Abstract

The present topic considers the problem of inefficient depression management, which, given the significance of the condition, needs to be addressed. The problem is reviewed within specific settings as the project strives to answer the following PICOT question: in nursing staff at VEGA Medical Center (Miami, FL), how does the implementation of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] (2016a) guidelines affect the accuracy of the management of depression in the geriatric population within 8 weeks? VEGA is a primary care center, which had no specific guidelines on depression management before the project. As a result, it was running the risks of economic inefficiencies and decreased quality of care.

The project conducted a pilot change, which involved the introduction of NICE (2016a) guidelines into the practice of ten nurses from VEGA. The quality of their care prior to and after the intervention was evaluated with the help of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) quality standards, and interviews were conducted every week for formative evaluation. The results suggest that the quality of depression management can be improved by the guidelines and that the change was generally successful. Since the project is a pilot change, its primary implication consists of the fact that the guidelines can be employed by VEGA. Finally, the project offers some conclusions on the barriers and facilitators to change which may be of interest to healthcare professionals in general.

While it is a significant health concern that can notably affect the quality of life of patients, depression is not managed very effectively (Petrosyan et al., 2017). One of the issues that may be connected to this outcome is the fact that not every facility has direct guidelines which would facilitate depression management. The purpose of the present paper is to describe a project that piloted the use of depression management guidelines within specific settings. In particular, the nurses of the VEGA Medical Center (Miami, FL) were provided with the opportunity to integrate the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] (2016a) guidelines into their practice. The paper describes and demonstrates the significance of the problem, establishes the project’s PICOT and theoretical framework, and offers a synthesis of the literature on the topic to explain the choice of the intervention. Apart from that, the paper describes the settings and the project and conducts an evaluation of the latter. The discussion of the results and implications, as well as limitations and dissemination plans, is also present.

Significance of the Practice Problem

Depression is a significant and rather prevalent health concern (Duhoux, Fournier, Gauvin, & Roberge, 2012; Petrosyan et al., 2017). It tends to cause suffering and decrease the quality of life in patients and the members of their families; also, it can be related to increased mortality in patients and is typically associated with lower general health and income when compared to non-affected population (Duhoux et al., 2012; Petrosyan et al., 2017; Taylor, 2014). Moreover, healthcare costs are affected by depression, which is related to increased use of healthcare services (Petrosyan et al., 2017). The condition is also relatively prevalent: up to 16% of the US population aged 18 or older are reported to have experienced at least one major depressive episode (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [CBHSQ], 2016, p. 3054). Overall, it is apparent that depression is a national concern for the US.

Depression occurs in various populations, including the elderly: it can be a recurrent or chronic condition, but a late-life onset is also a possibility (Taylor, 2014). The percentage of the adults older than 50 years who have been diagnosed with a major depressive episode amounted to 4.8% in the US in 2015 (CBHSQ, 2016, p. 3055). Depression in the elderly is especially difficult to manage due to the specifics of the population: older people are more vulnerable and exceedingly likely to experience various medical conditions in addition to depression (Taylor, 2014). Thus, appropriate management of depression is crucial for the elderly population.

Unfortunately, depression management is not always efficient, which is a prominent quality of care problem. The recent studies by Petrosyan et al. (2017) and Straten, Hill, Richards, and Cuijpers (2015) describe this fact as a macro-level issue: they state that the detection and management of depression are currently not very effective throughout the world. Considering the problem, Straten et al. (2015) focus the inefficiencies in treatment, especially the situations in which some patients receive excessive services while others are under-treated. Obviously, this inefficiency may affect patient outcomes in the latter case, leading to less effective depression management (Belsher et al., 2016; Straten et al., 2015), which is a significant care quality issue.

On the other hand, the former case (excessive treatment) is not economically feasible (Aa et al., 2015). The latter issue is especially important for the US due to its continuously growing healthcare expenditures. Indeed, the US healthcare spending is currently greater than that of any other country, which does not necessarily get reflected in patient outcomes (Woolf & Aron, 2013). Therefore, the economic inefficiencies might also be associated with lower quality of care.

Multiple researchers agree that the problem of inefficient depression management needs to be addressed and suggest that it can be resolved with the introduction of clear guidelines and an effective framework for depression management (Aa et al., 2015; Belsher et al., 2016; Straten et al., 2015; Petrosyan et al., 2017). However, such guidelines and frameworks are not always present in healthcare facilities. Within the settings of the present project, no such guidelines had been implemented before, which, as shown above, may have negative quality and safety implications and can lead to inefficient spending.

Thus, the key problem that is considered in the present research is inefficient depression management, which is predominantly related to the quality of provided care. The significance of the issue is apparent due to the way it affects the lives of the patients, including the vulnerable elderly population, and the financial strain on healthcare that it causes, which the US should not have to afford. Given the prevalence of depression in the US, the improvement of the quality of care in its facilities is of notable importance, and the use of suitable guidelines seems to be an appropriate solution.

PICOT Question

The following PICOT question has been formulated for the project: in nursing staff at VEGA Medical Center (Miami, FL), how does the implementation of NICE (2016a) guidelines affect the accuracy of the management of depression in the geriatric population within 8 weeks?

The population in question includes the nurses of the VEGA medical center. The final sample consisted of ten nurses. The participants were included regardless of their gender, ethnic backgrounds, and age. Their experience and education did not affect the recruitment either. Technically, the inclusion criteria were the profession and the place of work of the potential participants.

The chosen intervention was the NICE (2016a) guidelines. They are evidence-based and updated; according to the AORN model for evidence rating, such guidelines can be viewed as sufficient evidence for a practice to be recommended (Spruce, Wicklin, Hicks, Conner, & Dunn, 2014, p. 253). The guidelines are very comprehensive, but they focus on the stepped care model, discuss the key aspects of caring for people with depression, and recommend specific evidence-based interventions. In general, the guidelines describe the process of working with patients with depression from diagnosing to their recovery. There are not enough articles that offer research on the implementation of NICE (2016a) guidelines, but there is extensive evidence which shows that various aspects of the practice are appropriate. The intervention had not been implemented at the VEGA Medical Center prior to the project.

The present project does not have a comparison group; it is a test of change. As a result, the project considered the pre- and post-intervention performance of the VEGA center nurses. The changes in the quality of depression management were viewed as the primary outcome of this project; the desired outcome was its improvement. The outcomes (as well as the pre-intervention quality of depression management) were assessed with the help of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] (2017) quality standards for depression management. They are very comprehensive and include multiple quality indices presented as percentages (for instance, the percentage of recommended decisions on patient care). The indices are organized with the help of thirteen statements. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] (n.d.; 2016b) claims that the standards are valid, which makes them an appropriate tool for the project. Also, the assessment is in line with NICE (2016a) guidelines for depression treatment; all the NICE (2016a) tools, which are included in the guidelines, refer to these standards.

The timing of the project is eight weeks, which proved to be enough for the key activities, including the introduction of the change, major assessments (pre- and post-intervention), and the measurement of the short-term outcomes. Naturally, a longitudinal study could provide some information on the long-term outcomes and sustainability, but the present study focused on the short-term ones. If deemed feasible by the organization, a follow-up project can be carried out in the future.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of the present project consists of several approaches to change management that are chosen to satisfy the varied needs of the project. Indeed, change management is a complex process, and the employment and integration of several influential models during it appears to be a reasonable decision. This idea is illustrated by Hanrahan et al. (2015) who develop a new framework that is based on the elements of multiple models, including the Iowa model, Rogers’ (2010) theory, and Cullen and Adam’s (2012) strategy.

