 100(2), 317-330.

Lalani, T., Maguire, J. D., Grant, E. M., Fraser, J., Ganesan, A., Johnson, M. D.,… IDCRP TravMil Study Group. (2014). Epidemiology and self‐treatment of travelers’ diarrhea in a large, prospective cohort of department of defense beneficiaries. Journal of Travel Medicine, 22(3), 152-160.

Rao, G. A., Mann, J. R., Shoaibi, A., Bennett, C. L., Nahhas, G., Sutton, S. S.,… Strayer, S. M. (2014). Azithromycin and levofloxacin use and increased risk of cardiac arrhythmia and death. The Annals of Family Medicine, 12(2), 121-127.