Introduction

Dementia is a significant health concern, both worldwide and within the United Kingdom. According to Dementia hotspot maps (2018), it affects 850,000 people in the nation, distributed unevenly across territories and age ranges. The condition is typically associated with seniors, and the number of people with it will likely increase as the average life expectancy of people in the UK grows.

Moreover, people affected by it are prone to having cognitive difficulties that can make them incapable of safe independent functioning. The affected people may struggle with remembering facts, organising themselves, or handling complicated tasks and become confused in general. In the case of Parkinson’s disease, a subtype of dementia of particular interest to the researcher, their movement is also impaired in various ways. As such, they require attention from either family members or dedicated caretakers, which incurs substantial expenditures of time, money, and effort. As such, dementia is problematic both due to its effects on the people affected and the overall economic impact it has on society.

However, the condition is still not well-understood in terms of either prevention or treatment, and many of its results do not currently appear to be reversible. Research is ongoing, but it has not generated many noteworthy results that have been integrated into treatments. Hodges and Piguet (2018) assert that, while the understanding of dementia and the ability to predict its emergence have advanced dramatically in the last two decades, this growth has not been reflected in drug development. Medications for dementia prevention and management are still lacking, and the condition emerges regardless of the efforts made to stop it. This fact raises the question of the topics currently being explored and the progress that has been made in them. To that end, this paper aims to evaluate the current literature and answer the following questions:

- What are the common causes of dementia?

- What themes does basic and clinical research into dementia and Parkinson’s disease follow?

- What potential pharmacological treatments can be used for dementia, and how advanced is the research into them?

Methods

Ethical Approval Statement

The research method selected for the study only works with literature that is available publicly or through databases that the researcher can access. Hence, there are no ethical concerns regarding participants, such as informed consent or privacy. To avoid the ethical concerns surrounding the review, this paper presents the information gathering process clearly so that it can be reproduced and assessed by a reader.

Research Design

This project aims to explore the current state of research in the field of dementia, determining the areas where the most progress has been made and focusing on several specific concepts. To that end, a qualitative approach appears to be better suited to the purposes of the study than a quantitative method. Instead of a series of well-defined hypotheses, the study begins with several broad questions and explores details as it progresses. As such, a quantitative research design appears to be inappropriate, while the qualitative approach is specifically intended for the study’s purposes. A mixed design is unnecessary, as well, as this study aims to provide a general overview from which more specific inquiries can be derived later on. Overall, a qualitative design appears to be optimal, given the purposes of the research and the results that it seeks to achieve.

Research Methodology

As the purpose of the study is to analyse the current state of research surrounding dementia and its potential treatments, a literature review approach appears to be most well-suited for the situation. It enables the researcher to collect information efficiently by consulting scientific databases and selecting research that has been peer-reviewed and processed into easily understood data. Moreover, through literature analysis, they can collect a plurality of viewpoints and identify the consensus in the field as well as any debates that may be taking place. A systematic literature review is the specific methodological approach chosen for the study because of the structure of the research. The analysis stems from several specific questions and is centred on them, aiming to create a framework that encompasses the current body of research. As such, compared to narrative or integrative literature reviews, the systematic method appears to satisfy the study’s requirements better.