Rogers’ (2010) Innovation Diffusion Theory, namely, its approach to innovation attributes is the first model that is employed by the present study to manage its change. This part of the theory considers the multiple perceived attributes of innovation, demonstrating their impact on the rate of adoption. The key attributes include aspects like the relative advantage of the new option as compared to its predecessor, the compatibility of the new option with the processes and characteristics of the settings (including cultural aspects), and its complexity (that is, the perceived difficulty of employing the new option). Apart from that, the ability to observe results of the change (observability) and test it (trialability) are important.

Roger’s innovation theory is not a nursing model, but it has been used by nurses in order to manage change at the individual level (Hanrahan et al., 2015). Indeed, Rogers (2010) suggests that by diagnosing and changing the perceptions of the adopters about a chosen innovation, a leader can increase the rates of individual adoption. Since it is essential for achieving organizational-level change (Pashaeypoor, Ashktorab, Rassouli, & Alavi-Majd, 2016), the management of individual-level change is viewed as the primary tool of ensuring the successful adoption and sustainability of the change.

Apart from that, Kotter’s (2012) change model is also used. It is another non-nursing theory that is well-established and frequently used, possibly, due to its attention to the preparation to change (Anders & Cassidy, 2014). This model is predominantly concerned with organizational-level leadership activities (for example, vision development and culture management). In particular, the eight steps of the model by Kotter (2012) require the development of a sense of urgency to engage and motivate human resources, the creation of the guiding coalition for management purposes, and the establishment of appropriate vision and strategy for the selected change. The latter are then communicated to the employees, who are empowered to bring down barriers and carry out the required change. In the process, short-term wins are highlighted and consolidated along with more long-term gains that should result in further change. Eventually, the change is to become rooted in the organization’s culture. Given the importance of leadership for successful change, Kotter’s (2012) change model appears to be important for the current study.

Finally, the two models are also incorporated into the Iowa Model of Evidence‐Based Practice by the Iowa Model Collaborative (2017), which will be discussed in detail in the project description section. The Iowa Model Collaborative (2017) regularly validates the model, and it is a well-established but recently-updated framework that was developed specifically for EBP introduction and that proved to be effective (White & Spruce, 2015). While the Iowa model is more detailed than those by Kotter (2012) and Rogers (2010), it does not directly include the suggestions on individual-change management the way Rogers (2010) does. Apart from that, while it is focused on EBP integration into practice (which is the goal of the chosen study), it does not include the recommendations on leading the change the way Kotter’s (2012) model does. However, as exemplified by the framework by Hanrahan et al. (2015), the Iowa model is capable of integrating multiple other theories and models. As a result, the current project intends to combine all the benefits of the three models.

In summary, the theoretical framework of the study integrates three major models, including one focusing on individual-level change and two that are predominantly concerned with organizational-level change. The contribution of Kotter’s (2012) model consists of leadership tools, and the Iowa model is specifically tailored for the introduction of EBP (Iowa Model Collaborative, 2017). As a result, the developed framework is comprehensive and enriched with multiple tools. The described models were chosen for their proven effectiveness (Anders & Cassidy, 2014; Hanrahan et al., 2015). As shown by Hanrahan et al. (2015), the introduction of multiple approaches to change management is sufficiently effective, even when the management of complex changes is concerned.

Synthesis of the Literature

The search that was performed for this project was not able to locate any articles that would specifically test the NICE (2016a) guidelines. However, the fact that the guidelines are rooted in evidence can be proven. First of all, NICE (2016b) states that all of its standards and guidelines are the result of a collaborative effort (shared by nursing colleges and organizations of the UK) that is aimed at synthesizing available evidence through research, discussion, revision, and validity checks. Thus, NICE (2016b) works to make its guidelines evidence-based. In turn, such guidelines are viewed by the nursing community as the evidence of very high level; such guidelines are sufficient for a practice to be viewed as recommended (Spruce et al., 2014, p. 253). Thus, it can be suggested that NICE (2016a) guidelines are evidence-based by virtue of being high-quality guidelines developed by the healthcare community of the UK.

However, additional evidence can also be provided. In particular, the specific aspects of the guidelines can be supported by the modern literature. The NICE (2016a) guidelines are very comprehensive, which is why it would be difficult to review all the evidence on every recommendation that it provides. As a result, for the current project, several aspects of the guidelines have been chosen to be considered from the perspective of the currently available literature.

An example of interventions that are recommended by NICE (2016a) is stepped care, which is an approach to care that prioritizes the employment of the most effective and evidence-based, as well as the least intrusive, intervention as the initial treatment and its substitution in the cases when it is not effective, or the patient does not want to use it. Straten et al. (2015) point out that this approach is supposed to be more effective and cost-efficient; technically, its development is a response to the existing problem of excessive and insufficient treatment which affects patients with depression nowadays. Trials indicate that stepped care can indeed resolve the issue of insufficient treatment in various populations, including elderly people (Aa et al., 2015; Belsher et al., 2016), although there is no sufficient evidence to claim that it tends to improve the cost-efficiency of treatment (Straten et al., 2015). When developing their systematic review, Straten et al. (2015) point out the fact that there is not much high-quality evidence on the use of stepped care in depression management, but the present information does suggest that it is beneficial for patient outcomes. Thus, stepped care can be viewed as a reasonable recommendation. It is also noteworthy that the above-mentioned articles support the idea that the introduction of clear and effective frameworks and guidelines can improve depression management.

Another recommendation that NICE (2016a) suggests is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), including cognitive therapy (CT). This approach to depression treatment is rather well-researched (Naeem et al., 2015), and finding high-quality articles on the topic is not difficult. For instance, Naeem et al. (2015) conduct an RCT to test the effectiveness of culturally adapted CBT and show that it is more effective than usual treatment and results in sustainable improvement in patients with depression. Also, Hollon et al. (2014) show that CBT enhances pharmacotherapy, increasing the rates of recovery for depressed patients, which is the goal of depression treatment. Driessen et al. (2013) also test CBT with the help of an RCT and show that it is effective in attaining remission and reducing symptoms. Thus, the existing evidence supports the approach.

Moreover, NICE (2016a) also recommends using intrapersonal therapy (IPT), and this approach is also sufficiently researched. For instance, Cuijpers, Donker, Weissman, Ravitz, and Cristea (2016) offer a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs on the topic and demonstrate that IPT’s effectiveness in depression treatment is notable; for example, when employed in subthreshold depression, it is capable of preventing major depression. Also, the authors highlight the fact that IPT is more effective when combined with other treatments (for instance, pharmacotherapy). Finally, IPT is shown to be more effective than treatment as usual in certain populations (for instance, women with chronic pain or earthquake survivors) (Jiang et al., 2014; Poleshuck et al., 2014). Thus, sufficient evidence supports this intervention as well.

In fact, there exist multiple trials that compare CBT or CT to IPT, and the majority of them find that the two are more or less similar in their effectiveness, which makes them interchangeable and appropriate alternatives that can depend entirely on patients’ preferences. Lemmens et al. (2015) compare the clinical effectiveness of the two approaches and find that both of them are effective in reducing the severity of depression. Lemmens, DeRubeis, Arntz, Peeters, and Huibers (2016) discover that the sudden gains prompted by the two approaches are comparable; in fact, CBT seems to have greater rates of sudden gains, but controlling for certain factors like the between-session intervals makes this change statistically insignificant. Thus, the evidence appears to predominantly suggest that IPT and CBT are more or less interchangeable.

