Abstract

The article presents the concepts of Middle Range Theory (MRT) in a scholarly approach. As a student of the Nursing Practice program, the work incorporates evaluating nursing practice applications. The research, incorporating primary and secondary sources, expanded the ideas of nursing practice by adopting the Wounded Healer theory. The connection between the selected MRT and nursing practice occurred through the division of the text into numerous headings.

Philosophical understandings and the main issues of MRT facilitated the attainment of a suitable QUEST model. According to the analysis, the wounded healer and Jung’s philosophical concepts contribute to the alteration of nursing practices. The relationships between nurses and patients increase with earlier exposure to traumatic events. Moreover, the research echoed nurses’ concerns about their own suffering in cases where they felt their efficacy in handling wounded individuals was lacking. Online research on middle-range nursing theory highlights the significance of the concept in explaining complex nursing practices and alternatives to workplace stress.

Introduction

The nursing profession is guided by principles, policies, and beliefs that distinguish the field from other medical occupations. The Middle Range Theory (MRT) is crucial in describing various aspects limited to the scope of nursing application. According to Brandão et al. (2019), nurses encounter complex workplace conditions that expose the experts to the dilemma of handling patients.

Middle-range theories are essential in nursing and healthcare because they provide a comprehensive explanation of how to address many challenging circumstances in nursing practice. These theories are considerably simpler than the grand nursing theory. The MRT focuses on nurses’ experience in practice and how they deal with traumatic situations (Fawcett, 2021). It is easier to comprehend how the theory is used in healthcare settings and the benefits it offers nurses if individuals are aware of its essential components and structure.

Philosophical Underpinnings

The image of the injured healer has been employed since the existence of the Greek mythology archetype, which suggests that healing power originates from injury. According to Greek tradition, the wounded healer archetype originates from an existing injury. The character traits of Chiron, a gentle centaur, expand students’ knowledge of the MRT approach. Chiron fled to his cave after receiving an irreversible wound from Heracles’ arrow.

Hadjichristodoulou et al. (2019) stated that Chiron’s immortality prevented him from being poisoned by the arrow. Similarly, nurses assume their role of monitoring patients even in their lowest state to protect their clients from psychological and physical damage. Evaluating Chiron’s selfless gesture in Greek traditions highlights the role of nurses in mitigating, transcending, and alleviating patients’ challenges.

Psychology, psychotherapy, and religion often employ the concept of the wounded healer in various situations. The MRT is used to characterize doctor-patient interactions, with the practitioner employing themselves to help the patient recover health. Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist and founder of analytical psychology, expanded the concept of the wounded healer. Jung assumed that everyone had undergone trauma in his research on the relations between MRT and the nursing practice.

In Younas and Quennell’s (2019) article, personal experiences influence conscious and unconscious human behavior. Instead of dichotomous, these elements coexist; seeing “duality” as a totality is termed “transcendence,” in Fawcett’s (2020) opinion. MRT concepts extend self-evaluation beyond regular experiences in nursing practice. To reach ‘wholeness’ in defining nursing practice, Jung’s approach to nursing theory sought interactions, links, and combinations within the globe around him, in line with humanity’s quest for transcendence.

It has been said that to do their jobs effectively, medical professionals must be entirely emotionally well. On the other hand, Jung maintains that nurses and healthcare practitioners are human, just like everyone else, and that it’s more vital to seek completeness than ‘clean-hands perfection’ when it comes to healthcare. Frisch & Rabinowitsch’s (2019) “countertransference” theory describes the subconscious and conscious processes at play when a wounded healer interacts with a patient. Jung believed that a sufficiently healed injured healer might employ countertransference to promote empathy and facilitate the healing process.

The philosophical ideologies supporting the implementation of middle-range nursing theory draw on the frameworks of the wounded healer, relating nursing problems and recent solutions to each challenge. Research conducted by Lopes & Nihei (2020) illustrated that patients may suffer from the underlying discomfort caused by poor healing processes initiated by incorrect nursing practices. Marion Conti O’Hare, a nurse in the detoxification unit at Southside Hospital, explained the concept of MRT through the wound healer approach. According to the nursing spectrum ambassador, nurses need healing from the problems they experience in practice.