Research Method

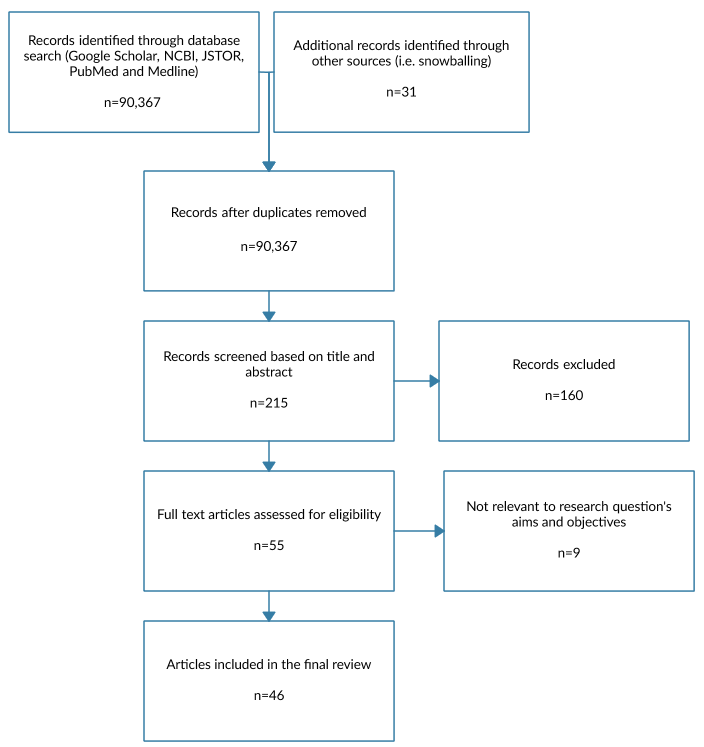

As the research methodology for this study is a literature review, it has worked exclusively with secondary data sources. They were collected via several databases that categorise scientific articles on medical topics, such as Google Scholar, NCBI, JSTOR, PubMed and Medline. The primary keywords used for the search were “dementia”, “Parkinson’s disease”, “causes”, and “treatment”. A variety of secondary keywords was also used, including “pharmacological”, “research”, “clinical trial”, and others. Boolean operators were also used where necessary to isolate more specific topics or improve the range of the search. A relevancy requirement was imposed, as well, with the articles required to be five years old or less. The researcher then reviewed a portion of the articles discovered through these searches, as they did not have the time to analyse all of the results. The results of the data collection process are presented in the PRISMA diagram shown in Fig. 1.

Data Analysis

As the study is qualitative in nature and constitutes a meta-synthesis of contemporary studies, framework analysis is the most appropriate to its purposes. It enables them to process a diverse selection of literature and derive specific themes from it. These themes can then be used to categorise the data and find answers to each of the questions asked in the study. To find them, the researcher first familiarised themselves with the contents of each of the articles and identified a basic set of themes. They then employed coding to highlight more specific data and similarities between different studies. Based on the results, they separated the articles into different sections that pertained to different aspects of the research questions. Based on the information contained within those articles, they were able to interpret the information and obtain a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Results

Research Themes

Current research into dementia is advancing on several different fronts, aiming to improve the understanding of the condition and explore potential options for managing and treating it. Pickett et al. (2017) posit five goals for future studies: dementia prevention, maximising benefits to people living with dementia, improving their quality of life, improving the competencies of the dementia workforce and optimising the quality and inclusivity of available health services. In acknowledgement of the condition’s currently incurable nature, the goal of treating it fully has not been included, a pattern that repeats throughout the research.

Instead of seeking to eliminate dementia in patients who currently have it, researchers aim to prevent it and minimise the issues that it causes in the lives of those affected. With that said, research is ongoing into an improved understanding of the condition, which may eventually lead to the development of comprehensive treatments.

The research into the causes of dementia is still ongoing, and it appears to mostly focus on the genetic aspect of the condition. Per Goldman and Van Deerlin (2018), new sequencing technologies have enabled physicians to test for multiple overlapping conditions concurrently, though they still have numerous limitations that have to be considered in practical use. However, genetics do not necessarily account for all dementia cases, particularly with regard to Alzheimer’s disease. dos Santos et al. (2017) notes that an overwhelming majority of its occurrences is sporadic and presents several competing hypotheses for the onset of the condition, which discuss different processes that may be responsible for the formation of markers.

Alber et al. (2019) discuss white matter hyperintensities, which contribute to the emergence of dementia but can also be controlled to some extent, both pharmacologically and otherwise. Overall, rapid progress is taking place, but the mechanisms behind dementia are still not well-understood in the holistic sense, with many disparate phenomena with unclear connections taking place.

In the absence of ways to overcome the effects of dementia entirely, a substantial body of research has focused on improving the quality of life of the people affected by it. Kolanowski et al. (2018) provide a list of recommendations that are separated into four categories: better understanding the symptoms and meaningful interventions, improving ways for people to live with dementia, advancing dementia care and integrating technology in every aspect of support.

Due to the rapid and continuous evolution of knowledge and technology, this field is constantly evolving as new ways to address needs efficiently are discovered. Moreover, Martyr et al. (2018) conduct a review of quality-of-life factor studies that involve dementia patients and find considerable heterogeneity in the findings as well as a lack of longitudinal predictor evidence. As such, data about maintaining or improving it is lacking, and more research into that aspect of care is required.

