Abstract

Depression, which is a major concern in the United States, is important to diagnose early for improved patient outcomes. However, depression screening in primary care has been lacking; its rates do not exceed 5%, and they are especially low for particular groups. Moreover, with certain populations, depression screening is more complicated. Those populations include geriatric patients, who run increased risks of depression with age.

The purpose of the presented DNP project consisted of carrying out a depression screening training in primary care with patient referrals before and after the training as the outcome. Two different tools (Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)) were used; PHQ-9 was employed before the training and GDS was applied after training. The sample included nine healthcare professionals, most of which (78%) had been familiar with at least one of the tools.

The findings showed that more people were referred after the training (42% as compared to 11%), but the collected data were incomplete because of the coronavirus. Indeed, only nine people completed PHQ-9, and GDS was completed by seven people only. No statistically significant differences were found as a result, and no conclusions about the effectiveness of the training or the differences or similarities between the two tools could be made. However, the results are generally in line with the information collected from the literature review, even though more research is required.

The main practical implication of the project is that primary care practitioners might demonstrate a lack of knowledge of the tools that are available for depression screening in the settings. However, both the literature review and the present project do not supply enough evidence to determine the effectiveness of the training and the usability of both tools, which is why additional studies are needed.

Introduction

Depression is an increasingly widespread issue in the United States (US). It is not treated in primary care, but it is screened for with the help of diverse tools, which can then lead to a mental health referral. One of the populations that are especially vulnerable when it comes to depression and especially difficult to diagnose with depression are older adults (Espinoza & Unützer, 2015; Zaccagnini & White, 2014).

There is little research about the effectiveness of different depression screening tools with this population, but some of the most commonly employed instruments include the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (Yesavage et al., 1982), as well as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Pfizer Inc., 1999). Additionally, one of the common issues in primary care is the lack of depression screening or training aimed at improving depression screening (Al-Qadhi, Rahman, Ferwana, & Abdulmajeed, 2014; American Psychiatric Association, 2017). In other words, depression is a serious condition that is difficult to diagnose in older patients, and healthcare providers are not always trained to do so.

In this report, a project dedicated to a training for the use of different tools in geriatric primary care depression screening is going to be described. The report involves an analysis of the existing evidence, an explanation of the specifics and significance of the current inquiry, and an overview of the methodology and outcomes of the project.

Clinical Problem

Depression is a major healthcare concern in the US and globally (American Psychiatric Association, 2017; Cohen & Edmondson, 2015; Farrer et al., 2016; Fekadu, Shibeshi, & Engindawork, 2017; Ferenchick, 2019; Thabet et al., 2020). It is a significant healthcare issue that is evidenced to be associated with reduced quality of life, negative outcomes (including suicidal behavior), and increased healthcare spending (Thabet et al., 2020).

Depression-related visits often (up to 50% of cases) occur in primary care settings (Ferenchick, 2019), but the majority of primary care patients (over 95%) are not screened for depression, which may be partially the cause of the low recognition and treatment of depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2017; Park & Unützer, 2011). At the same time, early recognition and treatment of depression are critical for health outcomes in patients (Conradsson et al., 2013). As a result, the problem of the lack of screening in primary care is rather acute.

It is also important that additional difficulties in diagnosis may be present for particular populations. For example, the prevalence of depression among older adults is significantly lower than it is among younger people, with 13.1% of the former population experiencing a major depressive episode in the past year, and only 4.7% of the latter population doing the same (National Institute of Mental Health, 2019).

However, older patients experience lower chances of accurate diagnosis because the symptoms of depression, for example, changes in information processing or eating habits, overlap with the natural age-related changes (Espinoza & Unützer, 2015; Zaccagnini & White, 2014). In other words, it is difficult to diagnose depression in older adults, which further highlights the importance of screening for this population.

However, other causes of depression mismanagement at the screening stage include managerial failures (Moriarty, Gilbody, McMillan, & Manea, 2015), as well as the lack of training in healthcare professionals (Al-Qadhi et al., 2014). Given that the difficulty in depression management which becomes prominent at the old age cannot be altered, the possibility of equipping primary care practitioners with the knowledge and other tools that can facilitate undertaking the challenge is crucial.

Finally, it should be noticed that some topics are understudied, and that includes training primary care practitioners in screening for depression in older populations (O’Connor et al., 2016). Thus, the clinical problem of this project is the underscreening for depression in primary care settings as attributable to the lack of training in practitioners, and it is a significant issue that has not been studied very extensively.