O’Hare established the nurse as wounded healer idea as a paradigm that associates patients and the affected medical team. Kruglanski et al. (2022) suggested that O’Hare’s views on the wounded healer align with Jung’s beliefs in nursing; the only way for nurses to heal from their suffering and move beyond it is to face it directly. In this way, the nurse’s distress and discomfort are an inevitable component of the maturation process for the professional. The use of the self in therapy is proportional to the degree of trauma resolution; only then can personal healing experiences aid others. Emotional discomfort and self-destructive behavior might occur if a nurse does not distinguish between pain and fear.

Conti O’Hare addressed essential assumptions while developing the concept of the nurse as a wounded healer. All humans encounter violence or trauma in their personal or professional lives. Pain and terror from the encounter often last a lifetime; they do not resolve themselves. According to Foli (2021), trauma affects one’s capacity to care for others; however, the mental status may be transformed in the nursing practice to assist patients in overcoming their emotional disturbances.

Transitioning from traumatic experiences to a more positive view of life-challenging situations empowers nurses to maximize their understanding of self-therapy. The concept of healing entails an individual’s ability to accept their current position and hold a belief in a better future. The wounded healer’s philosophical understanding depends on the nursing practice policy; the afflicted must first heal themselves to achieve the implementation of MRT.

Main Concepts of the Theory

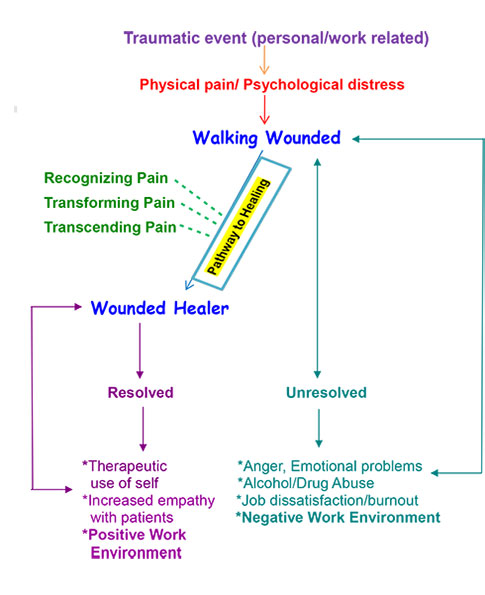

The medical practitioner, specifically the nurse, is crucial to the concepts of healing, health, and environment in patient care, which are the four main concepts typically connected to O’Hare’s theory. These four concepts manifest in different stages for the nurses.

The quest for wholeness is a fundamental concept integrated into O’Hare’s framework of nursing practice. The aspects of becoming an all-around nurse begin with acknowledging nursing problems. Hadjichristodoulou et al. (2019) suggest that the concept of the wounded healer embodies the wholeness of healthcare professionals, who become both patients and nurses.

Secondly, the transformation of nurses can occur through personal growth or trauma; the assumption that terrific events impact the productivity of nurses is a key priority in O’Hare’s framework. The therapeutic ability of nurses to help wounded individuals formulates the primary assumption of the theory. Nurses’ counseling services expand the healthcare specialists’ ability to handle trauma-related psychological issues.

- Recognition. The realization, via internal reflection and assessment or external validation from other people, that one is experiencing a negative effect in their life from something.

- Transformation. Employing stored-up vitality to enhance present-moment perception; exploring therapeutic and social contexts to gain acceptance of and mastery over painful feelings like grief and fear.

- Transcendence. A more profound comprehension, whether through higher thinking or spirituality, may be utilized in an individual’s healing interactions with others.

- Walking Wounded. Those who have been through emotional or physical trauma but have not dealt with it often find that they cannot cope with everyday stresses, which may have negative consequences.

- Wounded Healer. Those who acquire expanded awareness through self-reflection and spiritual development can process, transform, and heal trauma. The scar remains, allowing the individual to appreciate the anguish of others more deeply.

Traumatic exposures are inevitable in the medical care environment. Nurses and other medical care workers are referred to as “walking wounded” because of the traumatic environment in which they work while undertaking their duties. Dubé et al. (2021) emphasized the importance of nurses in simultaneously attending to patients with diverse needs to explore the MRT approaches. In the analysis, nurses appear to be strong professionals who recover from traumatic experiences caused by exposure or personal stress more swiftly than patients. The capacity of nurses to participate in the recovery of patients, despite their challenges, aided the development of the notion of the “wounded healer.”