In terms of pharmacological treatments, there is a considerable diversity of options due to the substantial variation between different dementia types. Per Arvanitakis, Shah and Bennett (2019), FDA-approved drugs for Alzheimer’s disease are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (namely, donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine), NMDA receptor antagonists such as memantine, or donepezil and memantine used together.

These treatments are able to slow the patient’s decline somewhat, but they are also associated with adverse side effects. Chu et al. (2018) consider the use of statins to reduce dementia risk and find that they reduce the probability of all-type dementia and Alzheimer’s disease but do not affect vascular dementia. With that said, the topic of their usage remains controversial, with studies available that both support the finding and fail to find any association.

Research is also ongoing into potential treatments that have not yet been put into widespread practice. Tewari et al. (2018) consider the usage of medicinal plants and drugs based on them to combat dementia, highlighting their potential ability to circumvent the adverse effects synthetic medications have. However, research into them is still lacking, and additional studies are required before the determination of the viability of plant-based compounds for dementia treatment. Chen et al. (2019) instead consider the usage of tamoxifen to restore white matter and cognitive functions, though the trial is still operating on mice. If the drug is found to achieve its purpose, it can significantly advance current knowledge regarding the treatment of dementia. However, it is still considerably far from practical adoption, and the proposition is mostly theoretical.

With regard to Parkinson’s disease, research is ongoing into early detection and prevention of the condition. Aarsland et al. (2017) claim that the early stages of the condition, characterised by mild cognitive decline, can be used as an early indicator in combination with several biomarkers. At these stages, it is possible for the patient to return to normal cognition, potentially preventing the continued decline that eventually ends in dementia.

With that said, the treatment of Parkinson’s disease is still complicated, even in these early stages, as the methods used are often unable to slow down the progress of the condition. Stoker, Torsney and Barker (2018) highlight potential future methods of addressing this problem through measures such as restoring the patients’ dopaminergic deficits and reducing the levels of pathological α-synuclein. While the former will have to be accomplished via novel cell- and virus-based therapies, the latter could be achieved with medications such as rapamycin, trehalose, exenatide and nilotinib.

Causes of Dementia

First and foremost, it should be noted that dementia is not a singular condition but rather a set of symptoms that tend to manifest simultaneously and lead to similar outcomes regardless of the root cause. Still, differences tend to manifest based on the underlying condition, and, as such, dementia is typically divided into a number of types. With that said, per James and Bennett (2019), these categorisations may not necessarily be meaningful, as in the case of Alzheimer’s disease, which is generally considered the most prevalent cause of dementia, patients are typically found to have evidence of other related conditions, as well. One of the prominent reasons why dementia is typically associated with seniors is that brain pathologies tend to accumulate over time, and occasionally, they develop enough to impair the person’s functioning.

While this gradual increase in the number of different sources of brain damage is generally considered the primary cause of dementia in most cases, other causes for specific dementia types have also been discovered. Hodges and Piguet (2018) consider frontotemporal dementia and find that most of its familial cases are predetermined genetically, with research into the C9orf72 gene taking place rapidly as it has been found to be a significant predictor. Similar findings have been made for Alzheimer’s disease, as well, with the APOE gene as well as 23 other genetic variants associated with it (van der Lee et al., 2018). With that said, research is still ongoing, and, as Orme, Guerreiro and Bras (2018) state, some types of dementia, notably the Lewy bodies variant, have not been studied adequately from the genetic perspective. However, research is actively ongoing, as the importance of the factor has been recognised in the field.

The genetic nature of dementia is problematic because it means that the condition is highly challenging to prevent or treat. However, research has also focused on lifestyle as a potential cause of brain damage that accumulates over the years to manifest late in one’s life. Lourida et al. (2019) find in a retrospective cohort study of nearly 200,000 people that a healthy lifestyle could reduce one’s dementia risk relative to the rest of their genetic risk group.

The specific lifestyle aspects that can affect the incidence of dementia are not yet fully known, however. Tariq and Barber (2018) list “mid-life hypertension, mid-life obesity, diabetes, physical inactivity, smoking and depression” as the modifiable biological factors that can increase the likelihood of one developing the condition later on (p. 568). At the same time, dos Santos Matioli et al. (2017) conduct an isolated study of diabetes and find that it has little to no effect on the onset of dementia. As such, research is still ongoing, and the understanding of the relationship between lifestyle and dementia has not been explored in sufficient detail.