Significance

With around eight million cases in the US each year (Ferenchick, 2019), with up to 13% of the population affected by the disorder over their lifetime (American Psychiatric Association, 2017), depression is a significant, widespread concern. According to the American Psychiatric Association (2017), only about 5% of adults who visit primary care services are screened for depression, which leaves about half the cases unrecognized.

Older people are an especially challenging population in terms of depression screening (Espinoza & Unützer, 2015; Zaccagnini & White, 2014). Thus, the problem clearly affects a large portion of the population of the US, with patients with depression and their families being the primary stakeholders. Additionally, it is important to address gaps in literature (Polit & Beck, 2017), and the presented problem is such a gap (O’Connor et al., 2016).

Definition of Terms

Depression is a shortening of the diagnosis termed major depressive disorder (including major depressive episode). It is a mental health disorder that is characterized by depressed mood, diminished interest and pleasure, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, and some other diagnostic criteria that “cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning” and are “not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or to another medical condition” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Depression screening is the process of identifying disease (in this case, depression) in individuals (American Psychiatric Association, 2017). GDS and PHQ-9 (Pfizer Inc., 1999; Yesavage et al., 1982) are common tools employed to that end.

Older patients (geriatric population, the elderly): this term has varied definitions, but in this project, patients aged over 65 are considered geriatric patients.

Review of Evidence

In this section, the PICOT question is going to be developed and contextualized with the help of a review of the existing evidence.

PICOT Question

Among practitioners in primary care settings (P), is there any difference in the number of geriatric patients referred to mental health practitioners for evaluation for depression (O) as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-(PHQ-9) screening tool and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (C) as a result of training aimed at teaching practitioners to use both tools (I) over the course of six weeks (T)?

Search Method

The existing evidence pertaining to the PICOT topics (PHQ-9, DGS, depression, screening, and primary care) was collected by searching MEDLINE, Cochrane, CINAHL, and PubMed databases, which are the most common choices for modern healthcare-related research (Polit & Beck, 2017). Recent literature (not older than seven-eight years) was selected due to the same considerations. The specific search terms included “depression screening,” “depression screening training,” “GDS,” “PHQ-9,” “Geriatric Depression Scale,” “Patient Health Questionnaire-9,” “primary care,” “older people,” “geriatric,” “elderly.”

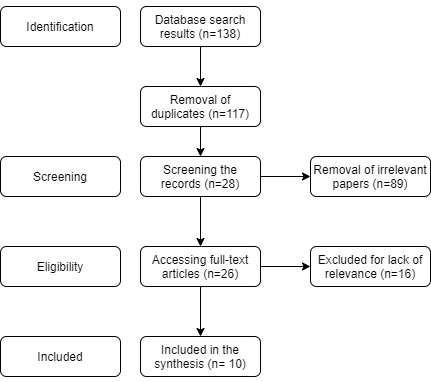

Logical operators were employed in the following way: the search involved looking for “depression screening” AND “primary care” AND (“older people” OR “geriatric” OR “elderly”). Upon looking through the abstract and then (if relevant) full-text articles, a total of 10 useful articles was identified.

The sources that did not include the specific depression scales that are being studied by the project but did incorporate helpful information about depression screening in geriatric populations in primary care were included, and the sources that did focus on the specific depression scales but did not incorporate some of the other search terms were included as well. Only peer-reviewed sources were employed, and only the English language was selected. The search in different databases yielded some similar results, which is why the elimination of duplicates was required; additionally, some of the literature was not relevant for the search. Figure 1 represents the search flow.

Search Results

The search resulted in a total of 10 relatively relevant articles, four of which were dedicated to the tools, and the rest of which discussed the various aspects of depression screening in primary care. The details of the five most relevant sources are presented in Appendix A; also, they are discussed in detail below.

Synthesis of the Evidence

Depression Screening

Depression is prevalent worldwide, but importantly, it is underdiagnosed (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Thabet et al., 2020). Depression rates in older adults are relatively low, but they grow with age, and depressive symptoms in older adults occur in 10-15% of the population (Kok & Reynolds, 2017). However, depression screening in recent research is indicated to be low. Akincigil and Matthews (2017) carried out a secondary analysis of a nationally representative (US) sample of over 33,000 physician-patient encounters.

The results suggested that the rate of screening for depression amounted to 4.2%, with African Americans and the elderly being less likely to be screened. Additionally, the providers who had adopted Electronic Health Records were more likely to employ depression screening, even though various financial incentives did not have an impact on that behavior. This type of quantitative study should be representative of the nation-wide situation, but it is not representative of individual regions.

