The practice of allowing family members in the resuscitation rooms is one of the controversial issues in the field of medicine. According to McLean, Gill, and Shields (2016), the current standard procedure is to ensure that friends and family members are kept away from the resuscitation rooms to ensure that the medical staff has ample time to overcome the condition. Scholars who support the idea of keeping family members away from such emergency procedures argue that they are less likely to play a significant role in helping the patient.

In fact, their presence may interfere with the whole process than provide any meaningful help. However, some scholars have argued that it is advisable to allow family members into such emergency rooms. It helps them cope with the painful condition in case the patient does not make it through the process. It creates a sense of teamwork between the medical staff and members of the family as they struggle to address the condition of the patient. In this paper, the focus is to find a way of addressing this controversial issue.

Evidence-Based Solution

Medical researchers have conducted various studies to help explain the relevance of allowing family members into the resuscitation rooms as a way of enhancing the outcome (Reeves et al., 2015). In many cases, these family members often demand to be allowed to be part of the resuscitation process, even if they do not play active roles. However, they are often denied access because of the standard practices that require the medical staff to have time to conduct the procedure without any interference.

Dwyer and Friel (2016) argue that there is always a fear that allowing family members into emergency rooms may be a recipe for chaos. They may try to be directly involved in the process, causing direct interference to the medical staff. Others may be aggressive and even abusive to the staff involved in helping their loved ones. There is also a fear that if the patient is lost, the loved ones may become physically abusive to the staff involved in the resuscitation process. Crowding the resuscitation rooms may also be less advisable, as Stanley (2017) notes. These factors led to the current practice where family members are not allowed into the emergency rooms.

New studies suggest that it may be essential to include a few family members in resuscitation rooms. Reeves et al. (2015) focused on several studies using PubMed, Proquest, and Ebsco, and found out that it may be necessary to involve family members in such processes for their own benefit and for that of the medical staff. Their findings were supported by Stanley (2017), who reviewed more than 30 studies in CINAHL, Medline, and Meditext. The studies suggest that allowing family members into resuscitation rooms makes them understand what doctors are doing to help their loved ones.

In case the patient fails to make it, the family will understand that the medical staff did everything within their powers to save the patient. They will be in a better position to cope with post-traumatic stress disorder associated with the loss of a loved one. The medical staff will be vindicated in such processes. There will be proof that they did everything within their powers to save the patient. Dwyer and Friel (2016) also argue that such practices also enhance a sense of responsibility among medical staff. Sometimes patients are lost because of mistakes committed by doctors or nurses in such a process. The knowledge that their activities are watched would make them more responsible.

When defining the inclusion criteria, it is important to take into consideration the interest of the medical staff. As Reeves et al. (2015) observe, family members should not be part of the team involved in the resuscitation process. Instead, they should be allowed into a particular room with a screen or a glass wall separating them from the medical team involved in the resuscitation process.

Figure 1 below shows how these family members should be engaged in such a process. The idea in the inclusion criteria is to address the controversy by taking care of the interest of both the medical staff and family members. In these special rooms adjacent to the emergency rooms, family members will be allowed to observe the entire process without interfering with the activities of the medical team.

Change Theory

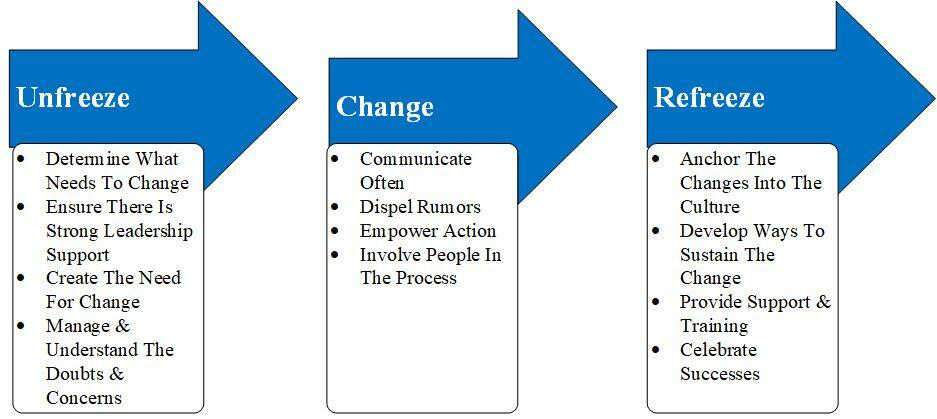

Introducing change in an organization can be a challenging process. According to Bradley, Keithline, Petrocelli, Scanlon, and Parkosewich (2017), sometimes stakeholders may reject a new concept because of the fear of the unknown. As such, it is advisable to embrace theories of change that may make the process seamless. In this context, the most appropriate theory would be Kurt Lewin’s model of change. It proposes a systematic process of introducing change in an organization through three different stages. The first stage, known as unfreeze, involves preparing the team for what is to come.