Psychosocial factors are also involved in the development of dementia, as some of them can contribute to nervous system damage. Terracciano et al. (2017) find that, measured using the Big Five personality trait framework, low agreeableness and conscientiousness, as well as high neuroticism, contribute to the likelihood of one eventually manifesting the symptoms, regardless of age, race, gender, ethnicity, or education.

One’s character can influence the likelihood of them developing dementia both through lifestyle habits typically associated with it and other, possibly more direct pathways. Additionally, Fratiglioni, Marseglia and Dekhtyar (2020) find that a number of factors not necessarily within one’s control, such as higher socioeconomic status, longer time spent in education, lower work stress, high occupational complexity and engagement in various mental and social activities all reduce the probability of dementia. The presumed cause is that regular exercise of one’s mental faculties without overexerting them helps prevent brain matter decline.

Parkinson’s disease warrants a separate mention due to the study’s focus on it as well as the situation surrounding the condition. Bhat et al. (2018) state that it is severely understudied, with 80% of cases currently not attributable to any particular cause, while the remaining 20% are believed to be genetic in nature. The current assumption is that it is mostly caused by genetic predisposition combined with specific life experiences, but the specifics are unclear. From the genetic standpoint, most Parkinson’s disease cases associated with this cause are hereditary, with monogenetic cases possible but considered rare (Tysnes and Storstein, 2017). With that said, research into other factors is ongoing, with Chen, Turnbull and Reeve (2019) highlighting mitochondrial dysfunction as a potential cause. It is associated with the condition and contributes to the decline that results from Parkinson’s disease, but which of the two leads to the other is currently not clear.

In the case of Parkinson’s disease, dementia is typically a sign of the condition entering a late stage. As stated above, in many cases, the decline will happen over time as the condition’s severity increases. However, Sheu et al. (2019) find that patients taking anticholinergic medications, which are often prescribed for treating the motor symptoms of the condition, manifest significantly higher chances of developing dementia than their counterparts without such treatments.

This problem is one of the many downsides current treatment methods have, which are beginning to be discovered as research advances. Among the more recent developments in the field is the study of the pathology of Parkinson’s disease dementia and its comparison with that of Lewy body dementia, which are often considered extremely similar but have recently been found to differ somewhat, leading to controversy (Jellinger, 2018). This development demonstrates that Parkinson’s disease dementia is not yet fully understood, and further research is required.

Overall, it can be seen that the specific causes of dementia are challenging to track because of its nature. It may be possible to determine whether one is predisposed to it genetically, though research in that field is still rapidly developing, with many fields unexplored and questions unanswered. The other part is the accumulation of brain damage over time, which can be challenging to address, especially since it presents no symptoms for most of the person’s life.

This damage is also mostly irreversible (Arvanitakis, Shah and Bennett, 2019), which means that much of dementia treatment research focuses on early prevention. With that said, Zucchella et al. (2018) highlight a number of non-pharmacological treatments that can help enhance the function, independence and quality of life of patients with dementia. While overcoming the condition entirely through such measures is not feasible, the effects may be mitigated to some extent.

Pharmacological Treatments

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) are a type of cholinesterase inhibitors that are often used for the treatment of most dementia variants. Per Knight et al. (2018), their usage is associated with moderate improvements in patients’ Mini-Mental State Examination results, though the result is moderated by the dementia type. This overall effectiveness has made them a highly popular choice that has secured FDA approval, as highlighted above. With that said, this drug category is also associated with some issues and has been undergoing a re-evaluation recently. Parsons et al. (2021) test the effects of AChEIs’ withdrawal and find that they are not necessarily clear, especially in the medium and long term. Niznik et al. (2020) find that, in cases of severe dementia, deprescribing them reduces the risk of the patient being involved in negative events from any cause. For these patients, any worsening of the symptoms is unlikely to be significant, but the drugs increase the risk of falls and fractures.

Among AChEIs, rivastigmine is of particular interest because it differs from the rest significantly. Kandiah et al. (2017) claim that it is unique in its suppression of both acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase, which may lead to improvements in the recipient’s cognition and behavioural symptoms. With that said, rivastigmine is also associated with significant problems that are beginning to surface with its increased adoption.

Kazmierski et al. (2018) find that it is associated with an increased risk of death in long-term use when compared to donepezil, another drug in the same category. Li et al. (2019) recommend using galantamine as the primary treatment drug, though they note that the data in this regard is still limited. Overall, the recent discovery of the significant adverse effects of rivastigmine has spurred investigations into the safety and efficacy of the overall category.