However, the overall quality of the study is high, and it can be used to demonstrate that depression screening is not used very extensively in primary care. Importantly, the study also suggests that depression screening depends on some qualities of the provider, even though training is not mentioned here.

Regarding the benefits of depression screening, this topic has been researched well but not for the population of interest to this project. Thus, Pfoh et al. (2020) carried out a cohort study with more than 250,000 patients as the study population. The goal was to determine if the implementation of systematic screening could have any effect on patients diagnosed with depression receiving treatment. The findings suggested that it was the case.

Indeed, the number of patients receiving treatment within three months after diagnosing increased in a statistically significant way, and the odds of treatment increased by 20%. This article has limited generalizability, but its sample size is rather big, and the results can be used to argue the importance of depression screening in primary care.

In a similar way, Randle, Spurlock and Kelley (2019) focused on the effects of depression screening implementation in primary care. With a sample of 200 African American individuals, the research showed that after the implementation of the routine use of a specific standardized screening tool, the number of depression diagnoses increased by 41%. This study is not very generalizable, its sample is not very big, and it does not incorporate any outcomes other than the number of diagnoses, but it does show that the use of screening tools, especially standardized, can be helpful in primary care.

Rhee, Capistrant, Schommer, Hadsall and Uden (2017) carried out a study that was particularly relevant for the presently described project. The authors focused on primary care and older adults, highlighting the fact that the existing evidence provides rather conflicting information regarding the efficacy and effectiveness of screening for depression in those settings and that population. A nationally representative sample of outpatient visits (over 9,000) was employed to determine the effects of depression screening, including diagnosing depression, prescribing antidepressants and prescribing inappropriate medications.

The latter outcome was negatively associated with depression screening, and the rest of them were in no correlation with it. This finding is not exactly in line with other research, which suggests that depression diagnosing should increase as a result of increases in depression screening (Randle et al., 2019). Still, this article suggests that depression screening in primary care (aimed at the elderly population) can have positive outcomes, and even though it is a single study, its sample is very large and representative.

O’Connor et al. (2016) carried out a literature review (overview of evidence) with a very clear and systematic methodology to identify the benefits and harms of primary care depression screening in different populations. Specifically for older adults, only four trials were identified, and they did not suggest any positive outcomes of depression screening in that population. Furthermore, the overall evidence of health benefits associated with primary care depression screening was considered weak.

However, in some populations, particularly those that were better studied, some evidence of positive health outcomes was identified. The study is very high-quality, and the level of evidence for a systematic review of trials is the highest (Polit & Beck, 2017). As a result, the presented article suggests that the topic is not very well-studied, and more research on the specific population chosen for this project is required.

To summarize, the research on the topic of depression screening among older adults in primary care is not very extensive. The existing evidence can suggest that older adults are less likely to be screened, even though they might benefit from the practice. Additionally, the research suggests that provider characteristics can affect their screening practice. However, no articles about training for depression screening in older adults was encountered.

Depression Screening Training

No recent articles about training primary care practitioners to use depression screening with older adults have been identified. However, a recent article on depression screening training for primary care practitioners who work with adolescents has been found. Fallucco, Seago, Cuffe, Kraemer, and Wysocki (2015) involved 31 practitioners in a training program for a specific depression management system for adolescents; the adolescent patients of those practitioners (n=582 pre-training) were also involved. The results included improved knowledge, confidence and greater odds of diagnosing depression.

The study is relatively small, but it includes a follow-up, which showed continuous improvements. As a result, the study demonstrates that training can indeed affect a practitioner’s ability to diagnose depression. However, it is not considering the practitioners who screen older patients, which is why it is not fully relevant to the project. No other peer-reviewed recent article on the topic or similar topics was found, however, which is why this study is used here.

Screening Tools

With the above-established challenges in healthcare (Espinoza & Unützer, 2015), as well as the widespread nature of depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2017), depression screening among older adults is clearly a significant clinical problem. As a result, it is critical to identify a tool that can be used for such screening. Specifically for geriatric patients, the GDS has been developed, which has been tested with older adults to demonstrate its validity and reliability.

According to a study by Conradsson et al. (2013), its correlation with the Mini-Mental State Examination indicated no significant differences, and the Cronbach’s alpha was ranging between 0.6 and 0.8. As a result, the authors suggested that there was some evidence to the usefulness of the scale, although more research would be required for ensuring that the conclusion was applicable to different groups within the older population.

It is important that the authors used a version of GDS; also, the study only involved 834 participants aged over 85, which may result in limited generalizability. Still, the findings indicate the GDS can be used with older adults, as it was intended to be.

