Introduction

Aspden et al. (2004), in their 2003 Institute of Medicine of the National Academies patient safety report described electronic medical records as a system which encompasses, “a longitudinal collection of electronic health information for and about persons which can be immediately accessed by people with the help of an authorized user and can help in provision of knowledge and decision-support aimed at enhancing the quality, safety & efficiency of patient care and support for efficient processes for health care delivery”1. The objective of this is to assess the effect of automated screening of a patient’s electronic medical records on the quality of healthcare delivery and the cost of medical testing services.

Hypothesis

The study hypothesis is that automated screening of outpatient’s electronic medical records in various clinics in Midwestern USA increases the quality of care in patients with chronic illnesses while reducing the cost of their medical testing by 40% within a period of one year.

Literature Review

The Institute of Medicine, Deloitte research and other research firms have indicated that, despite health care being an information intensive industry, it remains highly fragmented and inefficient in comparison to the other sectors, such as banking, insurance and education. Nevertheless, major changes intended to reform the health care digital information systems have started to take centre stage2. These changes are aimed at considerably reducing the health care costs and increasing concerns for patient’s safety and the quality of health care3. Use of information technology to address improvements in patient safety is currently driving health care organizations to automate clinical care operations and associated administrative functions4.

Research findings published in the MEDLINE database from the Journal of American Board of Family Practice by Wilbur, Huffman, Lofto and Finnell in the year 2011, found that, “of the 8,489 emergency department patients who participated in the study, 5,794 (68.3%) of them were identified to be eligible for screening”5. Research also found that, “of the 1,484 (25.6%) patients approached for screening, 1,121 (75.5%) consented to be screened for HIV Virus and 5 (0.4%) received confirmed positive results”6. Research also revealed that, “the reasons for ineligibility, as determined by the electronic medical record system, were previous screening 1,125 (41.7%), age 890 (33.0%), known HIV 111 (4.1%) and those with unknown reasons were 569 (21.1%)”7.

It was concluded that, “clinical informatics solutions can provide automated delineation of emergency departments subpopulations eligible for HIV screening, according to predetermined criteria, which could increase program efficiency and might accelerate integration of HIV screening into clinical practice”8.

Research done by Liljeqvist et al. (2011) indicated that, “syndrome influenza-like illness data can be extracted automatically from routine general practitioners data and that how influenza-like illness trends in sentinel general practice compares with influenza-like illness trends in emergency departments has to be monitored using electronic medical records9”. This research indicated that, “the general practice surveillance tool identified seasonal trends in influenza-like illness both retrospectively and in real-time”10. The number of weekly influenza-like illness presentations ranged from 8 to 128 at general practice sites and from 0 to 18 in emergency departments in non-pandemic years11.

It was concluded that, “Automated data extraction from routine general practice records offers a means to gather data without introducing any additional work for the practitioner”12. Therefore, adding this method to current surveillance programs will enhance their ability to monitor influenza-like illness to detect early warning signals of new influenza-like illness events in the population13.

Ebbing, Woeltje & Malani (2010) asserted that, “individual components of an automated screening system could identify Surgical Site Infection Surveillance”. Peterson et al. indicated that, “the use of coded diagnoses, tests, and treatments in the medication record had a sensitivity of about 74% and that specific codes and combinations of codes identified a subset of 2% of all procedures, among which 74% of Surgical Site Infection Surveillance occurred and that the use of hospital discharge diagnosis codes and pharmacy dispensing data had a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 94%”14.

In other research conducted by Platt and his associates, it was indicated that “automated claims and pharmacy data from several health insurance plans can be combined to allow routine monitoring for indicators of postoperative infections” 15.

Buuam demonstrated that, “cooperation between infection control and medical informatics personnel can produce an automated system of surveillance which requires much less time and performed well with sensitivity and a specificity of 91%16. In research, to determine if automation of patients’ electronic records improve surrogate patient’s outcomes in outpatient settings done by Anthony Jerant and David Hill, it was indicated that, “utilization of either complete or hybrid Electronic Medical Records can improve some surrogate outpatient’s care outcomes”17.

Methodology

In order to collect rational data, simple random sampling methods will be employed. 250 diabetic terminally ill patients who will have attended clinics for at least one year will be used as a sample population for the study. The respondents and the medical clinics who will participate in the study will be selected randomly from the Midwest region of USA18. Two physicians from each of the ten selected clinics will be selected as key respondents to give first hand information on how the automated screening of outpatient electronic medical records for terminally ill patients affects the care and cost of medication of those patients19.