Memantine is another option that has been discussed extensively in recent literature, as it can be used alongside AChEIs. Instead, it suppresses N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptors, the excessive activity of which is associated with neuron loss (Folch et al., 2018). However, as Folch et al. (2018) note, despite the drug showing highly promising results in preclinical stages, its positive effects in clinical applications appear to be limited. While this result is underwhelming, memantine’s ability to be taken as part of a multi-drug treatment course still makes it a valuable option. Furthermore, McShane et al. (2019) confirm that, while memantine does not necessarily produce powerful effects, it also appears to avoid the adverse implications of many of its counterparts. As such, its continued usage may be advisable for the effective treatment of dementia symptoms.

Lewy body dementia is generally treated the same way as other variants, including the pharmacological component. Stinton et al. (2015) find that the majority of treatment studies for the condition use donepezil and rivastigmine (which once against demonstrates elevated adverse effect risks) with limited evidence for a variety of other drugs. Hershey and Coleman-Jackson (2019) also suggest a variety of other drugs, such as levodopa, zonisamide, valproic acid and pimavanserin, though many of these alternatives are also associated with risks. With that said, research into the pharmacological treatment of Lewy body dementia may show significant gaps. Taylor et al. (2020) assert that the symptoms unique to patients with this type of condition have not been researched and addressed adequately. Instead, treatments are restricted to those already known through the treatment of other dementia types.

Parkinson’s disease dementia demonstrates many of the same aspects as its Lewy body counterpart in terms of treatment. The same drugs are generally used for it as for other types of dementia. As Meng et al. (2018) find, similar conclusions can also be reached, as well, with AChEIs achieving reductions in symptoms at the cost of increased risk, particularly for rivastigmine. Regardless, the drug has been approved for usage with patients demonstrating dementia. With that said, as Hanagasi, Tufekcioglu and Emre (2017) note, memantine has not received approval despite also demonstrating positive effects. The most likely reason is that not enough studies have been conducted demonstrating its efficacy and lack of adverse effects. In the future, this situation is likely to change, leading to increased adoption of the drug.

One problem specific to Parkinson’s disease is the usage of other medication that may increase the probability of patients developing dementia. Hong et al. (2019) and Manza et al. (2017) support the earlier finding that anticholinergics significantly increase the danger of the condition’s onset. With that said, the drug category continues to be broadly applied to treat the motor symptoms of the condition. With that said, the risk of dementia has been recognised, and Zeuner et al. (2018) recommend that the drug category only be used at the early stages of the condition. With that said, there are other Parkinson’s disease-related problematic drug interactions, as well. Notably, atypical antipsychotics, which are often used to manage Parkinson’s disease psychosis, have been found to increase mortality in patients with dementia (Fredericks et al., 2017). At the same time, psychosis presents substantial danger if left untreated, generating a dilemma.

This problem may be addressed through research, particularly since some drugs used to treat dementia appear to have positive Parkinson’s disease-related effects, as well. Seppi et al. (2019) find that rivastigmine’s ability to reduce hallucinations may make it useful in addressing the likelihood of psychosis in patients. Safarpour and Willis (2016) also find a potential for axial motor ability and dyskinesia improvement in Parkinson’s disease patients associated with the use of memantine, but the evidence for these interactions is limited. These traits are insufficient for supporting an overall application of the medications for patients with Parkinson’s disease and without dementia. However, they may be of interest for the treatment of patients demonstrating a multitude of symptoms simultaneously as a result of an advanced-stage condition.

Finally, a discussion of medications that are currently being developed is warranted. Silveira et al. (2019) propose a trial for ambroxol, which, if successful, may be the first disease-modifying treatment for Parkinson’s disease dementia. The drug is well-established, though it is currently used for other purposes. However, its ability to affect β-Glucocerebrosidase may help diminish one of the most significant genetic predictors of Parkinson’s disease dementia, mutations in that gene (Silveira et al., 2019). Ceftriaxone is another promising option, having successfully reversed behaviour and neurogenesis deficits in a rat model of the condition (Hsieh et al., 2017). The drug affects glutamatergic system hyperactivity, which is one of the reasons for neurodegeneration during Parkinson’s disease. These drugs and others that are being developed may change the treatment of the condition as a whole and its dementia component significantly if they are ultimately approved for use on people.