A better-researched scale is the PHQ-9 tool, as pointed out by El-Den, Chen, Gan, Wong, and O’Reilly (2017). The authors conducted an overview of literature between 1995 and 2015, showing that 14 studies over that period had been dedicated to PHQ-9, proving its validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha up to 0.89). In a similar study that focused on a meta-analysis of 40 studies, Mitchell, Yadegarfar, Gill, and Stubbs (2016) demonstrated that PHQ-9 was a workable tool for initial screening with a decent specificity, although its sensitivity was lower than that of a shorter version of the same tool.

Finally, a meta-analysis by Moriarty et al. (2015) demonstrated that PHQ-9 was better-suited for primary care settings due to its high specificity and lower sensitivity. In other words, the use of PHQ is supported by multiple recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which offer a high level of evidence (Polit & Beck, 2017).

To summarize, PHQ-9 is a good tool for initial screening in primary care that is exceptionally well-studied. However, it is not meant specifically for older adults, which, given the importance and challenges of screening for depression in this population (Espinoza & Unützer, 2015; Zaccagnini & White, 2014), may be a problem. On the other hand, GDS is meant specifically for older adults, but it is not as well-studied. Thus, when older adults are considered, both tools might be a good solution, which calls for their use in the present project.

Strengths and Limitations of the Evidence

The presented evidence has some significant strengths and limitations. On the one hand, all the presented literature is peer-reviewed and recent; the oldest source comes from 2014. These features imply that the information is likely to be reliable, high-quality and not outdated yet (Polit & Beck, 2017). Many of the presented studies (five) were literature reviews or meta-analyses, which makes them a source of very high-level evidence.

Furthermore, the rest of the articles were single quantitative studies, which are also relatively high on the evidence pyramid (Polit & Beck, 2017). However, many of the studies, especially the ones that are particularly relevant, cite a lack of evidence on the topic. For example, the systematic review by O’Connor et al. (2016) shows that the number of articles to be reviewed on older adults’ depression screening in primary care is very small. Similarly, no evidence at all can be found about relevant training for providers.

Finally, while most of the quantitative studies had large and even nationally representative samples, there are still limitations to their applicability, predominantly related to different groups within the population studied. Therefore, the presented evidence is strong in that it is produced by high-quality and high-level sources, but it is also very limited. As a result, it is not possible to claim that screening is likely to improve health outcomes in older populations or that screening training has significant effects on depression screening. However, it is clear that the presented tools for depression screening are reliable.

Application to Practice

Based on the presented evidence, it is not reasonable to assume that depression screening will have positive outcomes because the research supporting this idea is not very robust. What does follow from the evidence is that depression screening tends to result in more depression diagnoses. Additionally, it cannot be claimed that the evidence supports depression screening training in practitioners who work with older adults, but it does suggest that depression screening training can have certain effects, including increased depression diagnoses. Finally, the evidence demonstrates that GDS-30 and PHQ-9 are valid and reliable tools.

Therefore, it was possible to carry out a training that would assist practitioners in the use of GDS-30 and PHQ-9 for screening depression with depression diagnoses as the measurable outcome. This way, the significant problem of the lack of screening in primary care, which may be attributable to the lack of training, was addressed through evidence-based and (in the case of GDS) tailored solutions. Their application in the present study could also contribute more data on their usability with older geriatric patients.

Proposed DNP Project Purpose

The presented evidence also provides a ground for the project’s purpose. Specifically, due to the information demonstrating the lack of depression screening in primary care, the issues with ensuring training on depression screening in that setting, and the fact that GDS-30 and PHQ-9 are suitable for screening depression, the purpose of the project was to develop and carry out a training on depression screening in primary settings with a focus on the geriatric population. Guided by the presented evidence, the training was then tested to determine its ability to impact the number of referrals over the course of several weeks.

EBP Action Plan

The goal of this project was to carry out a training for the practitioners of the selected site and determine its effect on the number of patients referred to mental health evaluation based on the results of the application and interpretation of PHQ-9 and GHS. Additionally, the applicability of both tools to geriatric patients was considered an objective.

Population

The project involved training, which is why the main population of interest was primary care providers. The fact that primary care providers require training in the field of depression screening is supported by the importance of this procedure (American Psychiatric Association, 2017).

Additionally, the study involved patients, specifically older adults (65 years or older). The primary justification for that is that depression screening among older adults is more complicated than among younger people (Espinoza & Unützer, 2015). This approach to selecting a population for a training project mirrors the design of other literature (Fallucco et al. 2015). It was planned to involve around 10 practitioners and 15 patients.

