Introduction

Nurses’ continuous training is essential for modern hospitals and healthcare professionals (Dyson, Hedgecock, Tomkins, & Cooke, 2009; Mill, Astle, Ogilvie, & Gastaldo, 2010). One of the main factors that contribute to this requirement is the exceptionally fast pace of the nursing theory and practice development, which doubles the amount of nursing-relevant information every five years (Keogh, Fourie, Watson, & Gay, 2010). For nurses, it is imperative to refresh and acquire knowledge and skills through continuous learning and training (Turner, Davies, Beattie, Vickerstaff, & Wilkinson, 2006); in part, it is also a moral obligation (Karseth, 2004).

In this research, an educational needs assessment (ENA) is carried out for Emergency Unit nurses working at the King Saud General Hospital in Alqassem City. An educational (learning) need (EN) can be defined the difference (gap) between a personal level of knowledge and the desired one that can be stated personally, required by the employer, believed to be necessary for the society, and so on (DeSilets, 2007). Defining ENs is essential for the improvement of continued learning efficiency. In this paper, the results of ENA will prepare the basis for the development of an education program that will be meant to satisfy the specific ENs of the Emergency Unit nurses.

The present paper includes the background and theoretical information required for the study, describes its data collection methods, analyses the data, offers an education program plan, summarises the findings, and draws conclusions that will be used in the future. The paper does not include all of the results: only the most important or interesting data and findings are presented to avoid excessive details.

Background

King Saud Hospital is a modern institution that strives to incorporate the newest technological and scientific achievements, which makes the continuous education of nurses an essential requirement for its success. To ensure the effectiveness of continued training, it is necessary to carry out ENA systematically. ENA eliminates bias, informs planning (DeSilets, 2006), and allows more effective learning (when compared to ad hoc course development), which ensures adequate spending of the resources (finances, time, efforts) that are allocated to education (Dyson et al., 2009). Apart from that, due to the changes in practice and environment, ENs also develop (Turner et al., 2006). As a result, it is recommended to start the majority of training activities with an ENA to determine the knowledge gaps of the target group (DeSilets, 2006; Forbes, While, & Ullman, 2006).

Data Collection Methods

Sample

The presented research involves surveying King Saud General Hospital Emergency Unit nurses. The initial sample included 22 nurses. The Hospital and the Unit were chosen as the workplace of the researcher; I am familiar with the specifics of the work in the Unit, which facilitated the process of the tool and plan development.

In particular, this experience helped me to determine the potential knowledge gaps based on the skills and expertise that are typically employed by an Emergency Unit nurse, which is a common practice in ENA development (Dyson et al., 2009). My assumptions were later supported by the results of an informal brainstorming carried out among seven nurses of the Unit, which is also a viable technique of ENA (DeSilets, 2007). These activities helped me to determine the three topics that were later offered for the nurses to rank.

Also, the experience allows me to make assumptions concerning the possible outcomes of the present survey. I presume that medication errors and drug calculation are likely to be considered most essential since the former are the most commonly encountered errors (Fleming, Brady, & Malone, 2014) while the latter involves calculation skills that nurses often perceive as difficult (Sneck, Saarnio, Isola, & Boigu, 2016).

Tool: Development, Validity, and Structure

While it is possible to introduce objective elements into an ENA (Forbes et al., 2006), it is typical to base ENA on subjective data from surveys and questionnaires (DeSilets, 2007; Dyson et al., 2009). Questionnaires are a commonly used data collection tool, the development of which requires a “logical, systematic and structured approach” (Rattray & Jones, 2007, p. 234).

It is best to use a validated, approved questionnaire, but it is not always an option (Timmins, 2015). Given the fact that the search for a suitable ENA questionnaire for Emergency Units was unsuccessful, a data collection tool had to be developed. To ensure its validity, it was created in collaboration with Department of Training and Education at King Saud General Hospital with the help of a literature review on ENA tools development, the majority of which is referenced in this paper. Also, a pilot pre-test was carried out to receive the feedback concerning the presence of redundancies and relevance of the individual items to ensure that the questionnaire “measures what it says it measures,” which means that it is valid (Timmins, 2015, p. 45).