Discussion

Overall, research into dementia appears to still be in an early stage, with many aspects of it still not understood entirely. Some types of it, such as Alzheimer’s disease, have been studied extensively, while others, like Lewy body dementia, are underresearched heavily and not well-understood (Orme, Guerreiro and Bras, 2018). With that said, the situation appears to be changing, as technological and scientific advances have enabled researchers to better understand the genetic component of dementia and use it to predict the risk of one developing the condition. While scientists are also aware of other causes for dementia, namely lifestyle and psychosocial factors, they are unable to isolate any specific aspects that are particularly influential, as the research of dos Santos Matioli et al. (2017) exemplifies. With this lack of knowledge about specific causes, it is also challenging to design personalised interventions beyond living an overall healthy lifestyle.

While there are issues in the understanding of dementia, the situation surrounding Parkinson’s disease is even more problematic. While hypotheses such as that of Chen, Turnbull and Reeve (2019) are being put forward, the condition is still overwhelmingly not understood (Bhat et al., 2018). As a result, its prevention is also highly challenging since it is difficult to determine whether one belongs to a risk group unless they are genetically predisposed to the condition.

Furthermore, current research into Parkinson’s disease focuses strongly on the motor symptoms and the potential for the development of psychosis instead of dementia. As a result, some medications taken for Parkinson’s disease have the potential to promote the development of dementia in addition to their intended effects (Sheu et al., 2019). The recognition of this tendency has led to the proposal of changes to the treatment of patients with the condition, but there are still no dedicated treatments for the purpose.

With both of these conditions not well-understood, research into their treatment has also stagnated to a large degree. The white tissue damage that is associated with dementia is generally considered irreversible, and no known methods exist for stopping or reversing the progression of Parkinson’s disease, either. As a result, medical research focuses on the prevention of dementia throughout one’s life and the improvement of the quality of life of those affected (Pickett et al., 2017). Similar considerations apply to Parkinson’s disease dementia, as medical services are generally unable to affect the chance of the patient progressing to that stage of the condition (Aarsland et al., 2017). With that said, many people with the illness also remain at a mild cognitive decline level or return to normal functioning. With this aspect considered, the relative lack of research on Parkinson’s disease dementia is easier to understand.

The lack of advancement in the understanding of dementia is also reflected in the medications that are currently being used. There is a marked lack of innovation in the treatment of the condition, with the most commonly employed drugs aiming to reduce the patients’ symptoms. Moreover, their usage is still not well-understood, with researchers such as Parsons et al. (2021) and Niznik et al. (2020) questioning the validity of their usage. While some agents, such as rivastigmine and memantine, have been introduced relatively recently, the former is associated with increased risk of adverse effects and death (Kazmierski et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019), while the latter has limited benefits for the patient (Folch et al., 2018). Regardless, these drugs continue to be used due to a lack of alternatives, even if their specific applications have been modified.

The situation surrounding the treatment of Parkinson’s disease dementia is more problematic due to some preconceptions in approaches to it. As Jellinger (2018) states, for a considerable time, it was believed that Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia were essentially the same, but recently, some differences were discovered. As a result, many of the same medications were used, and specialised drugs have not been developed yet. Rivastigmine is frequently used for Parkinson’s disease dementia, while memantine has not been approved despite demonstrating promising results (Hanagasi, Tufekcioglu and Emre, 2017). Still, rivastigmine and memantine show some potential to address the issues of Parkinson’s disease in addition to alleviating the symptoms (Safarpour and Willis, 2016). As such, the other concerns associated with these drugs notwithstanding, they may be applicable in the absence of new options.

While both the understanding of dementia and the development of treatments for it are inadequate at the moment, there are opportunities for the situation to change in the future. Research such as that of Chen et al. (2019) may help restore patients’ white matter, directly reversing the damage that causes dementia. Meanwhile, scholars such as Chen, Turnbull and Reeve (2019) are investigating the mechanisms that cause Parkinson’s disease and influence its progress, with innovative drugs also being proposed. If research continues at this pace, a breakthrough may happen in the foreseeable future that revolutionises the treatment of the conditions. Considering the potential impact of both dementia and Parkinson’s disease in terms of the numbers of people they affect and the costs of treatment, there is a substantial incentive for studies to continue.