However, Donker et al. (2013) compare specific interventions that are based on Internet platforms and find slightly different results. The authors demonstrate that two recently developed interventions (one based on CBT and one based on IPT), which are meant for self-treatment, are capable of reducing the symptoms of depression in patients, but CBT shows better results. It is noteworthy that this outcome is only applicable to self-guided and Internet-based specific interventions, which is why the results may be not very generalizable. Therefore, it is difficult to state that the article directly challenges the outcomes found in the works by Lemmens et al. (2015) and Lemmens et al. (2016). Still, it can be suggested that there is some contradicting evidence on the relative effectiveness of IPT and CBT, but both are proven to be effective in depression management.

A problem that was encountered during the search is the fact that few sources review the specifics of treating depression in the elderly population. The majority of sources specifically target the population between 18 and 65 years old, which may be prompted by ethical considerations. Still, the RCT by Aa et al. (2015) does specifically target older adults; the systematic review by Straten et al. (2015) includes four studies that target older populations, but they are not very recent. Also, Hollon et al. (2014) and Jiang et al. (2014) do not specify the age of the participants of their RCTs beyond stating that they are older than 18, and Cuijpers et al. (2016) report that their review focused on any age groups. Thus, there is some evidence which supports the employment of all the mentioned interventions in older populations, but this group of patients does not seem to be very well-researched.

With the exception of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses by Straten et al. (2015) and Cuijpers et al. (2016), the above-mentioned sources present the results of RCTs. Moreover, as can be seen in Appendices A and B, the majority of the sources also have rather large samples, employ well-established methods of data collection and analysis, and introduce methods of bias reduction like triangulation. It is also noteworthy that smaller samples are characteristic of the sources that review specific populations; for instance, Jiang et al. (2014) consider very specific patients, which is earthquake survivors with depression. Mostly, the samples exceed one hundred people. Both systematic reviews diligently describe their methodology, highlighting their triangulation procedures and the methods of determining the quality of studies. Thus, it can be suggested that the presented evidence is high-quality. As for the level of evidence, using the evidence pyramid described by Polit and Beck (2017), RCTs should be viewed as the evidence of the second level, and the systematic reviews are the evidence of the highest level. Therefore, the NICE (2016a) guidelines interventions are supported by the highest-level evidence.

In summary, no recent articles appear to test the NICE (2016a) guidelines, but their elements are supported by high-quality recent evidence, including RCTs and systematic reviews. Some inconsistent results also suggest that certain interventions may be more effective than other options as can be seen in the case of CBT and IPT: the former may be more effective than the latter. However, this evidence is inconsistent and appears to be applicable to specific interventions; CBT and IPT are mostly shown to be interchangeable and effective. Also, there appears to be a shortage of studies that would consider the elderly as their primary population, but a few studies do include some information on this group of patients. Finally, some of the studies demonstrate the fact that the introduction of clear frameworks and guidelines like stepped care, which is supported by NICE (2016a), can be beneficial for depression management. Thus, it can be suggested that modern literature supports the interventions proposed by the NICE (2016a) guidelines.

Practice Recommendations

The evidence provides some indirect support to the idea that the introduction of evidence-based guidelines can affect community clinic nursing staff, improving the accuracy of diagnosing and quality of managing depression in the older population, which is an answer to the PICOT question. No discovered evidence directly discusses the NICE (2016a) guidelines, but there is sufficient evidence which supports its interventions. In fact, the interventions appear to be relatively well-researched. The studies that provide this support include RCTs and systematic reviews with decent samples and consistent methodology. This evidence can be viewed as high-level and high-quality information, which implies that it is capable of supporting practice (Spruce et al., 2014, p. 253).

The majority of the statements produced by the evidence can be described as consistent. A minor discrepancy appears with respect to the comparative advantages of the two of the proposed interventions, due to which it is not apparent which one of them is more effective: CBT or IPT. However, the idea that both are roughly equal in their effectiveness appears to be dominant.

The majority of the studies, especially RCTs, purposefully avoid the elderly population, which slightly limits the applicability of the research to the patient population of interest. In general, when compared to the population aged 18-65, the elderly population appears to be understudied. Still, all the mentioned interventions are shown to benefit the elderly population in at least one study.

It is also noteworthy that several studies (those devoted to stepped care) comment on the fact that the presence of a clear framework for depression management is expected to be beneficial both for the patients and organization. Thus, the practice recommendation for modern healthcare organizations would be to adopt appropriate guidelines which promote evidence-based practice. NICE (2016a) guidelines correspond to these requirements, which means that the evidence supports the proposed intervention.

Project Setting

The present project took place at the VEGA medical center, which is located in Miami, IL. It is a primary care center that focuses on Family Medicine and Internal Medicine provided in a variety of settings from offices to hospitals. The vision of the organization is to build healthier communities, and its mission is to provide high-quality and affordable care. The key values of the company include innovation, which is in line with the project; the project is also aligned with the mission and vision because all of them aim at improving the quality of care.

The center celebrates diversity and promotes culturally competent care because VEGA serves a culturally and economically diverse community. Consequently, it is difficult to describe the typical patient of the settings. The elderly population of both genders may be prevalent because of various chronic illnesses that are treated by the center, but other age groups are also served by it. As a result, the project targets the population that is rather prevalent among the center’s patients.

The key decision-makers of the institution include the owner, medical director, and the administrator and manager, who comprise the bulk of the organizational structure of the center. The support of the administration was received in the letter of support. However, no financial support was provided for the project. The nurses of the center are included in decision-making, which is shared, and this factor facilitates nurse-led change. In general, the organization welcomes change due to its innovation value, although it is possible that a major innovation might meet some resistance due to the specifics of the change process (Hanrahan et al., 2015).

The process of needs assessment was carried out with the help of a discussion with the administration and the staff of the center. In particular, the administrator and manager of the center and two of the nurses agreed that the problem of the absence of direct guidelines on depression diagnosis could have detrimental effects on the quality of care. Also, one nurse suggested that it would be more convenient for the staff to have direct guidelines. Thus, the need for guidelines is recognized by the organization. Using the Iowa model terminology, this trigger is related to a problem (an absence of practice) (Brown, 2014), which can be resolved with the help of the NICE (2016a) guidelines.

The primary stakeholders of the project are the nurses of the VEGA medical center, their patients, and the organization itself. The absence of the standardized guidelines may complicate the treatment of patients with depression (Petrosyan et al., 2017), which is especially problematic for vulnerable populations like older adults (Taylor, 2014). Moreover, the nurse advisor from the VEGA center suggests that the existence of clear guidelines will make the process of depression management easier for the staff. Also, both these outcomes would be expected to lead to increased satisfaction in nurses and patients and better outcomes, which is beneficial for the company and its reputation. Finally, the standardization of the guidelines improves the cost-effectiveness of service, which is beneficial for the organization (Duhoux et al., 2012). Thus, multiple stakeholders will benefit from the change.

The innovation is expected to be sustainable since it presupposes the change of the center’s policy with respect to depression management. The adaptation of the change to the needs of the organization and the routinization of the guidelines was supported by the tools suggested by the theoretical frameworks, including those by Kotter (2012) and Rogers (2010). After the project, the nursing leaders and the administration will ensure the sustainability of the change. No unexpected consequences are likely to occur because of the implementation of an EBP guideline, and it poses no danger. The only possible risks may be connected to the resistance to change or ineffective use of the guidelines, which might affect the outcomes.