The medical staff will have to be prepared to handle a situation where family members of the patient would monitor their activities during the resuscitation process. They should be informed about the benefit of the new process. In case they have any reservations, such issues should be addressed to ensure that they are comfortable. The second stage, known as the change process, involves the actual introduction of the new concept or practice (Dwyer & Friel, 2016). The team will start including family members in such processes to determine if it will have the desired impact. If it works, the final stage is to refreeze, where the practice is internalized into the organizational culture of the institution. Figure 2 below summarizes these stages.

Project Plan

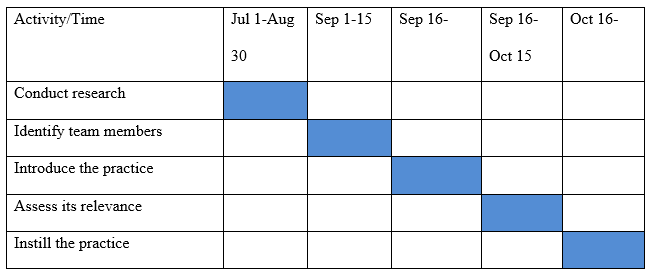

The plan is to introduce the new practice in the selected hospital to determine if it will have the desired impact on nursing practices during the resuscitation process. The first step is to conduct research on the topic to determine what scholars believe is the best way of implementing the project. The team will then identify the most appropriate process. The next step is to identify a team of medical experts who will be involved in the initial implementation of the plan.

When team members have been identified and adequately prepared, the new practice will be introduced. An assessment team will also start investigating the pros and cons of the new procedure with the view of establishing its relevance in the institution. If it is determined to be beneficial, the final stage will be to instill the new practice in the institution. Table 1 below shows the proposed timeline for these activities.

Use of New Modalities in the Plan and Integration of Program Courses

When introducing the new practice, it is important to prepare the medical team effectively to ensure that they are prepared to handle different situations. The use of new modalities in the plan would be advisable to ensure that the desired outcomes are achieved (Twibell, Siela, Neal, Riwitis, & Beane, 2018). One of the modalities is the use of simulations. Such innovative training processes would enable the medical team to experience what they will face in the emergency rooms.

The simulation creates an experience that would equip the team with unique skills needed to handle different challenges that may arise. They can plan on how to enhance patients’ safety, their own security, and the success of the entire process. Program courses such as managing change resistance in a medical setting would be crucial in planning the implementation process.

Conclusion

The current standard practice prohibits family members from accessing resuscitation rooms as a way of creating a perfect environment for the medical team to attend to a patient. However, some studies have suggested that it may be appropriate to allow friends and family members into the emergency room to witness the resuscitation process. It may not only help the loved ones to cope with a possible loss but also make the medical team more responsible because they are aware their actions are under surveillance. The researcher believes that when introducing this new practice, measures should be taken to protect the medical team and to ensure that they can work without interference.

References

Bradley, C., Keithline, M., Petrocelli, M., Scanlon, M., & Parkosewich, J. (2017). Perceptions of adult hospitalized patients on family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. American Journal of Critical Care, 26(2), 103-110.

Dwyer, T., & Friel, D. (2016). Inviting family to be present during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Impact of education. Nurse education in practice, 16(1), 274-279.

McLean, J., Gill, F. J., & Shields, L. (2016). Family presence during resuscitation in a paediatric hospital: Health professionals’ confidence and perceptions. Journal of clinical nursing, 25(7-8), 1045-1052.

Reeves, S., McMillan, S. E., Kachan, N., Paradis, E., Leslie, M., & Kitto, S. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration and family member involvement in intensive care units: emerging themes from a multi-sited ethnography. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(3), 230-237.

Stanley, D. (Ed.). (2017). Clinical leadership in nursing and healthcare: Values into action. Chichester, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

Twibell, R. S., Siela, D., Neal, A., Riwitis, C., & Beane, H. (2018). Family Presence During Resuscitation: Physicians’ Perceptions of Risk, Benefit, and Self-Confidence. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 37(3), 167-179.