Conclusion

Recently, research into dementia of all types has been progressing rapidly, assisted by advances in the understanding of genetics and the improved available technology. However, there are still large gaps in the research body, and many types of dementia, as well as Parkinson’s disease, are still not adequately understood. Moreover, the factors that contribute to the development of the condition are both irreversible and challenging to prevent, as they accumulate over one’s lifetime. As a result, the medications currently used only manage symptoms at a moderate level at the expense of increasing risks to the patients. No promising new medications currently appear to be close to practical adoption, though there are some noteworthy options in the early trial stages. Ultimately, substantially more research is needed before significant advances can be made in the treatment of the condition.

Reference List

Aarsland, D. et al. (2017) ‘Cognitive decline in Parkinson disease’, Nature Reviews Neurology, 13(4), pp. 217-231.

Alber, J. et al. (2019) ‘White matter hyperintensities in vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID): knowledge gaps and opportunities’, Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 5(1), pp. 107-117.

Arvanitakis, Z., Shah, R.C. and Bennett, D.A. (2019) ‘Diagnosis and management of dementia’, JAMA, 322(16), pp. 1589-1599.

Bhat, S. et al. (2018) ‘Parkinson’s disease: cause factors, measurable indicators, and early diagnosis’, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 102, pp. 234-241.

Chen, C., Turnbull, D.M. and Reeve, A.K. (2019) ‘Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease—cause or consequence?’, Biology, 8(2). Web.

Chen, Y. et al. (2019) ‘Tamoxifen promotes white matter recovery and cognitive functions in male mice after chronic hypoperfusion’, Neurochemistry International, 131. Web.

Chu, C.S. et al. (2018) ‘Use of statins and the risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Scientific Reports, 8(1), pp. 1-12.

Dementia hotspot maps (2018). Web.

dos Santos Matioli, M.N.P. et al. (2017) ‘Association between diabetes and causes of dementia’, Dementia & Neuropsychologia, 11(4), pp. 406-412.

dos Santos, P. et al. (2017) ‘Alzheimer’s disease: a review from the pathophysiology to diagnosis, new perspectives for pharmacological treatment’, Current Medicinal Chemistry, 25(26), pp.3141-3159.

Dyer, S.M. et al. (2018) ‘An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia’, International Psychogeriatrics, 30(3), pp. 295-309.

Folch, J. et al. (2018) ‘Memantine for the treatment of dementia: a review on its current and future applications’, Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 62(3), pp. 1223-1240.

Fratiglioni, L., Marseglia, A. and Dekhtyar, S. (2020) ‘Ageing without dementia: can stimulating psychosocial and lifestyle experiences make a difference?’, The Lancet Neurology, 19(6), pp. 533-543.

Fredericks, D., Norton, J.C., Atchison, C., Schoenhaus, R. and Pill, M.W. (2017) ‘Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a perspective on the challenges, treatments, and economic burden’, The American Journal of Managed Care, 23(5 Suppl), pp. S83-S92.

Goldman, J.S. and Van Deerlin, V.M. (2018) ‘Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia: the current state of genetics and genetic testing since the advent of next-generation sequencing’, Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy, 22(5), pp. 505-513.

Gomperts, S. N. (2016) ‘Lewy body dementias: dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson disease dementia’, Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology, 22(2 Dementia), pp. 435-463.

Hanagasi, H.A., Tufekcioglu, Z. and Emre, M. (2017) ‘Dementia in Parkinson’s disease’, Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 374, pp. 26-31.

Hershey, L.A. and Coleman-Jackson, R. (2019) ‘Pharmacological management of dementia with Lewy bodies’, Drugs & Aging, 36(4), pp. 309-319.

Hodges, J. R. and Piguet, O. (2018) ‘Progress and challenges in frontotemporal dementia research: a 20-year review’, Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 62(3), pp. 1467-1480.

Hong, C.T. et al. (2019) ‘Antiparkinsonism anticholinergics increase dementia risk in patients with Parkinson’s disease’, Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 65, pp. 224-229.

Hsieh, M.H. et al. (2017) ‘Ceftriaxone reverses deficits of behavior and neurogenesis in an MPTP-induced rat model of Parkinson’s disease dementia’, Brain Research Bulletin, 132, pp. 129-138.

James, B.D. and Bennett, D.A. (2019) ‘Causes and patterns of dementia: an update in the era of redefining Alzheimer’s disease’, Annual Review of Public Health, 40, pp. 65-84.