A SWOT analysis of the project is presented in the form of a table in Appendix C. It demonstrates that the key strength of the project is the evidence-based intervention that can address the problem of the organization, and the weaknesses are related to the restricted time (see Appendix D) and budget. The organization provided the opportunities, which the project employed, including the support of the stakeholders. However, the project also recognized the fact that there was a possibility of resistance to change and inefficient employment of the guidelines. The former issue was addressed with the help of the theoretical frameworks (especially Rogers’ (2010) theory), and the latter was mitigated with the help of formative assessments.

Project Vision, Mission, and Objectives

The vision of the project is the optimal quality of the management of depression in the older patients of the VEGA medical center. Its mission is to improve the quality of depression management of the VEGA center by providing its nurses with the guidelines that can help them to achieve this outcome. It is apparent that the project is in line with VEGA’s vision and mission. As it was mentioned, VEGA is a medical center that aspires to improve the health of the community, and its mission is high-quality and affordable care. The promotion of evidence-based practice is likely to improve the quality of depression management and, therefore, the health of the community, and the employment of care standards can have a positive impact on the costs of care (Petrosyan et al., 2017).

For the objectives of the project, the SMART framework is used: it involves the consideration of the “specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and timely” objectives (Murray, 2017, p. 347). Two long-term objectives are proposed to prove the adoption of the guidelines and measure their effects.

- At the completion of the project (week eight, timeframe), all the adopted quality indicators suggested by NICE (2017) will experience improvement (specific, realistic, achievable) as evidenced by the depression case management documentation (measurable).

- At the completion of the project (week eight, timeframe), all the participants will report being able to apply the new guidelines as evidenced by the documentation of the final discussion with them (specific, realistic, achievable, and measurable).

Short-term objectives are the following ones.

- During the first week of the project (timeframe), 100% of the nurses will review and understand the new guidelines as evidenced by their reports during the discussion of the first week (specific, realistic, achievable, and measurable).

- At the beginning of the second week of the project (timeframe), 100% of the nurses will be using the new standards (specific, realistic, achievable) as evidenced by their use of depression case management documentation (measurable).

- By the fifth week of the project (timeframe), at least 50% of the nurses’ reported concerns and difficulties will be addressed (specific, realistic, achievable) as evidenced by the discussion documentation (measurable).

The project aims to improve the quality of care, but it is acknowledged that this outcome may be not achieved. Thus, the unintended consequence of the project is the lack of improvement. Moreover, the change is a complex process, which might cause short-term confusion and decrease in the quality of care. Also, the change might put additional pressure on nurses, which may also affect their productivity in a negative way and, possibly, discourage them from employing the new methods. All the stress-related risks and unintended consequences were mitigated with the help of active communication and the project’s theoretical and practical change models.

Project Description

Chosen Change Model

The present study uses the Iowa Model of Evidence‐Based Practice as its primary guide because this model is well-established and tested and was developed specifically to introduce evidence-based practice into clinical settings (Iowa Model Collaborative, 2017; White & Spruce, 2015). The most recent validation study was carried out by the Iowa Model Collaborative (2017) between 2001 and 2013 to gather the feedback of users, and the present study employs the version of the model that was established as a result of this research. The model includes seven key steps along with multiple sub-activities for four of them; apart from that, it is non-linear and includes several points of decision-making. The present section will focus on the key steps while discussing the decision-making activities when possible.

Pre-design Activities

According to the Iowa Model Collaborative (2017), four steps are carried out before the EBP introduction project is designed. First, the issues or opportunities are determined. To this end, the needs assessment activity was carried out, which involved discussions with the administration of VEGA, as well as its staff. The outcomes demonstrated that the mentioned groups acknowledge the issues that can be connected to the lack of appropriate guidance on depression management. A nurse also pointed out that the presence of guidelines should facilitate depression management and be more convenient for the nurses. Thus, the triggering issue (the lack of guidance) and potential opportunity (the introduction of high-quality, evidence-based guidelines) were determined and identified as a priority. Apart from that, this stage includes the beginning of data assemblage, and during this step, it was determined that the NICE (2016a) guidelines are the ones that are most likely to fit the project.

The next step typically consists of forming a team. Since the change was a small-scale one, its team consisted of the primary investigator and one of the administrators of the VEGA center who was predominantly concerned with piloting and sustaining the change. After the team is formed, the work with the evidence begins. The literature review above and the evidence tables in Appendices A and B indicate the outcomes of this step. As a result of the investigation, it was determined that there is sufficient high-quality data to indicate that NICE (2016a) guidelines are evidence-based, which implies that they are appropriate for the change. After confirming the presence of sufficient evidence to support the desired change, the principal investigator proceeded with design activities.

Design Activities

In accordance with the recommendations that are based on researched evidence, the change that is described in this section is concerned with the introduction of NICE (2016a) guidelines into the practice of the nurses of the VEGA Medical Center. The design activities include planning, participant engagement, pilot change, and evaluation; the latter step can result in redesigning (Iowa Model Collaborative, 2017). The planning of the project involved the consultations with the settings’ administration, as well as the feedback solicited by the principal investigator from multiple sources. The project consists of a pilot change: that is, it introduces the new guidelines for a limited period of time (eight weeks) and small sample (ten nurses). The design of the project can be described as a pre-test and post-test study: it included the collection of data before the introduction of NICE (2016a) guidelines and after it to determine the impact of the latter on the quality of care provided by VEGA’s nurses. The specific activities that were carried out during this step can be described as follows.

The recruitment of the nurses, which was carried out with the help of flyers, was the first step. The response rate amounted to 100%, and all the ten nurses agreed to participate as was anticipated. Thus, the sample of the project amounted to ten nurses of the VEGA center. The nurses were provided with the copies of consent forms, which they signed during the first day of the first week of the pilot change. After that, a meeting was carried out with all the nurses, during which they were provided with all the required materials and instructions regarding the use of NICE (2016a) guidelines. No criticisms were suggested during this discussion; the nurses approved of the proposed guidelines. Apart from that, during the first week, the information about the nurses’ performance was analyzed and relayed with the help of the project’s data collection tool: the NICE (2017) quality standards.

Throughout the pilot change, the nurses were required to proceed with their duties as usual while also using the NICE (2016a) guidelines and NICE (2017) quality standards to document their performance (see Appendix E). Apart from that, every week, they were required to attend a discussion for formative assessments; the latter took the form of a focus group interview (see Appendix F). It was assumed that the meetings could provide the data for redesigning if necessary (Iowa Model Collaborative, 2017), but the outcomes of the discussions did not indicate major problems with the design. Both NICE quality standards and meetings were employed for data collection. At the end of the pilot change (during week eight), the nurses submitted their reports to the principal investigator. After the end of week eight, the data were gathered, cleaned, and analyzed. The quantitative data were processed statistically with the help of sign test, and qualitative data were analyzed thematically. The results of the project are being reported by this paper.

Throughout this step of change management, the project also employed the tools proposed by Rogers (2010) and Kotter (2012). In particular, the participants were being engaged in order to communicate the project’s vision, mission, and strategy, as well as to gather and manage their perceptions of the change. These activities were carried out with the help of the weekly meetings mentioned above. Thus, the promotion of adoption, which is a part of the Iowa model, was carried out throughout the project as well with the help of the instruments promoted by the models that are included in the theoretical framework of the project. Overall, the project covers all the required elements described by the Iowa Model Collaborative (2017) as a part of the pilot change.