Setting

Primary healthcare settings were chosen for the project, with a center that the researcher had access to providing permission to carry out the project. Additionally, the managers of the center were helpful in assisting with the education section of the project. The stakeholders, therefore, included the providers, patients, and managers of the stated center. Given that the tools (PHQ-9 and GDS) are meant for preliminary screening that can identify the need for a referral for a mental health evaluation, the selection of the setting was justified.

Conceptual Framework

Kurt Lewin’s Change Model is very often used in nursing practice, and it has been applied in the described effort (Ellis & Abbott, 2018; Spear, 2016). Specifically, the unfreezing stage included identifying existing practices and providing critical information via the training; the change involved the practitioners applying the tools according to their new knowledge. The refreezing could not be carried out within the limited amount of time that was provided for the project and because of the coronavirus outbreak, but it has been started due to the participants becoming better equipped to handle the tools correctly.

Procedures

After their recruitment, the practitioners who were involved were requested to apply the screening tool PHQ-9 to the recruited patients (65 years or older). Following that, the participants were subjected to training, which included modules on depression, the importance of screening and its application, and the two tools and their appropriate use. After six weeks, the participants were asked to apply the GHS to the same patients. The data were de-identified and transferred to the researcher according to the below-described data collection procedures.

Data Collection

Based on the research question, the dependent variable is the number of patients referred for mental health evaluation as identified with the help of their GDS-30 and PHQ-9 evaluations (see Appendices B and C). The questionnaires were the primary tools of data collection as a result; their validity and reliability are demonstrated by the above-cited literature (Conradsson et al., 2013; El-Den et al., 2017).

Additionally, some demographic information was collected about the practitioners with the help of a short questionnaire, which included questions about their position and experience. The results of the data analysis are presented below.

Data Analysis

All the data were analyzed statistically; descriptive statistics were used to report the key outcomes (Excel was employed for that purpose), and inferential statistics were used to test for correlations between datasets (SPSS was employed for that purpose). Because of the small sample, the study had to use non-parametric tests with the significance level of 0.05 (Hollander, Wolfe, & Chicken, 2013; Polit & Beck, 2017).

It was necessary to employ the sign test for a comparison of the pre- and post-test results in the number of referrals (Hollander et al., 2013). Additionally, correlations were searched for between the results of the two different data collection tools (Polit & Beck, 2017).

Human Subjects Protection

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) was important for the research because of the human subjects involved (Polit & Beck, 2017). It should be pointed out that the risks of participation for participants and patients were minimal; the former only received some additional education, which would not be expected to have negative effects on their careers; the latter were subjected to assessments that would, at most, lead to their referral for reevaluation. As a result, it can be suggested that the risks were almost nonexistent.

Still, all the participants and patients were provided with information about the project, and their informed consent was solicited. Their data were protected through de-identification (the removal of identifying data and its substitution with numbers and roles, for example, Patient 1). Additionally, the hard copies of the information will not be provided to anyone but the provider who handled them. All the data that were sent to the researcher will be kept by a secure, password-locked computer for three years and then destroyed. No hard copies were provided to the researcher.

Organizational Factors

The organizational factors that were involved in the project were facilitators. The permission to carry out the study was obtained, and the participants were enthusiastic about the training opportunity. However, a major issue was the coronavirus pandemic, which hindered the data collection efforts. Some of the participants still managed to provide their information, which proves their enthusiasm and willingness to assist with the project. Overall, no significant organizational barriers were encountered.

Outcome Evaluation

Participant Demographics

The demographics of the participants can be summarized as follows. A total of nine people was involved. The majority of them were nurses (four people; 45%) followed by nurse practitioners (three people; 33%) and nurses (two people; 22%), as can be seen in Figure 2. Moreover, 56% (five people) reported having some experience with both tools; two people had experience with PHQ-9 only, and two (22%) people reported no experience with either of the tools. Thus, the majority of the participants had had some experience in working with the tools prior to participating in the research.