The everyday experiences of healthcare workers are the starting point for this idea. A “Wounded Healer” is a medical professional who has experienced trauma but can now recuperate and return to provide vital care to hospital patients. To recover from the severe stress they experienced on the job, nurses turn to various methods of self-care and support. One option is to learn to cope and use their experience to help others by becoming a “wounded healer” and providing services based on their unique circumstances. On the other hand, they could not get well and continue to be a burden on healthcare systems.

It is possible that providing care for traumatized people may put a strain on an individual’s emotional and mental health. The latest epidemic’s high death toll and widespread suffering made hospital work more challenging. A great deal of emotional strain is placed on nurses who work in intensive care units and emergency rooms. As a result, Leandro et al. (2020) echoed that more resources are required to sensitize and prioritize trauma concerns among nurses. These traumatic encounters have long-term consequences for their careers and personal lives.

However, the caregiver may transform into a wounded healer if the trauma is addressed and the suffering is acknowledged. Pain is recognized as a regular part of maturation; alternatively, Owusu-Addo et al. (2020) define pain based on the interference of routine care offered to patients in the challenging workplace. O’Hare’s theory delves into how nurses might get beyond their own experiences of trauma to create more productive therapeutic relationships with patients.

As a result, “therapeutic use of self is reliant on the degree to which the trauma is transcended; only after this transcendence may personal healing experience be utilized to benefit others.” In addition, Lopes and Nihei (2020) identified improvised technological experience, listening skills, optimistic reasoning, transit healing, and empathic understanding as the primary characteristics of effective nurses.

The Model of the Theory

The QUEST Model

Incorporating the QUEST Model for consciousness into the theory, O’Hare aims to support nurses and other healthcare professionals in evaluating their capacity to manage trauma and recover. The plan includes five stages of introspection to aid recovery. The model suggests that one must reflect on their experience of assisting others to fully appreciate the significance of knowledge about helping others (Kruglanski et al., 2022).

Injured healers can transform a negative experience into a positive one by remaining optimistic, recognizing the potential benefits of the injury, asking pertinent questions, and, ultimately, consciously applying what they have learned. The QUEST promotes personal and professional well-being among nurses and other healthcare providers. It also operates with many assumptions, the dominant one being the ending characteristics of change and development.

The ability to help others in nursing depends on the trauma patterns identified in specific individuals. The continuous suffrage of individuals is present in all relationships; similarly, Leandro et al. (2020) argue that nurses gain experience through interactions with more complex workplaces. Therefore, the more a person interacts with numerous terrifying events, the higher the chances of such a person having solutions to the main problems associated with trauma.

Thirdly, the QUEST model assumes that the first step toward healing involves the likelihood of accepting the predominance of trauma in workplaces. Nurses can operate with fewer struggles in the complex surroundings if they accept the existence of trauma in the profession (Foli, 2021). Another trending myth about the model incorporates insights from personal growth; the agony of trauma allows nurses to find liberation at work.

The QUEST paradigm has five steps: question, uncover, experience, seek meaning, transform, and transcend. Inquiry, the first stage, involves reflective thinking about how the trauma has changed their life. The second phase is to identify the trauma pattern, which typically contains details that are difficult to recall and may entail the possible repercussions of reliving traumatic memories. The next phase is similarly challenging since the injured may be unable to acknowledge the trauma and may block specific incidents.

The experience stage requires one to reflect on their thoughts about the incident and gain a fresh perspective. The search for meaning is often considered essential in the QUEST procedure. “Searching for and comprehending the meaning of pain becomes a vital goal to achieve a higher degree of awareness and transcendence” (Kruglanski et al., 2022). The last phase is transformation and transcendence. The injured begin to view their previous painful experiences with fresh eyes and learn to forgive themselves and others.

Jung’s Model

People from various countries and civilizations employ the wounded healer archetype. The Greek tale of Chiron, mortally wounded by Heracles’ arrow, is where the wounded healer first emerges in Western philosophy. When Chiron survived this wound, he went on to treat others, demonstrating that wounded healers may connect the realms of disease and health.

A healer’s capacity to help others helps them overcome or transcend their wounds. In Jung’s (1961) perspective, the concept of the wounded healer offers valuable insights for clinicians. Others may worry that wounded healers will bring the SWHS field into disrepute. The following are essential things to think about while adopting Jung’s archetype.