Sustaining the Change and Disseminating the Results

The Iowa Model Collaborative (2017) views the efforts of sustaining the change as the sixth step of EBP introduction. The final part of the Iowa model consists of disseminating the results. In the present project, results dissemination is viewed as another form of change-sustaining activities; in particular, in accordance with Kotter (2012), it is considered to be a demonstration of short-term wins. Kotter (2012) believes that the dissemination of wins proves the effectiveness of change and improves motivation, which is in line with Rogers’ (2010) idea of the trialability of change. A change with trialability is trusted more (and, therefore, easier adopted) because the opportunity to trail it provides the adopters with the data about it and the actual results that can be observed. The results can also be used to prove multiple attributes of the innovation like its advantages and compatibility, which modifies the perceptions of the adopters.

Dissemination is the final activity that the principal investigator is going to conduct. The rest of the sustainability activities, including the integration of the new guidelines into the center’s culture, are going to be carried out by the nurses and administration. Similarly, the decision to proceed with the change is going to be made by the mentioned stakeholders. However, it should be pointed out that throughout the project, efforts to ensure sustainability have been present. They will facilitate future change should VEGA proceed with it.

Indeed, the above-mentioned discussions carried out this function as well: as recommended by Rogers (2010), they focused on the perceptions of the nurses to ensure that their understanding of the change is correct, and they provided an instrument for modifying the perceptions if required. Apart from that, the discussions were an engagement, communication, and empowerment tool: they provided the nurses with an opportunity to reflect on the barriers and facilitators, offered support, and communicated the vision and strategy of the project, equipping the participants to proceed with the change. All the mentioned activities are based on the ideas of Rogers (2010) and Kotter (2012). It is also noteworthy that, as it was mentioned, the project is generally in line with the organizational culture, which should facilitate the final step promoted by Kotter (2012): the integration of the change into the culture of the settings. Thus, the project has promoted sustainable change, and if VEGA chooses to proceed with it, it will enjoy the positive outcomes of these activities.

In summary, the chosen theoretical framework and the primary change model have provided the nurses with the tools and guidance that are necessary for completing the project. The Iowa model offered the primary framework that incorporated all the key activities of the project while the theory of Rogers (2010) and the model of Kotter (2012) introduced more specific details and guidance related to the management of individual-level change and leadership activities.

Timeframe

The timeframe of the project includes all the elements that are suggested by the Iowa Model Collaborative (2017) with the exception of sustainability and dissemination activities. As can be seen in the Gantt chart presented in Appendix D, the pre-implementation activities included the development of the project proposal and IRB proposal, as well as their submission. During the development of proposals, planning activities also started. The implementation activities began after the IRB had reviewed and approved the proposal; they included the recruitment of participants (complete with informed consent procedures), formative and summative assessments, and data collection (including baseline and post-implementation data collection). The implementation of the project (which can be described as a pilot change) took eight weeks. After that, the data collection procedures were finalized, and their analysis was followed by the evaluation of the project. Eventually, the report was developed and submitted.

The timeframe includes three continuous elements: literature research (evidence collection and assessment), meetings with faculty and preceptor, and feedback solicitation. All these activities enabled the rest of the project’s steps by providing it with the data and critique necessary for progress and improvement. Finally, it is also noteworthy that most of the activities overlap, which the Gantt chart attempts to illustrate (see Appendix D). While initially considered a potential constraint, the timeframe fit the project due to careful planning and time management, as well as the cooperation of the participants. In particular, the results of the discussions indicate that eight weeks were enough to test the guidelines and make a decision regarding their usefulness. As for the time allocated to the data analysis and evaluation, it also proved to be sufficient.

Required Resources

The budget of the project can be seen in Table 1. The anticipated costs were notably greater than those that actually were required as can be seen in the initially prepared billing and the eventual difference between expenses and revenue. The project involved the costs of hiring a statistician to ensure the high quality of statistical analysis and the expenses related to printing some of the materials (guidelines and decision-making flowcharts). The project was not supported financially, but VEGA has enabled it from multiple other perspectives.

Indeed, space for the project’s procedures was provided by the center; also, the human resources were organized with the help of VEGA. The administration provided the equipment that the nurses used for reporting (mostly, computers), and the nurses employed their personal devices (mobile phones) to keep in contact outside of the weekly meetings. The administration received no remuneration for their support with the scheduling of the participants, and the participants themselves had no financial incentives. Participants dedicated particularly large amounts of time and effort to the project: they were required to adopt the guidelines, participate in weekly meetings that usually took about one hour, and report their performance with the help of the new reporting system. The primary investigator can be viewed as another person who dedicated a notable amount of time and effort to the change. Thus, human resources can be viewed as the primary ones that were employed by the project.

The project involved the review of evidence on the topic, which was carried out by the principal investigator and required the access to relevant literature. Also, the primary investigator employed personal devices (computer and mobile phone) to gather evidence, analyze it, and present the results. Other materials employed by the project included those provided by NICE (2016a): the guidelines, quality standards, and all the related materials (in particular, decision-making flowchart) are freely available online, and the permission to use them for the project was obtained. Thus, the majority of the project’s needs were satisfied either through free materials or enthusiasm and support of stakeholders, which explains its low costs.

Project Setting: Barriers and Facilitators Analysis

The analysis of the project settings is present above, but the following specifics were significant for the project execution. As it was established, the VEGA Medical Center needs the project and it also appropriate for the chosen change due to the specifics of the provided services and served population. Apart from that, the settings offer a number of facilitators for the change. First, the organizational culture is beneficial for the project since their values and strategies are aligned with each other. Second, the support of the stakeholders was determined during the needs assessment procedures and proven throughout the project by the enthusiasm of the nurses and the willingness of the administration to cooperate. In particular, the administration has provided the project with space for all the relevant procedures (obtaining consent, conducting meetings) and assisted with the management of the schedules to enable the meetings. Thus, the project’s settings provided some notable bonuses.

Some barriers can also be mentioned. In particular, the timeframe and budget were viewed as potential issues, as well as the resistance to change and inefficient adoption of the guidelines. Here, it should be mentioned that the project proved to be less costly than anticipated, and the assistance of the Center with rooming and materials distribution can be viewed as a factor that assisted in reducing the costs. The timeframe proved to be sufficient as well, possibly, due to the cooperation of the nurses and the help of the administration in scheduling activities. It is difficult to ensure that the guidelines were adopted and employed efficiently, but it can be suggested that the meetings must have had a positive impact on the process. Finally, there was no resistance to change, which may be attributed to the nurses’ enthusiasm, administration’s support, and the activities that were carried out to assist the adoption of the guidelines.

It can also be suggested that the lack of the resistance to change might have been connected to the fact that the chosen intervention is based on evidence that was gathered, analyzed, and synthesized through a collaborative effort of reputable healthcare organizations, which is true for NICE (2016a) guidelines. Apart from that, the change contributed to the resolution of a workplace issue that nurses and administration have been acknowledging. Thus, the mentioned strengths of the project have also helped to eliminate the threat of change resistance. Both facilitators and barriers are included in Appendix C in the form of a SWOT analysis. As can be seen from it and the above-presented analysis, the interrelationships between the strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats were to the benefit of the project: the former two were used to mitigate the latter two.