Results

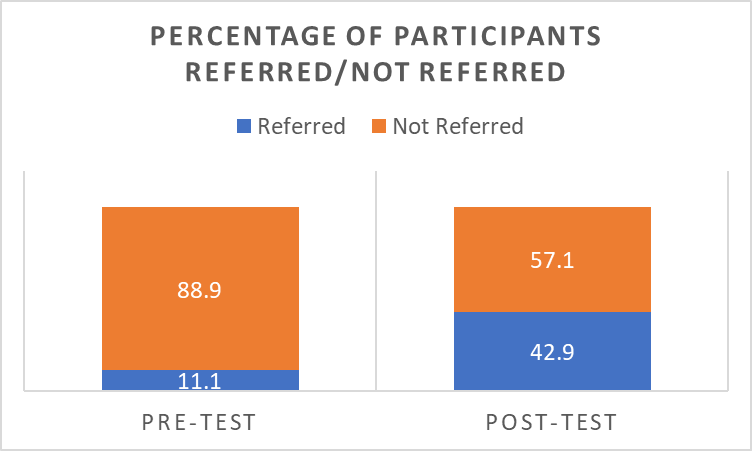

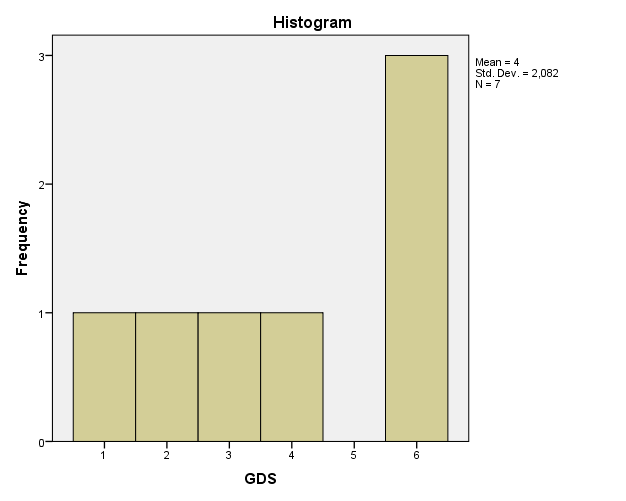

While the total number of patients that were supposed to be recruited amounted to 15, only nine of them submitted PHQ-9, and six weeks later, only seven completed GDS. Before the training, one patient out of nine was referred (11%). After the training, 42.9% of the seven patients were referred (see Figure 3). In other words, the number of the referrals increased dramatically.

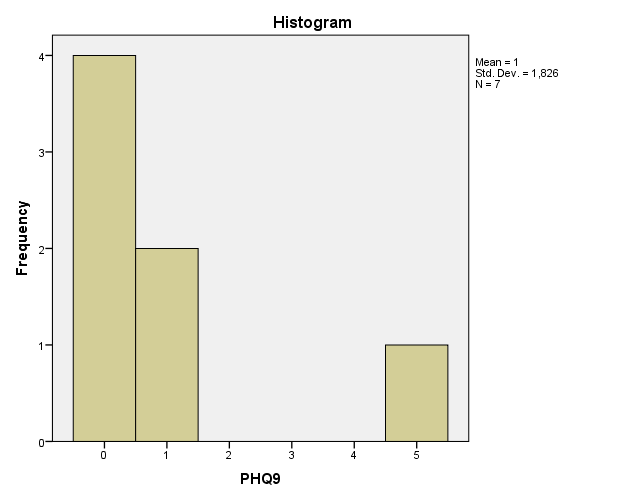

The total scores for PHQ-9 and GHS are presented in Figures 4 and 5. The histograms clearly show that the distribution of the data was abnormal, which prevented the use of parametric tests. As a result, to check for correlations between the data, Kendall’s tau and Spearman’s rho were used (Polit & Beck, 2017). As can be seen from Table 1, no significant correlations between the two datasets were found. Since the results do not correlate very much, the differences in the provided datasets are not unsubstantial.

Table 1. Nonparametric Correlation Test Results.

Additionally, it should be pointed out that due to the incredibly small sample (which was the result of the coronavirus pandemic), parametric tests were not applicable to the collected data (Hollander et al., 2013; Polit & Beck, 2017). Thus, the project used a non-parametric test that could be applied to dependent groups to determine if a statistical difference could be found between the numbers of referrals before and after the training.

The results of the sign test, which is an appropriate nonparametric option for data that do not fit other nonparametric alternatives for pared t-test (Hollander et al., 2013), suggested that no statistically significant difference can be found within the presented data (see Table 2). Indeed, with p greater than 0.05, the results of this study cannot be used to claim that the training has affected the number of referrals in a statistically significant way.

Table 2. Sign Test Results.

Discussion

A summary of the results can be presented as follows. The intended numbers of participants were recruited, but their data were not collected because of the coronavirus. Even with the limited sample, the differences in the percentage of referred patients prior to and after the training has increased, which is in line with the existing research. Indeed, there are studies which suggest that training can increase the number of diagnoses (and, therefore, referrals) (Fallucco et al. 2015), and in general, the use of screening is shown to increase the number of diagnoses in some studies (Randle et al., 2019), even though other studies might contradict this finding (Rhee et al., 2017).