The physicians will be required to use their own discretion, based on their experience, to determine whether care and cost of medication has been impacted on. Data collection from the 250 diabetic terminally ill patients who will have been selected using simple random sampling methodology will be done by five research assistants who will interview 50 patients each.

Smith will be the project manager of the exercise. He will be responsible for planning, organizing, staffing, directing, controlling, reporting and budgeting. The project will be one year in duration.

Time Line

- Week1- 2: seek legal permission from research governing bodies.

- Week 3 -7: send structured questionnaire to the key respondents.

- Week 8 – 40: conduct interviews from the 250 diabetic terminally ill respondents.

- Week 41 -45: data analysis and reporting of the research findings.

- Week 46-47: Begin preparing paper for submission to the Journal articles.

- Week 48: Submit journal article for publication.

- Week 49-52: Submit report to the government medical agency that provides the grants.

Personnel

Patel will be the principle investigator. He has 5 years experience as a statistician with knowledge in data collection and analysis. He will be in charge of the research team and will supervise them and ensure that the process is going according to the regulations governing social scientific research. He will be totally committed to the process from initiation to the reporting cycle of the project. The principle investigator will send the structured questionnaires to the selected key respondents. The principle investigator will train the research assistants for a period of 5 days and also supervise them during data collection for a period of 5 days. The principle investigator will also conduct data storage, analysis and reporting.

The research assistants will have 2 years experience in research work. They will work under the principal investigator and each will be assigned specific tasks. They will interview 250 of the selected diabetic terminally ill respondents mentioned above. The research assistants will be part of the process during the data collection phase and will be trained by the principal investigators for 3 days, on how to use data collection tools, such as interview questionnaires.

The project will also engage the services of a clerical staff person (Hansen) who will be experienced in general clerical work, and provide 10 percent of the project time. His responsibility will be to keep an inventory of the logistics and costs associated with the project in order to ensure transparency and accountability of expenditures.

Data Collection and Storage

Questionnaires will be mailed to the 20 selected physician homes. Pre-addressed and postage-paid return envelopes will be provided. Follow-up mailing will be done to their offices 2 weeks later. The reminders will be conveyed via email, weekly newsletters and staff meetings. Information from the 20 key respondents will be expected after 5 weeks from the time the first mailing process is done20.

The ten selected medical clinics will be contacted and booked for the exercise. The clinic’s management will be requested to allow the research team to interview 25 terminally ill patients from each of the ten selected clinics who meet the condition that, ‘the respondent must have attended the clinic for at least one year’21. Five research assistants will collect data from fifty respondents for at least ten hours a day for a period of five days.

The data will be stored on a personal computer and later on analyzed using SPSS Version 11.0.1 software22. To safeguard security of the data, a comprehensive data security system, complete with passwords will be implemented. Only the authorized persons will have access to the passwords to ensure confidentiality. Those who will have access to the information are only the members of the research team. After the mission is accomplished, all the data will be destroyed.

Data Analysis and Evaluation

Data will be analyzed appropriately using SPSS software. This will be based on the category of responses from the various respondents23. The data will later be cross examined with the medical clinics reports data. The findings of the study will form part of the final research study report, and will be disseminated to the study respondents and also to medical data bases such as MEDLAB in order to be used in decision making and policy making24. The results of the project will also be disseminated through journal articles in journal of medical science, with the intention of targeting different medical professionals so they can gain some insights on its findings and recommendations.

References

- Aspden, P., Corrigan, J., Wolcott, J., & Shari, M. (2004). Patient safety: Achieving a new standard for care, Committee on data standards for patient safety and board on health care services. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- United States general Accounting office. (2003). Information technology benefits realized for selected health care functions. USA: Diane publishing company.

- Wilbur, L., Huffman, G., Lofto, S., & Finnell, J. (2011). The use of a computer reminder system in an emergency department universal HIV screening program. Annals of emergency medicine, 58(1), 71-73.

- Liljeqvist, G., Staff, M., Puech, M., Blom, H., & Torvaldsen, S. (2011). Automated data extraction from general practice records in an Australian setting: trends in influenza-like illness in sentinel general practices and emergency departments. BMC Public health journal, 6, 11:435.

- Peterson, L., Hacek, D., Rolland, D. and Brossette, S. (2003). Detection of a community infection outbreak with surveillance. Lancet, 362(1), 1587-1588.

- Goatham, J., Smith, F., Birkhead, S., & Daisson, C. (2003). Policy issues in developing information systems for public health surveillance of communicable diseases. New York: Springer publishers.

