Introduction

Background

Nurses are an integral component of the health care system. Patients receive high-quality and safe treatment as a result of the stability of this pillar, which contributes to efficient healthcare care delivery (Halcomb et al., 2018). In a setting where nurses are under great pressure, they provide basic and difficult care to their patients. They do a large number of non-nursing duties while neglecting to complete numerous critical nursing responsibilities. Among professional nurses, the most common source of work discontent is the failure to complete nursing tasks on time (Bekker et al., 2015).

Non-nursing tasks are responsibilities performed by a professional nurse that are not within the scope of practice of nursing as defined by the nursing profession. Non-nursing tasks, which are defined as duties that do not necessitate professional nursing training and that must be delegated to other staff unless in unusual circumstances, include serving and collecting meals, cleaning, moving patients, issuing orders, receiving instruments, and organizing discharge referrals (Ahmed et al., 2020).

Leaving nursing tasks undone is a serious issue in hospitals, with 55–98% of nurses indicating that one or more essential care activities were left undone at the time of evaluation [which was typically the previous shift completed] (Hammad et al., 2021). The ambulation and turning of patients, oral care, feeding patients on time (including comfort talks with the patient and his family), patient education, medication administration on time (including documentation), and ambulating and turning of patients were the items missed most frequently (Palese et al., 2015).

However, nursing care that is left undone or carried over to the following work shift is a mutually beneficial practice. Furthermore, the reasons for missing care are complex and varied (Marven, 2016). In particular, organizational problems, such as personnel shortages, inefficient or absent cooperation, and a lack of a positive workplace safety environment, could contribute to an increase in the number of nursing activities that go unfinished (Ahmed et al., 2020). In Saudi Arabia, a shortage of nurses has caused an increase in the recruitment of foreign nurses, resulting in a significant increase in workload (Alsadaan et al., 2021).

Job satisfaction is one of the subjects most studied to evaluate the behaviors and attitudes of nurses toward the institution (Roney & Acri, 2018). It is significant to assess the level of job satisfaction to provide professionalization in nursing and improve the quality of care (Kantek & Kaya, 2017). Several studies have investigated the association between nurse job satisfaction and nursing tasks left undone. But no studies have revealed this problem in Saudi Arabia.

The resolution of the issue of non- nursing tasks is an international phenomenon. Nurses were spending significant amounts of time in doing the non-nursing tasks, which in turn affect their job satisfaction and lead to missed nursing care and left nursing tasks undone. This will negatively affect the quality of care provided to patients and will have an adverse effect on the general health of patients.

International studies have shown a considerable influence on work satisfaction that non-nursing tasks and nursing tasks that are left undone, respectively, have on a person’s ability to care for others (Bekker et al., 2015). According to the findings of Bekker et al. (2015), nursing duties left undone were only associated with three non-nursing activities, and work satisfaction was shown to be most strongly associated with nursing tasks left undelivered. Studies on this issue are considered lacking in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing tasks left undone among Saudi nurses at government and private hospitals.

Significance of the study

The results of this study will help nursing managers, hospital managers, policy makers identify which factors help to reach the required level of nurse satisfaction and will have effective future recommendations for policy makers and nurse managers, which in turn will increase work productivity and performance among nurses by hiring other nurse aids to perform non-nursing tasks, which in turn will affect patient health in positive way.

This study will contribute to the achievement of the “Gold Standard” in nursing practice as promised by the Saudi government in the 2030 Saudi Vision regarding the improvement of nursing working environment to retain and empower nurses and will contribute to the growth of nursing as a profession and strengthen the backbone of the healthcare system transformation in KSA.

Aim of the study

The current study sought to determine how Saudi nurses working in government and commercial hospitals in AL Madina AL Munawara related to their job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing activities left undone.

Research Questions

- What is the level of job satisfaction among nurses?

- What is the frequency of non-nursing tasks performed by nurses?

- What is the frequency of nursing tasks left undone among nurses?

- Is there a relationship between job satisfaction, non–nursing tasks, and nursing tasks left undone among nurses?

Definition of research key terms

Nursing tasks left undone

Refers to the failure to provide, or delay in providing, any component of treatment that the patient needs in part or in whole (Lima et al., 2020).

Non-nursing tasks

Non-nursing tasks are defined as those that do not require professional nursing training and that must be delegated to other staff unless there are exceptional circumstances, such as serving and collecting meals, cleaning, moving patients, issuing orders, receiving instruments, and organizing discharge referrals (Hopkins et al., 2012).