Importantly, the study by Randle et al. (2019) focused not on the statistical significance but the general increase in the percentage of diagnoses. In the current project, the percentage has increased, but no statistical significance in the numbers was found. It should be pointed out that the sample was very small; with such a small sample, it is not reasonable to find the results conclusive (Polit & Beck, 2017).

However, it can be stated that the project failed to find a statistically significant difference in the numbers of referrals after the implementation of a depression screening training for primary care practitioners working with older people. It can also be mentioned that no correlation was found between PHQ-9 and GDS, which is why the project cannot provide conclusions about their ability to confirm each other’s validity. Thus, the findings of the project are defined, in large part, by its limitations.

Limitations

The project was limited by its very small sample, which was further diminished in size by the coronavirus pandemic. Eventually, only seven patients were able to complete GHS. The findings have to be considered from this perspective: they do not imply that the training has had any statistically significant effects, but they also cannot be used to claim the opposite. In the end, more research is required to test the presented training, as well as PHQ-9 and GHS, with a more diverse and larger sample and in other settings (Polit & Beck, 2017), which should help to advance the findings’ generalizability.

Implications for Practice

Based on its data, the study cannot be used to claim that either of the tools is a valid (or more valid) instrument for older adults, and it cannot imply that the presented training has increased the number of referrals in a statistically significant way. Furthermore, the impact of those referrals on patient health and well-being cannot be demonstrated.

However, the study did indicate that some of the providers (22% of the sample) might lack the knowledge about commonly used screening tools and could benefit from related training. With the major limitations that are, among other things, the result of the coronavirus, it may be logical to carry out additional similar studies to further test the presented training and its outcomes.

Implications for Future Research

The present project offers some implications for future research, which are mostly the result of the issues that have been encountered. Thus, because of the small sample, the findings cannot be used to make suggestions about the effectiveness of the training or the validity of the tools. Therefore, future research needs to offer greater samples. Furthermore, in the case of the present project, the coronavirus pandemic became the primary issue that reduced the sample.

Future research can benefit from establishing precautions for various events that can disturb data collection procedures. Naturally, it cannot be claimed that a global pandemic could have been predicted, but it is noteworthy that with the modern technology, online data collection is a possibility. For the present study, no online option was initially planned, and no permission (including IRB permission) for it was attained. As a result, it was not possible to use it, but a future study might propose an additional data collection option at the stage of planning for the project.

A future study may offer a project that is dedicated to training; it could consider more outcomes, the suggestions for which can be found in the reviewed literature. For instance, practitioner knowledge and confidence can be important (Fallucco et al., 2015). The fact that the participant knowledge of the tools was found to be lacking in 22% also suggests a need for studies which would consider the level of education and training that practitioners currently exhibit in primary care settings.

Furthermore, a future study could focus on checking the validity of the two tools by applying them to the same rather large population (Polit & Beck, 2017). In the present study, the correlations were not very useful because they were applied at different times (before and after training). A future study can commit to determining the validity of both tools and focus on it instead of training.

Finally, the literature review clearly demonstrates that the topic, which was chosen for this study, is not very well-researched. More studies are required on depression screening in older adults, which is especially true because of the vulnerability of the population and the difficulties in diagnosing them (O’Connor et al., 2016). The present study offered a small contribution to this topic, including the observation that the training of practitioners might indeed be necessary, but since its findings are not conclusive, more investigation is required.

Conclusions

This report details the results of a study dedicated to training practitioners to use PHQ-9 and GDS with older adults in primary care settings. The justification of the project is that the condition is very widely spread but remains underdiagnosed and that in older people, diagnosing depression is difficult. Additionally, there is little research on depression screening training, and no such research on primary care practitioners who work with older adults was found. Therefore, the project covered a research gap and focused on a significant issue.

The project involved nine practitioners in a series of training sessions aimed to improve their ability to use PHQ-9 and GDS; 22% of the sample did not know enough about the two tools to apply them. Before the training, the participants referred only one patient, and after the training, three patients were referred.

However, the small sample meant that the data could not demonstrate a statistically significant difference. Additionally, no correlation between the scores of the two tools was found, which is why no evidence of the two tools’ validity was supplied by the project. Still, the research shows that the lack of training may indeed affect primary care professionals, which calls for a more extensive project with a larger sample when the coronavirus restrictions are lifted.

References

Akincigil, A., & Matthews, E. (2017). National Rates and patterns of depression screening in primary care: Results from 2012 and 2013. Psychiatric Services, 68(7), 660-666. Web.