First, there’s the potential for countertransference, which may manifest in various ways. Wounded healer trainees show increased resilience. Furthermore, the possibility of burnout and vicarious trauma. By carefully analyzing these three areas, we may gain insight into the dangers and rewards that wounded healer students may bring to the healthcare field. Given the prevalence of childhood trauma and its potential effect on medical practice, a nuanced and scientifically based understanding of wounded healer students is crucial for meeting their learning needs.

The wounded healer defines traumatized individuals as people with terrible psychological suffering or worry. Nurses naturally incorporate their life experiences into their work; thus, the population is exposed to trauma-related events (Macfarlane, 2020). In Jung’s archetype, a caring professional does not become a wounded healer just by going through a traumatic event (Macfarlane, 2020). In Jung’s view, trauma and hardship can only be enlightening to the extent that the practitioner undergoes a transition due to the experience.

Personal therapy is a common approach in Jung’s area of psychotherapy to achieve this end. Individual self-reflection, workplace monitoring, or external monitoring are viable options in today’s social and health services practice environment. This change process may occur for aspiring social and health services practitioners in academic settings. In light of this, it is clear that colleges play an essential role in helping Jung’s students overcome the challenges of their upbringing.

According to critics, “Woundedness does not consider a person’s unique set of experiences. If you don’t accept your ‘wounded’ personality, it might seem like a deficiency rather than a source of strength.” Criticism of health workers, which focuses on the circumstances in which they help others rather than on an individual’s shortcomings, is particularly relevant here. A strengths-based approach enables the creation of resilient and empowered practitioners by analyzing and incorporating prior unpleasant experiences. A study of the incidence of adverse childhood experiences is conducted to determine the degree to which wounded healers pursue education in social and health services.

Heuristic Value of the Theory

Nursing may be highly demanding; as a result, specific theories are incorporated into the occupation to offer professional guidelines and monitoring skills. The MRT, for instance, has been effectively utilized in healthcare settings to assist nurses in providing treatment based on past experiences handling relevant difficulties and personal trauma. Furthermore, the notion might be used in nursing programs to help students learn to cope with and even benefit from trauma.

What occurred, according to this theory? What effect has the action had on the people around me or me? And how can I improve things? Answering such questions is a critical step in becoming a wounded healer. This theory has the potential to improve nursing procedures and enhance the quality of care provided to patients.

The philosophy encourages feelings of caring towards those less fortunate. Nurses can channel their healing energy and deliver superior patient care through improved therapeutic contact (Younas & Quennell, 2019). However, there are constraints to this theory. As a preliminary matter, it is restricted to medical professionals. It is cumbersome to use, as it is tailored specifically for nurses. Yet, a healthcare setting often involves a wide range of specialists, from physicians to social workers. There is also no assurance that the terrible events will not bring up painful memories for the nurses.

It is essential for there to be positive interactions between the people providing medical care and the people receiving it. The metaphor of the nurse as a wounded healer inspires doctors and nurses to reflect on their experiences for lessons they can apply to their patients’ treatment. The hypothesis has been successfully applied in clinical practice, according to a recent study.

McAllister (2017) highlighted the heuristic values for MRT in increasing the emotional weight of the professionals. In the survey, 45% of nurses tasked with child care experienced major depressive disorders from workspace conditions. However, adopting MRT in such environments improved the emotional well-being of nurses; although a few individuals experienced psychological health issues, most of the population was mentally stable (McAllister, 2017). The heuristic advantages of MRT enabled the nurses to become wounded healers; the medical professionals assisted patients in overcoming post-traumatic stress disorders that had been previously diagnosed.

Analysis

Theorist Motivation

A person interested in assisting others on their road to recovery may choose to pursue a career in nursing as a helping profession. In this line of work, individuals handle the needs of clients who are in a fragile state. According to O’Hare, the desire to help others cope with their suffering first attracts many individuals to assisting professions, such as nursing, after they have experienced or witnessed tragedy themselves. The death of a family member is only one example of such a situation.