Principal Investigator’s Role

For the present project, my activities as the principal investigator are central because of the multiple roles that I have played. Throughout the project, I acted predominantly as a researcher. I collected evidence on the topic of depression management, performed a needs assessment at the VEGA center, searched for and found appropriate guidelines for the settings to use, and analyzed and synthesized the available information regarding depression management to prove their appropriateness. Apart from that, I designed the project. All the mentioned activities required the application of my skills and knowledge as a clinical scholar, which is one of the roles that a Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) can play (Wilkes, Mannix, & Jackson, 2013). Some of the pertinent competencies include the use of information technology to find evidence, the knowledge of research methodology, and the use of pertinent evidence evaluation models to select the high-quality research; the present study employed the AORN model for evidence rating (Spruce et al., 2014).

Moreover, during the implementation of the project, I needed to be a leader and educator, which are also relatively typical roles for a DNP (Blush, Mason, & Timmerman, 2017; Sherrod & Goda, 2016). In particular, I was required to ensure the nurses’ understanding of the chosen guidelines by training them to use NICE (2016a) tools, and I was required to engage all the stakeholders. My education prepares me for all the mentioned roles by ensuring that I am equipped with relevant knowledge and skills (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2006). Apart from that, I have had some experience with all the three roles, which facilitated the key activities that the project required of me. Finally, the chosen change framework incorporated the leadership suggestions by Kotter (2012), which helped me to apply my interpersonal and strategic thinking skills. Overall, the success of the project depended to a notable extent on my competencies, but I was equipped for the challenge and employed it to improve my skills.

Project Evaluation Results

Human Subjects: Recruitment, Protection, Concerns

The human subjects of the project included ten nurses. They were recruited based on their place of work: only the nurses from the VEGA Medical Center were included. The exclusion criteria that were considered involved the factors that could make the participants vulnerable: age and reduced language skills, as well as potential dependence on the principal investigators. However, all the nurses of VEGA are older than 18 and younger than 65, none of them has limited knowledge of English, and none of them depends on the investigator, which is why no exclusion criteria were eventually applied. The recruitment materials took the form of flyers that included the key information about the project and were distributed at VEGA. 100% of the nurses responded to the recruitment effort and agreed to participate. The recruitment procedures were finalized during the first week of the implementation process (see Appendix D).

The risks of participation have been classified as minimal. In particular, it has been acknowledged that change can be stressful and that during the interviews, nurses might experience some form of discomfort as a result of questions. Regarding the change, the employment of the above-mentioned framework, especially Rogers’ (2010) theory, was meant to assist the nurses in adopting the change more successfully. As for discomfort, the interview guides contain no questions that would be considered invasive, but it was still clearly communicated to the nurses that they do not have to respond to any question. This information was repeated at the beginning of every interview as a part of the introduction to the discussion (see Appendix F). The benefits of participation included the introduction of a helpful tool that can guide the process of depression management; as was established, it can facilitate the activities of nurses and assist them in improving the quality of their care. Thus, it can be suggested that the benefits are more significant than risks.

The participants’ anonymity and confidentiality were preserved. The nurses’ personal information was never collected; their data were coded with numbers, which were also used for the transcripts of the interviews. Thus, the nurses were anonymized. It is also noteworthy that no identifying patient data were ever provided to the principal investigator either; only the nurses managed the patient data, and they submitted the reports that did not have any identifying patient information in it. The NICE (2016a) guidelines focus on the performance of nurses, including, for instance, the specifics of the procedures and the appropriateness of chosen treatments (see Appendix E), which is why identifying patient data were not needed.

All the data, including the interview transcripts and the reports on performance that were submitted by the nurses, will be stored in a safe location for seven years as recommended by the IRB of the principal investigator’s educational institution. No one but the principal investigator will have access to it. Finally, the nurses were only recruited after they had signed a consent form which specified all the details of the project, related risks and benefits, and their rights as participants. It was specifically stated in the informed consent forms that the nurses could refuse to participate without any consequences. No remuneration was offered to the participants. In summary, the key ethical considerations pertinent to the project were reviewed and sufficiently addressed (Polit & Beck, 2017). The project was approved by the IRB of the educational institution of the primary investigator, and the implementation was only carried out after the approval was received.

Evaluation Design

The project employed two key tools for data collection. The first one is the NICE (2017) depression management quality standards that have been transformed into a data collection tool that fits the project. In particular, the principal investigator removed the quality standards that could not be applied to the project, for example, because they could not fit into the timeframe or because the data were not available (see Appendix E). Eventually, the project employed a tool with 10 applicable standards, one of which has two evaluation criteria (the rest have only one). This tool produces ratio data because it organizes the information into percentages. For instance, Quality Standard (QS) 1 indicates the percentage of assessments that were carried out by the nurse in accordance with NICE (2016a) guidelines. Since NICE (2017) standards are connected to NICE (2017) guidelines, they can provide strong evidence to the latter being adopted. As for the standards’ ability to measure the quality of care, they are evidence-based and have been developed by multiple professional organizations (NICE, 2016b). NICE (2016b) does not specify the reliability and validity scores for the standards, but they are still reported to be reliable.

NICE (2017) standards have been employed during the first and last (eighth) week of the project implementation. The nurses reported their performance with the help of these standards, using the existing records for the baseline data and the new ones for the post-implementation data. Therefore, it can be suggested that both secondary and primary data were used. As for the interviews, they employed a specifically-developed interview guide (see Appendix F). The process of its development involved a pilot interview with feedback from people with some experience in conducting group interviews. The interviews were carried out each week; transcripts were used to collect the data. This tool produced qualitative data.

Summative Evaluation

Summative evaluation (that is, the evaluation of the outcomes of the project) was carried out with the help of the NICE (2017) standards, which specified the eleven evaluation criteria that were supposed to exhibit improvement as suggested by the first long-term objective of the project. In order to enable this evaluation, baseline and post-intervention data were collected. The resulting quantitative data were analyzed statistically by a hired statistician. It should be pointed out that two different tests were employed. Given the specifics of the data (ratio with non-normal distribution) and sample (small group, the performance of which was measured twice to be compared), a non-parametric alternative to paired t-test was required (Polit & Beck, 2017). Also, the differences in the paired results were not symmetrically distributed, which is why sign test was used for them. Sign test can work with non-symmetric differences in paired data while also being a non-parametric alternative of paired t-test (Frey, 2018; MacFarland & Yates, 2016; Pett, 2016). Thus, the chosen tests fit the results of the project.

Initially, the project intended to distinguish no extraneous variables since it was difficult to determine a variable that would prevent nurses from complying with the guidelines. However, the discussions with the nurses indicated that the reason for non-compliance could be tied to certain aspects of depression management that have been noted by NICE (2016a) as well, including patient preferences for treatment and the choice of treatment based on the patient’s history. Some of the quality standards (QS 6-8) do not take into account these features, demanding a specific type of treatment for certain types of depression. As a result, the cases when specific factors demanded non-compliance were classified as appropriate depression management in the performance assessment documentation based on the nurses’ arguments.

The data were cleaned and combed through visual checking to ensure the absence of wild codes and incorrect outliers (Polit & Beck, 2017). Only one instance of missing data occurred; in particular, two of the nurses had no new assessments carried out by the end of the project. This issue was outside of the participants’ or principal investigators’ control and could not have been prevented. The two cases were deleted, and the remaining data were used for the project, which is one of the most common approaches to dealing with missing data (Kang, 2013).