- Jerant, A., & Hill, D. (2000). Does the Use of Electronic Medical Records Improve Surrogate Patient Outcomes in Outpatient Settings? The journal of family practice, 49(4), 349-357.

- Immy, H. & Wheeler, S. (2010). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Vogt, P. (2010). Data collection. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Griffith, A. (2010). SPSS. Hoboken : John Wiley & Sons.

- Lee, T., & Wang, J. (2003). Statistical methods for survival data analysis. New York: Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley.

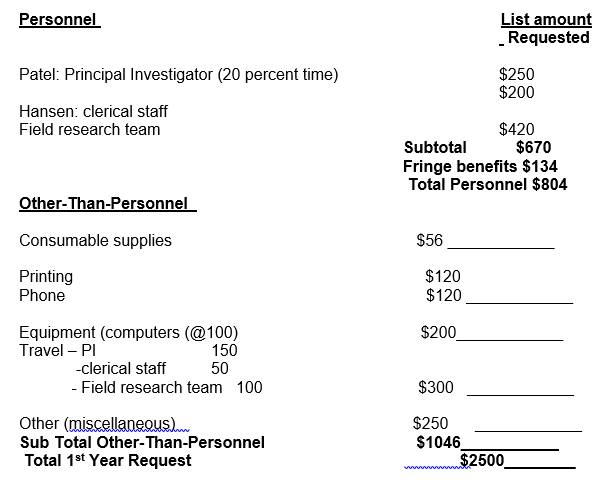

Year One Budget

Budget Justification

- Patel: Principal Investigator –this is to fund all the expenses that he incurs in the course of the project, as well as his salaries.

- Hansen: clerical staff- this is to fund all the expenses that he incurs in the course of the project, as well as his salaries.

- Field research team – this is to fund all the expenses that they incur in the course of the project, as well as their salaries.

- Consumable supplies – this will cater for food and beverages of the personnel during the course of the project.

- Printing – this fund will be spent on printing of the projects documents Phone- spent on airtime and handsets for all the staff.

- Equipment (computers) – the money will be spent on purchasing this computers which is required for data storage and analysis.

- Travel – this will cater to money spent on transport in the course of discharging the project, by any of the personnel.

- Other (miscellaneous) – this may cater for any other expenses such as stationery.

Questionnaire

- Does the electronic records system contain all the important information of patients, from the time they are admitted until they are discharged?

- Is the stored information readily available or accessible by the physicians attending the patient?

- Does the system keep record for all the patients, including inpatients, outpatients, emergency and accidents patients?

- Is there a particular identification criterion for different categories of patients, such as national identity? If there is no particular identification number, what information is used to identify each patient?

- Does the institution use computerized Patient Master Index (PMI)?

- Does the institution undertake a proper documentation of all medical record?

- What is the quality of the medical records?

- Are the daily discharge and admission statistics list produced?

- Does the medical records staff collect and compile the inpatient morbidity statistics?

- Is there any complication due to duplication of medical records?

- Is any delay experienced in the completion of reports?

- Does the increased efficiency as a result of use of electronic medical records system decrease costs in the long-term?

Footnotes

- (Aspden, Corrigan, Wolcott & Shari, 2004).

- (United States general Accounting office, 2003).

- (United States general Accounting office, 2003).

- (United States general Accounting office, 2003).

- (Wilbur, L., Huffman, G., Lofto, S. & Finnell, J., 2011).

- (Wilbur, L., Huffman, G., Lofto, S. & Finnell, J., 2011).

- (Wilbur, L., Huffman, G., Lofto, S. & Finnell, J., 2011).

- (Wilbur, L., Huffman, G., Lofto, S. & Finnell, J., 2011).

- (Liljeqvist, Staff, Puech, Blom & Torvaldsen, 2011).

- (Liljeqvist, Staff, Puech, Blom & Torvaldsen, 2011).

- (Liljeqvist, Staff, Puech, Blom & Torvaldsen, 2011).

- (Liljeqvist, Staff, Puech, Blom & Torvaldsen, 2011).

- (Liljeqvist, Staff, Puech, Blom & Torvaldsen, 2011).

- (Peterson, Hacek, Rolland & Brossette, 2003).

- (Goatham, Smith, Birkhead, & Daisson, 2003).

- (Goatham, Smith, Birkhead, & Daisson, 2003).

- (Jerant & Hill, 2000).

- (Immy, & Wheeler, 2010).

- (Teddlie &Tashakkori, 2009).

- (Vogt, 2010).

- (Vogt, 2010).

- (Griffith, 2010).

- (Lee & Wang, 2003).

- (Lee & Wang, 2003).