Assumptions

O’Hare’s theory of the wounded healer has several assumptions that must be considered for its implementation in nursing. First, the theory assumes that every human being is exposed to violent experiences leading to trauma. As a result, the theory suggests that nurses become better healers for their clients after undergoing traumatizing events. Secondly, nurses experience personal and public trauma based on their workplace environment. Lopes and Nihei (2020) critique the ideology because not everyone is entitled to trauma experience; experience, talent, motivation, and passion can motivate nurses to work better.

A third myth about the wounded healer theory stresses the similarities between terror and trauma-induced pain. In Macfarlane’s (2020) argument, trauma exposes individuals to emotional problems that affect the output of work delivered in any environment. Therefore, past traumatic events in a nurse’s life can have a lasting impact throughout their life, based on the aspects of the theory’s assumptions. Trauma needs psychological treatments; the traumatic experiences faced in life do not disappear naturally; instead, the adoption of psychotherapies speeds the recovery of affected people.

Theory Classification

The theory by O’Hare is categorized as a middle-range theory. Its more significant specificity characterizes the MRT since it investigates just one specific instance and a constrained set of potential variables. As middle-range theories are tested in the real world, the grand nursing ideas to which they may be related become helpful as reference points for further developing those theories. Additionally, direct the prescriptions of practice theories toward achieving actual goals.

The following paragraph indicates the structure of the nurse as a wounded healer theory. In this idea, there are only two possible responses to trauma. A person may learn to deal with harsh experiences and emerge unscathed. On the other hand, individuals may not be able to heal their emotional scars and hurt because they cannot cope adequately with their traumatic experiences. Consequently, they may have to deal with the aftereffects of the trauma. Another facet of this concept is that if one person can successfully recover from a traumatic event, they will be better able to help others do the same.

Critique

Nurses can use this idea to better understand their patients’ concerns and provide effective support during therapy. Nurses’ reliance on unrelated experiences when caring for patients remains a topic of debate. A moment may come in the future when people cannot always depend on their past experiences to help their clients. Institutions may help nurses recover from traumatic experiences by providing access to therapy and support services and advocating for broader use of this paradigm in nursing.

Theory Application to Lateral Violence in Nursing

Some studies have even shown that nurses experience greater levels of anxiety and burnout than active-duty military personnel. Nurses may feel overwhelmed when their professional and personal lives collide. Nurses, like everyone else, need an “outlet” to express their unpleasant feelings and thoughts.

Unfortunately, vulnerable friends and coworkers are often used as this outlet, making them victims of lateral aggression (Faremi et al., 2019). These attacks are usually directed towards recent graduates who need mentoring, inexperienced caregivers who are uncomfortable with the ward or their assignments, and night-shift nurses who are stereotyped as less dedicated to their profession. Sadly, these victims turn into the walking wounded, which keeps the cycle of lateral violence (LV).

Whether work-related or personal pressures create the wound, single occurrences of LV may begin with passive aggressiveness or mild bullying aimed toward people who are viewed as lower or weaker. An apology may help in the short term. Still, the problem will likely resurface, and it might even escalate into verbal abuse or other harmful actions that could devastate morale and safety in the workplace.

As the violations continue, this behavior may become the norm. With so many patients suffering from LV and the nursing staff being drained by the effects of LV, the ward may soon be overrun by the injured (Bambi et al., 2019). According to the wounded healer theory, every nurse must recognize and transform their own anxiety and sadness to overcome them and embark on the path to becoming a wounded healer. These three phases are outlined below: recognition, change, and transcendence.

The ability to ‘recognize’ the trauma and its repercussions enables a careful inspection and deconstruction of the components. Familiarizing oneself with trauma or its impacts on individuals begins with analyzing particular nursing practices. Nurses often ask themselves about the possibilities of adapting an emergency approach when handling clients to increase the chances of an effective response to such challenges.

The nurse can move on to “transformation” once they have established recognition. Through these inquiries, the nurse may help the patient understand the nature of their pain and develop strategies for coping with it. McAllister (2017) holds that the transformation stage enables nurses to identify ordeals and dilemmas in a pre-existing situation. Professionals may pre-empt incidents that affect wounded persons or nurses at large by understanding the transformation of lateral violations in practice. Frisch & Rabinowitsch (2019) suggested that the transformation phase in nursing practice enables the medical specialists to improve the observable obstacles in formulating conducive workplace environments.