Al-Qadhi, W., Rahman, S., Ferwana, M.S., &Abdulmajeed, I. A. (2014). Adult depression screening in Saudi primary care: Prevalence, instrument and cost. BMC Psychiatry,14(1), 1-9. Web.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder (5th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (2017). Depression screening rates in primary care remain low. Web.

Cohen, B. E., & Edmondson, D., I. M. (2015). State of the art review: Depression, stress, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Hypertension,28(11), 1295-1302. Web.

Conradsson, M., Rosendahl, E., Littbrand, H., Gustafson, Y., Olofsson, B., & Lövheim, H. (2013). Usefulness of the geriatric depression scale 15-item version among very old people with and without cognitive impairment. Aging & Mental Health, 17(5), 638-645. Web.

El-Den, S., Chen, T. F, Gan, Y. L., Wong, E., & O’Reilly, C. L. (2018). The psychometric properties of depression screening tools in primary healthcare settings: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 503-522. Web.

Ellis, P., & Abbott, J. (2018). Applying Lewin’s change model in the kidney care unit: Movement. Journal of Kidney Care, 3(5), 331-333.

Espinoza, R. T., & Unützer, J. (2015). Diagnosis and management of late-life unipolar depression. Web.

Fallucco, E., Seago, R., Cuffe, S., Kraemer, D., & Wysocki, T. (2015). Primary care provider training in screening, assessment, and treatment of adolescent depression. Academic Pediatrics, 15(3), 326-332. Web.

Farrer, L. M., Gulliver, A. G., Bennett, K., Fassnacht, D. B., & Griffiths, K. M. (2016). Demographic and psychosocial predictors of major depression and generalised anxiety disorder in Australian university students. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 241. Web.

Fekadu, N., Shibeshi, W., &Engindawork, E. (2017). Major depressive disorder: Pathophysiology and clinical management. Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 6(1), 255-261. Web.

Ferenchick, E. K. (2019). Depression in primary care: Part 1—screening and diagnosis. BMJ, 365, 1-10. Web.

Hollander, M., Wolfe, D. A., & Chicken, E. (2013). Nonparametric statistical methods. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Kok, R., & Reynolds, C. (2017). Management of depression in older adults. JAMA, 317(20), 2114-2122. Web.

Mitchell, A. J., Yadegarfar, M., Gill, J., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Case finding and screening clinical utility of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2) for depression in primary care: A diagnostic meta-analysis of 40 studies. BJPsychOpen, 2(2), 127-138. Web.

Moriarty, A., Gilbody, S., McMillan, D., & Manea, L. (2015). Screening and case finding for major depressive disorder using the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 37(6). 567-576. Web.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2019). Major depression. Web.

O’Connor, E., Rossom, R. C., Henninger, M., Groom, H. C., Burda, B. U., Henderson, J. T.,… Whitlock, E. P. (2016). Screening for depression in adults. Web.

Park, M., &Unützer, J. (2011). Geriatric depression in primary care. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 34(2), 469-487. Web.

Pfizer Inc. (1999). Patient Health Questionnaire. Web.

Pfoh, E., Janmey, I., Anand, A., Martinez, K., Katzan, I., & Rothberg, M. (2020). The impact of systematic depression screening in primary care on depression identification and treatment in a large health care system: A cohort study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2020. Web.

Polit, D.F., & Beck, C.T. (2017). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (10th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Randle, A., Spurlock, A., & Kelley, S. (2019). Depression screening among African American Adults in the primary care setting. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing And Mental Health Services, 57(10), 18-23. Web.

Rhee, T., Capistrant, B., Schommer, J., Hadsall, R., & Uden, D. (2017). Effects of depression screening on diagnosing and treating mood disorders among older adults in office-based primary care outpatient settings: An instrumental variable analysis. Preventive Medicine, 100, 101-111. Web.

Spear, M. (2016). How to facilitate change. Plastic Surgical Nursing, 36(2), 58-61.

Thabet, J. B., Turki, M., Mezghanni, M., Bouali, M. M., Charfi, N., Omri, S.,… Maalej, M. (2017). Depression screening in primary care patients. European Psychiatry, 41(S1), S543-S544. Web.

Yesavage, J., Brink, T., Rose, T., Lum, O., Huang, V., Adey, M., & Leirer, V. (1982). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17(1), 37-49. Web.

Zaccagnini, M. E., & White, K. W. (2014). The doctor of nursing practice essentials: A new model for advanced nursing practice. New York, NY: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Appendix A

Evidence Table.

Appendix B

PHQ-9 Scale.

Appendix C

GDS-30 Scale.