Jellinger, K.A. (2018) ‘Dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease-dementia: current concepts and controversies’, Journal of Neural Transmission, 125(4), pp. 615-650.

Kandiah, N. et al. (2017) ‘Rivastigmine: the advantages of dual inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase and its role in subcortical vascular dementia and Parkinson’s disease dementia’, Clinical Interventions in Aging, 12, pp. 697-707.

Kazmierski, J. et al. (2018) ‘The impact of a long-term rivastigmine and donepezil treatment on all-cause mortality in patients with Alzheimer’s disease’, American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 33(6), pp. 385-393.

Knight, R. et al. (2018) ‘A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in treating the cognitive symptoms of dementia’, Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 45(3-4), pp. 131-151.

Kolanowski, A. et al. (2018) ‘Advancing research on care needs and supportive approaches for persons with dementia: recommendations and rationale’, Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(12), pp. 1047-1053.

Li, D. D. et al. (2019) ‘Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials on the efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease’, Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13. Web.

Lourida, I. et al. (2019) ‘Association of lifestyle and genetic risk with incidence of dementia’, JAMA, 322(5), pp. 430-437.

Manza, P. et al. (2017) ‘Response inhibition in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of dopaminergic medication and disease duration effects’, npj Parkinson’s Disease, 3(1). Web.

Martyr, A. et al. (2018) ‘Living well with dementia: a systematic review and correlational meta-analysis of factors associated with quality of life, well-being and life satisfaction in people with dementia’, Psychological Medicine, 48(13), pp. 2130-2139.

McShane, R. et al. (2019) ‘Memantine for dementia’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2019(3). Web.

Meng, Y.H. et al. (2019) ‘Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia: a meta‑analysis’, Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 17(3), pp. 1611-1624.

Niznik, J.D. et al. (2020) ‘Risk for health events after deprescribing acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in nursing home residents with severe dementia’, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(4), pp. 699-707.

Orme, T., Guerreiro, R. and Bras, J. (2018) ‘The genetics of dementia with Lewy bodies: current understanding and future directions’, Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 18(10), pp. 1-13.

Pickett, J. et al. (2018) ‘A roadmap to advance dementia research in prevention, diagnosis, intervention, and care by 2025’, International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(7), pp. 900-906.

Safarpour, D. and Willis, A.W. (2016) ‘Clinical epidemiology, evaluation, and management of dementia in Parkinson disease’, American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 31(7), pp. 585-594.

Seppi, K. et al. (2019) ‘Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease—an evidence‐based medicine review’, Movement Disorders, 34(2), pp. 180-198.

Sheu, J.J. et al. (2019) ‘Association between anticholinergic medication use and risk of dementia among patients with Parkinson’s disease’, Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy, 39(8), pp. 798-808.

Silveira, C.R.A. et al. (2019) ‘Ambroxol as a novel disease-modifying treatment for Parkinson’s disease dementia: protocol for a single-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial’, BMC Neurology, 19(1), pp. 1-10.

Stinton, C. et al. (2015) ‘Pharmacological management of Lewy body dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(8), pp. 731-742.

Stoker, T.B., Torsney, K.M. and Barker, R.A. (2018) ‘Emerging treatment approaches for Parkinson’s disease’, Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. Web.

Tariq, S. and Barber, P.A. (2018) ‘Dementia risk and prevention by targeting modifiable vascular risk factors’, Journal of Neurochemistry, 144(5), pp. 565-581.

Terracciano, A. et al. (2017) ‘Personality traits and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia’, Journal of Psychiatric Research, 89, pp. 22-27.

Tewari, D. et al. (2018) ‘Ethnopharmacological approaches for dementia therapy and significance of natural products and herbal drugs’, Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 10. Web.

Tysnes, O.B. and Storstein, A. (2017) ‘Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease’, Journal of Neural Transmission, 124(8), pp. 901-905.

van der Lee, S.J. et al. (2018) ‘The effect of APOE and other common genetic variants on the onset of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia: a community-based cohort study’, The Lancet Neurology, 17(5), pp. 434-444.

Zeuner, K.E. et al. (2019) ‘Progress of pharmacological approaches in Parkinson’s disease’, Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 105(5), pp. 1106-1120.

Zucchella, C. et al. (2018) ‘The multidisciplinary approach to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. A narrative review of non-pharmacological treatment’, Frontiers in Neurology, 9. Web.