The final version of the tool is a multipart questionnaire that includes a demographic data section, Likert scale ENA, ENs specification section with open questions, and learning preferences section with multiple-choice and open questions (see Appendix A). To sum up, the questionnaire collects quantitative (Likert scale) and qualitative (other parts) data, which turns the presented research into a mixed-method one. The use of the items of various types allows combining their respective advantages: for instance, Likert scale data is easier to analyse, but open-ended questions provide more information (Rattray & Jones, 2007).

The demographic data was collected to suggest a possibility of tracking the relationship between the experience and qualifications of a nurse and their choice of topics. The key part (ENA) was designed to produce two types of score. First, we wanted to determine the most essential (ME) score, which is defined by the number of respondents who consider a topic to be most essential. Second, the total score was determined with the help of the Likert scale were a “most essential” option scores three points, an “essential” one scores two, and a “least essential” one scores one (Barua, 2013).

The ENs specification part was meant to discover the motivation behind the nurses’ choices, and the final learning preferences section was created to define preferred activities and aids to facilitate the development of the education plan. There is a natural limitation to the tool: the self-awareness of the respondents may vary, and their assessment of ENs may be wrong, but in this case, their choices may be considered their “perceived” ENs, which are also important to satisfy (Dyson et al., 2009).

Tool Implementation and Related Difficulties

The tool was distributed in its printed version at the workplace. This strategy was chosen because the number of nurses was limited, which reduced the expenses of printing the questionnaires, and because it was easy to reach them personally. Nurses were also offered to use the electronic questionnaire, but 100% of them chose to fill out printed documents. The diversity of formats was proposed to make the process of filling out the questionnaires as convenient as possible, and it can be suggested that this aim was achieved. Nine questionnaires were filled by the nurses on the spot; thirteen questionnaires were taken home, and nine of them were returned.

The implementation process demonstrates that the questionnaire was mostly successful, and its print variant suited the ENs of the respondents. One respondent, however, had difficulty in fitting the answers in the third section, which indicates a limitation of the use of a printed questionnaire. In other words, a printed questionnaire has a limited amount of space, and some respondents may find this aspect restrictive.

Also, the differences in handwriting may further restrict some of the users of a paper questionnaire. Unfortunately, the pilot test did not reveal this issue, and it could not be fixed beforehand. It is also noteworthy that online questionnaires may have similar limitations and that the restrictions in the word count of a response help to reduce the amount of data to be analysed, which is why the issue can be regarded as a necessary step in certain cases.

Three of the respondents added comments to the second section, apparently finding the task of ranking the topics controversial and attempting to explain their choice. Two of them insisted that they could not rank the topics. During the pre-test, no similar difficulties were encountered. Together with the Department of Training and Education we considered the issue and surmised that a more extensive Likert scale (for example, with ten points from “less essential” to “most essential”) could remove the need to rank and offer more options while slightly increasing the complexity of the data analysis.

Data Analysis

22 questionnaires were handed out, and 18 questionnaires were returned, which means that the response rate of the survey was 81%. Such a response rate is considered to be very successful; for the majority of purposes, the rate of 60% would suffice (Fincham, 2008). The demographics of the nurses can be summarised in the following way. All the nurses had at least two years’ experience in an Emergency Department with four (22%) nurses having this minimum experience; 8 nurses (45%) had over five years of experience in the area, and two (11%) had nine years of experience, the remaining nurses having between two and five years of experience. Only one nurse (5.5%) worked at the King Saud General Hospital for less than two years. The ages of the respondents varied from 24 to 46 years.