The last step, transcendence, happens only once the previous two phases have been fully accomplished. Transcending the anguish offers insights and lessons from earlier experiences that can be applied to benefit individuals who are experiencing pain and suffering. The professional exhibits transcendent behaviors when a nurse makes specific statements, such as feeling the anguish of an event or associating with a patient. For instance, if a nurse asks patients about their needs, they must have observed an existing or past trait that needs attention.

Following these three steps, the walking wounded becomes the wounded healer, able to better understand and empathize with the plight of others. When people in the same profession work together effectively, it makes the workplace more pleasant and improves the quality of patient care. However, let us assume that nurses are again put in a position where they must deal with traumatic experiences or LV. To regain their position as wounded healers, nurses must undergo the process of self-awareness, transformation, and transcendence once again.

Conclusion

Researchers developed the theory of the nurse as a wounded healer to understand how nurses are affected by witnessing or experiencing lateral violence. As with any other kind of trauma, the route to recovery from LV may be as harrowing and life-altering as any other. The nurse’s road to becoming a wounded healer is well-suited to the journey of the walking wounded, who undergo identification, transformation, and transcendence.

To detect the impacts of trauma and the need for treatment, practitioners and managers must be aware of its existence. When patients’ lives are in danger, all options for resolving the traumas must be considered. Nurses must work to improve their well-being as well as the well-being of admitted patients.

References

Bambi, S., Guazzini, A., Piredda, M., Lucchini, A., De Marinis, M. G., & Rasero, L. (2019). Negative interactions among nurses: An explorative study on lateral violence and bullying in nursing work settings. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(4), 749–757.

Brandão, M. A. G., Mercês, C. A. M. F., Lopes, R. O. P., Martins, J. S. de A., Souza, P. A. de, & Primo, C. C. (2019). Concept analysis strategies for the development of middle-range nursing theories. Texto & Contexto – Enfermagem, 28(4), 104–137.

Dubé, M., Laberge, J., Sigalet, E., Shultz, J., Vis, C., Ball, C. G., & Biesbroek, S. (2021). Evaluations for new healthcare environment commissioning and operational decision-making using simulation and human factors: A case study of an interventional trauma operating room. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 14(4), 442–456.

Faremi, F. A., Olatubi, M. I., Adeniyi, K. G., & Salau, O. R. (2019). Assessment of occupational-related stress among nurses in two selected hospitals in a city in southwestern Nigeria. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 10(3), 68–73.

Fawcett, J. (2021). Thoughts about models of nursing practice delivery. Nursing Science Quarterly, 34(3), 328–330.

Foli, K. J. (2021). A middle-range theory of nurses’ psychological trauma. Advances in Nursing Science, 45(1), 86–98.

Frisch, N. C., & Rabinowitsch, D. (2019). What’s in a Definition? Holistic Nursing, Integrative Health Care, and integrative Nursing: Report of an Integrated Literature Review. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 37(3), 260–272.

Hadjichristodoulou, C., Dresios, C., Rachiotis, G., Symvoulakis, E., Rousou, X., Papagiannis, D., & Mouchtouri, V. (2019). Nationwide epidemiological study of Greek general practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to screening. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(1), 199.

Kruglanski, A. W., Molinario, E., Jasko, K., Webber, D., Leander, N. P., & Pierro, A. (2022). Significance-Quest theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(4), 1050–1071.

Leandro, T. A., Nunes, M. M., Teixeira, I. X., Lopes, M. V. de O., Araújo, T. L. de, Lima, F. E. T., & Silva, V. M. da. (2020). Development of middle-range theories in nursing. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 73(1).

Lopes, A. R., & Nihei, O. K. (2020). Burnout among nursing students: Predictors and association with empathy and self-efficacy. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 73(1).

Macfarlane, S. (2020). The radical potential of Carl Jung’s wounded healer for social work education. The Routledge Handbook of Critical Pedagogies for Social Work, 4(1), 322-332.

McAllister, M. (2017). Nurse as a wounded healer in The English Patient. TEXT, 21(Special 38), 113–127.

Owusu-Addo, E., Renzaho, A. M. N., & Smith, B. J. (2020). Developing a middle-range theory to explain how cash transfers work to tackle the social determinants of health: A realist case study. World Development, 130(18), 104–920.

Younas, A., & Quennell, S. (2019). The usefulness of nursing theory‐guided practice: An integrative review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(3), 540–555.