Formative evaluation

The interviews, although multifunctional, were carried out predominantly with the aim of formative evaluation: a continuous review of the project’s progress with attention paid to the participants’ feedback (Duffy, 2016). The key criterion coincides with the project’s second long-term objective: the nurses’ ability to employ the guidelines is to be evaluated. Apart from that, to provide more specifics to this criterion, the difficulties, concerns, barriers, and facilitators associated with the guidelines were considered. Since this tool produced qualitative data, a common approach to its analysis was chosen: the thematic analysis. The latter involves searching for recurring patterns (themes) in the data, which are employed to make sense of the presented information (Polit & Beck, 2017). The tool also excludes the possibility of missing data, but to clean the latter, consistency checking was carried out. The results of both summative and formative evaluations are presented below.

Data Analysis

All the ten nurses have remained the participants of the project throughout it; at the beginning of the project, they were working with 188 eligible patients (older people with depression), and by its end, they were working with 200 eligible patients (see Figure 1). Tables 2 and 3 present the results of the measurements with respect to each of the quality standards. The cases of missing data are shown in it as well. The average results of the all the nurses with respect to every of the quality standards can also be seen in Figure 2. From the tables and figure, it is apparent that the majority of the performance indicators exhibit improvements with the exception of the indicators that showed 100% compliance since the beginning of the project.

There are three such indicators: QS 3, which is concerned with recording health outcomes, QS4, which is concerned with the use of low-intensity psychotherapy for mild and subthreshold depression, QS5, which is concerned with the use of pharmacotherapy for mild or subthreshold depression, and QS 12, which is concerned with the revision of the treatment for the patients who exhibit no response to initial treatment. In other words, all the nurses of VEGA have been using the recording approaches that are comparable to those promoted by NICE (2016a), have been managing mild depression in accordance with the principles comparable to those of NICE (2016a), and have been ensuring the revision of the treatment for non-responsive cases in a way that is approved of by NICE (2106a). Since no changes could have been exhibited by these standards, they were not analyzed statistically.

The results pertinent to the remaining quality standards have been analyzed with the help of sign test (see Table 4). The results indicate that only the changes pertinent to QS1, QS2a, and QS11 are statistically significant (p<0.05). In other words, as a result of the introduction of the guidelines, the nurses have started to assess depression in accordance with NICE (2016a) guidelines (QS1), prescribe the treatments that are suggested by the NICE (2016a) guidelines (QS2a), and monitor the patients who receive only pharmacotherapy in accordance with NICE (2016a) guidelines (QS11) more frequently. Figures 3, 4, and 5 illustrate the changes in the results related to QS1, QS2a, and QS11 respectively. The rest of the standards (QS2b, QS6, QS7, QS8) did not experience the statistically significant changes, but they increased nonetheless. The first standard describes the length of treatment, and the remaining ones are concerned with the use of specific treatments for specific subtypes of depression.

In summary, the results of the summative evaluation suggest that there has been some improvement in the performance of the nurses as measured by NICE (2016a) quality standards, and some of these improvements have been statistically significant. Therefore, the PICOT can be answered as follows: in nursing staff at VEGA Medical Center (Miami, FL), the implementation of NICE (2016a) guidelines within 8 weeks affects some of the aspects of the accuracy of depression management in the geriatric population in a positive way.

By the end of the project, 100% compliance with the NICE (2017) quality standards was achieved. Here, it should be highlighted that not all the treatments that were not in line with NICE (2017) quality standards were changed; reasonable non-compliance was allowed. In other words, with the exception of reasonable non-compliance, the nurses of VEGA have managed to achieve 100% compliance with the new quality standards. Reasonable non-compliance is in line with the NICE (2016a) guidelines, which are more flexible than the standards; therefore, when the guidelines are considered, the achieved compliance is also 100%.

The statistically significant changes predominantly indicate the aspects with respect to which the nurses of VEGA used to underperform when assessed with the help of the NICE (2017) quality standards. The latter factor is important since NICE (2017) only presents one version of such standards. They may be rather rigid, even though this rigidity is not reflected in the guidelines; the latter are sufficiently flexible to explain the reasonable non-compliance cases. Thus, the rigidity issue was controlled by introducing the reasonable non-compliance variable. Moreover, the fact that the nurses were able to revise at least some of the treatment plans indicates that they used to be insufficiently effective and required change (for example, due to inadequate response to said treatment). It is also possible that the revisions were carried out naturally in the case of inadequate responses of the patients; as can be seen from the results, the nurses of VEGA have always performed perfectly well when the revision of treatment is concerned. However, the fact that the changed treatments are in line with NICE (2017) seems to support the idea that the latter proposes adequate guidelines and standards.

The results of the formative evaluation can be summarized as follows. Due to the format of the interview, the discussions most often produced unanimous statements, although in some cases, differences were also notable. All the nurses have approved the guidelines, characterizing them as “appropriate,” “practical,” “convenient,” and “helpful.” By the end of the project, all nurses also reported being able to employ the guidelines; in particular, they stated that the guidelines were “understood” and “practically applicable.” Thus, based on the evaluation criterion described above, the project can be viewed as successful. No major issues were noted by the end of the project. However, throughout the project, some issues and difficulties have been mentioned.

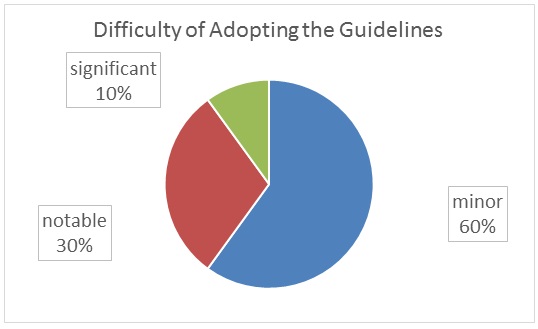

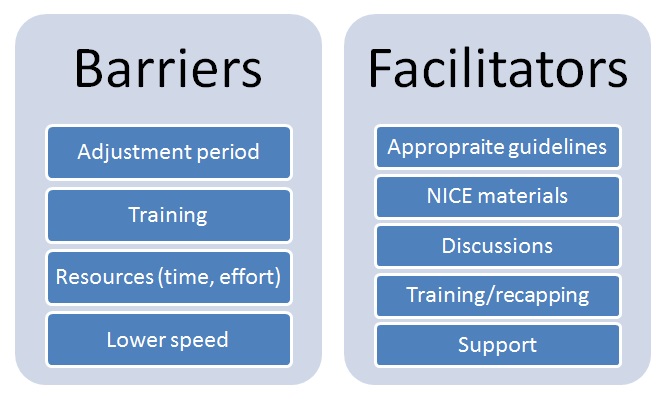

The primary issue proved to be the reduction of the speed of work, which was associated with two other factors that the nurses classified as barriers: the adjustment period (“getting used”) and training (“learning to use”). Apart from that, the issue of lower speed resulted in the resources barrier, which was concerned with efforts and time required for the project. However, the nurses acknowledged that these factors are typical for any change. When asked to rate the difficulties experienced by them with the help of a three-point scale (minor, notable, and significant), the majority of nurses (six) described the issues as minor (see Figure 6). Three nurses classified the mentioned problems as notable, and two nurses considered them significant.