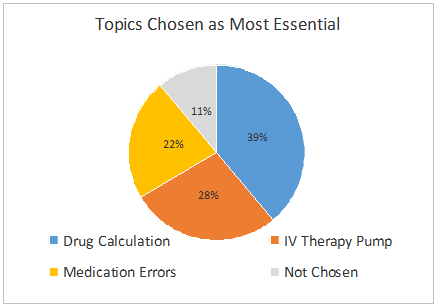

Every topic was chosen as the ME by at least four respondents (medication errors); IV therapy pump was selected by five respondents, and the drug calculation was highlighted by seven respondents. None of the nurses considers drug calculation to be the least important topic, and both the least and one of the most experienced nurses chose it as the most important topic. The total score corresponded to ME. Two nurses stated that choosing the most important topic was too difficult for them, and their answers were placed in the “not answered” category. The results of the survey can be viewed in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Findings

Both the total and ME score demonstrate that the most urgent EN of the Emergency Unit nurses at King Saud Hospital is drug calculation followed by IV therapy pump and medication errors. Drug calculation was chosen by nurses regardless of their qualifications and experience, which implies that the topic is indeed most essential for the Hospital Emergency Unit nurses.

The third part revealed that the drug calculation topic is considered to be difficult by 13 nurses (72%) because they feel insecure about their calculation skills. Thus, my initial assumptions were confirmed to an extent and partially proven wrong as I ranked medication errors to be more significant than the IV pump. This case shows that ENA is more reliable than the assumptions of an educator, even if he or she is familiar with the students and the context (DeSilets, 2006).

The fourth section informed the choice of instructional techniques (see Table 2). 100% of nurses are interested in PowerPoint presentations while handouts were chosen by 16% of the nurses. Also, 66% of nurses consider group discussions to be useful, but games and interactive forms of learning did not receive much approval (22%).

PowerPoint presentations are very illustrative, highly visual, easy-to-use, and they can improve the motivation of students when used effectively (Nowak, Speakman, & Sayers, 2016), which is why the choice of the nurses is not surprising. The lack of the interest in games might seem surprising, but it may be suggested that the kinaesthetic style of learning does not appeal to the majority of the nurses from the Unit (Boctor, 2013).

The results of the survey were used to design the education plan that is exhibited in Table 2. The plan is meant for a four-week program, and it includes all the topics since all of them received an ME score, but the amount of time and activities that are allocated to a particular topic depending on its total and ME score. Drug calculation is the primary part of the program; the topic is most important for patients’ safety as errors in calculations may lead to gravest results (Wright, 2013). However, this area of practice is also interdisciplinary: it requires mathematical skills (Coben & Weeks, 2014).

It was discovered that it is typical for nurses to experience more difficulties with calculation skills than related theory (Sneck et al., 2016), but the lack of the theory is as harmful to practice as the lack of the skill (Fleming et al., 2014). IV therapy is the second EN for its urgency; it presupposes the infusion of therapy-defined substances intravenously. The related theory and practice are of supreme importance for a nurse, and training in this area helps to ensure the safety of the patients (Dougherty, Kayley, & Bravery, 2012).

Medication errors were defined as the third urgent EN; this topic is devoted to a preventable but persistent issue that proceeds to plague nurses worldwide despite the advances in theory and practice (Leufer & Cleary-Holdforth, 2013). The topic is also multidisciplinary, and the factors that contribute to the issue range from the lack of attention to inadequate safety regulations; additional training can help to improve the situation in a particular unit (Jones, 2009).

The presented plan dwells primarily on the content, activities, and assessment methods, which does not cover all the five elements of a curriculum item (Prideaux, 2007), but it still offers a succinct representation of the intervention. It may also be mentioned that the aim of this plan consists in addressing the specific needs of the Emergency Unit nurses, and the expected outcomes include the improvement of the nurses’ objective and perceived competencies in the areas and the increase of their self-confidence.

Conclusion

The presented paper provides a summary of an ENA survey that was meant for Emergency Unit nurses who work at the King Saud Hospital in Alqassem City. The research employed a customised tool, the validity of which was tested in collaboration with the Hospital’s Department of Training and Education. The results demonstrated that the nurses believe the drug calculation to be the most essential topic; it is followed by IV therapy pump and medication errors. Apart from the knowledge gaps, the ENA helped to determine the prevailing educational preferences of the nurses.