The discussions were unanimously characterized as a facilitator. Throughout the discussions, the nurses were provided with educational support. Moreover, the nurses also reported feeling emotionally supported by their peers. The nurses pointed out that the discussions ensured timely feedback on issues, and they also suggested that the opportunity to speak about problems is emotionally helpful. The participants concluded that the discussion of a shared experience helps to process the latter.

Other facilitators were also noted. The fact that the proposed guidelines were perceived as “appropriate” was agreed to be one because it assisted the nurses in the adoption process. In this respect, the nurses stated that the guidelines were in line with their training and experience, which made the adjustment period easier. The materials provided by NICE (2016a), in particular, the decision-making flowchart, were also classified as helpful. The recapping that was proposed by the nurses and ended up being carried out almost every discussion was also viewed as a facilitator. Finally, the support of the management was considered an enabler since it ensured the possibility of the project. All the barriers and facilitators are summarized in Figure 7. In summary, the formative evaluation did not just provide some evidence to the project being successful; it also captured the development of the project along with the issues that could have prevented its success and the factors that might have enabled the latter.

Discussion and Implications for Nursing and Healthcare

100% compliance with the NICE (2017) standards (with the exception of reasonable non-compliance) seems to indicate the project’s success. With respect to some of the factors, including health records and subthreshold and mild depression treatment, the nurses have been performing excellently from the perspective of NICE (2016a) since before the project. Overall, the statistically significant improvements were only observed in assessment and monitoring procedures, as well as the overall choice of treatment for all the possible depression types (three quality indicators out of eleven). Thus, the introduction of the guidelines did not result in notable changes with respect to the majority of applicable quality standards predominantly because the performance of nurses could be classified as perfect or very high at the beginning of the project (see Tables 2-3).

However, the introduction of the guidelines can also be viewed as successful as a result of the formative evaluation. Indeed, when discussing the outcomes with the nurses, it was established that the NICE (2016a) guidelines were viewed as helpful and useful by the nurses. While some of the issues that can potentially disrupt a change process were experienced, the facilitators of the project were employed to mitigate possible difficulties. As a result, by the end of the project, the nurses reported their ability and willingness to use the guidelines, which implies that the change was successful and achieved its aim of providing the nurses with the means of improving, maintaining, and monitoring the quality of their care.

Other outcomes of the project that are worth discussing include the demonstration of the barriers and facilitators that can affect a similar change process. In particular, the barriers apparently incorporate those related to training and the adjustment period, and they can affect the speed of the nurses’ work, resulting in resource shortage, especially when time is concerned. However, educational efforts and materials, as well as support, can reduce these issues. Moreover, the nurses demonstrated the importance of managing their perceptions by indicating that the perceived “appropriateness” of the guidelines was helpful during the adoption process. This feature proves the significance of employing Rogers’ (2010) theory or another model that would consider the individual-level adoption process. Finally, the nurses made multiple positive comments regarding the use of the discussions, which proved the significance of offering change stakeholders an opportunity to provide feedback.

Several limitations and threats to the internal validity of the project can be noted. The validity and reliability of the two tools of the project are not very clear. NICE (2016b) states that all its materials are reliable and valid, but the NICE (2017) quality standards have no direct reliability and validity scores mentioned. The interview guide was developed specifically for the project, and it was not tested. Also, the rigidity of the NICE (2017) quality standards was noted by the nurses, but this problem was managed by introducing and controlling the reasonable non-compliance extraneous variable, which improved the project’s internal validity.

Moreover, the project is limited by its sample size, but it should be pointed out that as a pilot change, it is meant to focus on small-scale innovations. Apart from that, the small size implies that the results may be predominantly applicable to the project’s settings and cannot be generalized. The latter factor is not a problem since a pilot change is expected to make predictions for its settings. Finally, the fact that the nurses were reporting their results personally without providing access to the patient data to the principal investigator implies the potential for bias or incorrect reporting. The issue has been mitigated by ensuring confidentiality and anonymity; also, the nurses are interested in producing correct results since the aim of the project consists of testing a tool that may later be introduced in their working process. Thus, the limitations of the project are connected to the specifics of its design and are mitigated wherever possible. Still, they should be taken into account when reviewing the implications of the project.

The implications of the project and its evaluation are as follows. First of all, the results can be used to suggest that the NICE (2016a) guidelines can indeed improve the quality of depression management at least with respect to some parameters in the nursing staff of the VEGA medical center. Apart from that, the results indicate that the guidelines can be helpful from the perspective of the nursing staff of VEGA. Therefore, the recommendation to proceed with the change seems reasonable. Also, the project’s results imply that when proceeding with the change, it is necessary to pay attention to the key barriers and facilitators, providing the nurses with educational opportunities, support, and feedback options. These findings are in line with other studies that consider change (Hanrahan et al., 2015; Kotter, 2012; Rogers, 2010), and they may be significant for nursing practice and healthcare. Still, the implications of this pilot change are predominantly significant for the microsystem and may be not applicable outside of the settings. Also, if a more appropriate tool for quality assessment can be found, it should be employed in future research to produce more precise and generalizable results.

Plans for Dissemination

The Iowa Model Collaborative (2017) views dissemination as the final element of its model, but since the project is a pilot change, the reporting of post-pilot data step is more applicable. In any case, as pointed out by Kotter (2012) and Rogers (2010), the observation of the results, which indeed can be classified as short-term wins, is particularly important for the sustainability of an innovation. Therefore, the decision to present the results to the stakeholders of the change was made. The presentation focused on the evaluation part and had motivational and relatively informal features. All the key stakeholders were invited (management and nurses). Copies of the presentation and report were provided to the VEGA center to ensure its ability to employ the results for decision-making. Should VEGA decide to proceed with the change, its sustainability will be promoted by the nurses’ enthusiasm and the positive outcomes of the pilot change, including the quality of care wins and the successful adoption of the guidelines.

The results will also be disseminated at my educational institution as my DNP project. However, no publications or conferences are planned. While some options have been considered for a while, the results of the project are predominantly of interest to its settings. As a result, it appears reasonable to focus on the stakeholders and use the results to demonstrate my skills as a DNP-prepared nurse.

Summary and Conclusion

The present paper has provided an overview of the project dedicated to the introduction of NICE (2016a) guidelines within the settings of the VEGA Medical Center. Being guided by the Iowa Model of Evidence‐Based Practice, the project started with a needs assessment that demonstrated the absence of depression management guidelines at VEGA. The project then proceeded to review the key literature on the topic to reveal the appropriate guidelines and prove their appropriateness (the fact that they are based on evidence). The project took the form of a pre-test post-test study with the sample of ten nurses and involved the introduction of the guidelines, training, and summative and formative assessments. The former was carried out with the help of NICE (2017) quality standards, and the latter involved group discussions that took the form of interviews. Kotter’s (2012) model and Rogers’ (2010) theory were employed to manage the change.

The major findings of the study indicate that the NICE (2016a) guidelines have managed to improve the quality of care in VEGA nurses with respect to three quality indicators. The performance of the nurses in relation to the majority of the indicators was high before the beginning of the project, but by its end, 100% compliance with the standards was achieved (with the exception of the cases of justified non-compliance). Apart from that, the nurses reported their approval of the guidelines and the willingness to use them. Thus, it may be concluded that the project was successful, and it can be recommended to proceed with the change. Also, the project established that the key issues experienced by the nurses during the change involved the adjustment period and the need for training. The factors that could assist the nurses with the two challenges were viewed as facilitators. The information about change management can be of interest to professionals outside of the settings. The results of the project were presented to VEGA stakeholders for future decision-making.

References