Finally, the research showed that the researcher was not able to completely predict the results of the survey, which demonstrates the importance of ENA for productive teaching and learning. The results of the survey will be used to design an effective educational program for the Unit nurses, which will ensure that they are provided with the training that they need in a form that will suit their learning preferences and which will guarantee that the educational resources are employed efficiently.

References

Barua, A. (2013). Methods for decision-making in survey questionnaires based on Likert scale. Journal of Asian Scientific Research, 3(1), 35.

Boctor, L. (2013). Active-learning strategies: The use of a game to reinforce learning in nursing education. A case study. Nurse Education in Practice,13(2), 96-100. Web.

Coben, D., & Weeks, K. (2014). Meeting the mathematical demands of the safety-critical workplace: medication dosage calculation problem-solving for nursing. Educational Studies In Mathematics, 86(2), 253-270. Web.

DeSilets, L. (2006). Needs Assessment. Journal Of Continuing Education In Nursing, 37(4), 148-149. Web.

DeSilets, L. (2007). Needs Assessments: An Array of Possibilities. Journal Of Continuing Education In Nursing, 38(3), 107-112. Web.

Dougherty, L., Kayley, J., & Bravery, K. (2012). IV therapy: get it right no matter what. British Journal of Nursing, 21(Sup14), S3-S3.

Dyson, L., Hedgecock, B., Tomkins, S., & Cooke, G. (2009). Learning needs assessment for registered nurses in two large acute care hospitals in Urban New Zealand. Nurse Education Today, 29(8), 821-828. Web.

Fincham, J. E. (2008). Response Rates and Responsiveness for Surveys, Standards, and the Journal. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(2), 43. Web.

Fleming, S., Brady, A., & Malone, A. (2014). An evaluation of the drug calculation skills of registered nurses. Nurse Education in Practice, 14(1), 55-61. Web.

Forbes, A., While, A., & Ullman, R. (2006). Learning needs analysis: The development of a tool to support the on-going professional development of multiple sclerosis specialist nurses. Nurse Education Today, 26(1), 78-86. Web.

Jones, S. W. (2009). Reducing medication administration errors in nursing practice. Nursing Standard (through 2013), 23(50), 40-6. Web.

Karseth, B. (2004). Curriculum changes and moral issues in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 24(8), 638-643. Web.

Keogh, J., Fourie, W., Watson, S., & Gay, H. (2010). Involving the stakeholders in the curriculum process: A recipe for success?. Nurse Education Today, 30(1), 37-43. Web.

Leufer, T., & Cleary-Holdforth, J. (2013). Let’s do no harm: Medication errors in nursing: Part 1. Nurse Education in Practice, 13(3), 213-6. Web.

Mill, J., Astle, B., Ogilvie, L., & Gastaldo, D. (2010). Linking Global Citizenship, Undergraduate Nursing Education, and Professional Nursing. Advances In Nursing Science, 33(3), E1-E11. Web.

Nowak, M. K., Speakman, E., & Sayers, P. (2016). Evaluating PowerPoint presentations: A retrospective study examining educational barriers and strategies. Nursing Education Perspectives, 37(1), 28-31.

Prideaux, D. (2007). Curriculum development in medical education: From acronyms to dynamism. Teaching And Teacher Education, 23(3), 294-302. Web.

Rattray, J. & Jones, M. (2007). Essential elements of questionnaire design and development. Issues In Clinical Nursing, 16(2), 234-243. Web.

Sneck, S., Saarnio, R., Isola, A., & Boigu, R. (2016). Medication competency of nurses according to theoretical and drug calculation online exams: A descriptive correlational study. Nurse Education Today, 36, 195-201. Web.

Timmins, F. (2015). Surveys and questionnaires in nursing research. Nursing Standard, 29(42), 42-50. Web.

Turner, C., Davies, E., Beattie, H., Vickerstaff, J., & Wilkinson, G. (2006). Developing an innovative undergraduate curriculum – responding to the 2002 National Review of Nursing Education in Australia. Collegian, 13(2), 7-14.

Wright, K. (2013). How do nurses solve drug calculation problems? Nurse Education Today, 33(5), 450-457. Web.