Job satisfaction

A level of job satisfaction can be described as the degree to which you feel positive or negative about the work you do. It is a response to work and the environment of the workplace that encompasses several dimensions and increases positive energy and performance (Singh et al., 2019).

Literature Review

Overview

This chapter introduced the reader to the literature review and previous studies on missed nursing care and nursing tasks left undone, as well as the association between job satisfaction with nursing care left undone.

Data extraction

Data extraction was carried out by researchers independently. The data extracted in addition to other studies provide important and effective results.

Search strategy

Different databases were used for the search strategy, and for systematic literature search, databases include: Saudi Digital Library and EBSCO. These search key terms were used as: nurses, nursing tasks, nursing duties, nursing tasks left undone, nursing duties left undone, ” missed nursing care “, non-nursing task, satisfaction, job satisfaction, Relationship between and nursing tasks left undone (Appendix 1).

Included and Excluded Studies

Studies that have been published in English, published in peer-reviewed journals and that matched the study topic; have been included in the current study. However, studies published before 2012 (except for tools), and studies applied to healthcare providers other than nurses; have been excluded.

Literature search results

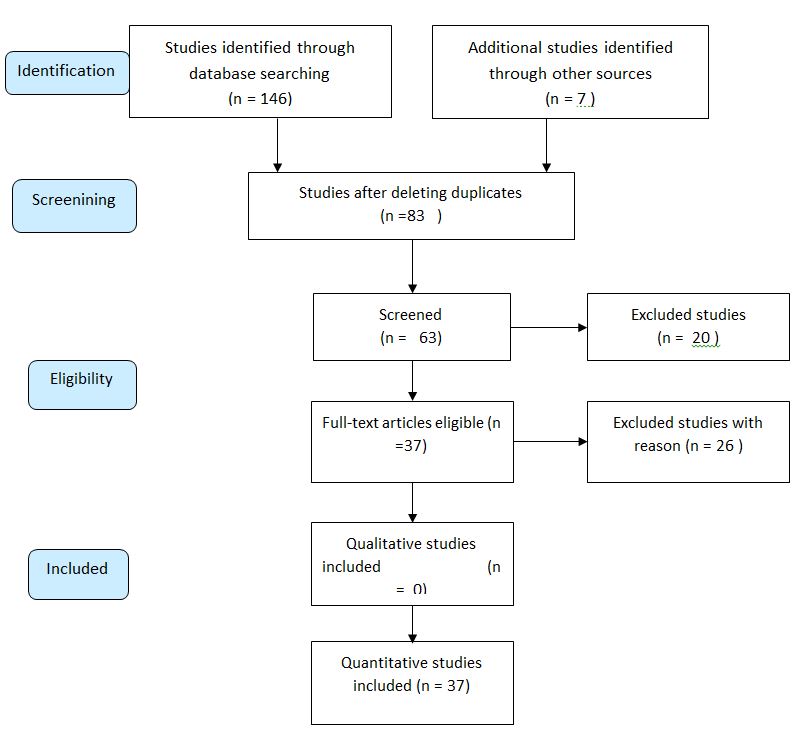

Based on the keywords that have been used in the search process, the results were identified and illustrated in this chapter (Figure 1).

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Synthesis of evidence

Several national and international research studies related to nursing tasks left undone and non-nursing tasks as well as nurses’ satisfaction. These studies have been reviewed very well through investigating its objectives, methods, data analysis and results, and conclusion. In this paper, 153 articles were searched. After conducting a duplicate check as well as a screening, 37 studies were included in the review according to quality criteria (other studies have been excluded due to not matching the current study topic).

Theoretical framework of the study

Throughout this investigation, the two-factor motivation-hygiene theory proposed by Frederick Herzberg in 1950 served as a theoretical foundation for the participants. According to this view, job satisfaction and job discontent are two entirely different notions from each other. According to Herzberg’s thesis, extrinsic variables such as organizational policy, supervision, remuneration, interpersonal connections, and working circumstances might help people feel more satisfied at their jobs, but they do not always do so. Intrinsic motivators, such as success, recognition, responsibility, and promotion, on the other hand, can have a beneficial influence on job satisfaction (Jamieson et al.,2015).

To explain the contrasts between variables that are real motivators for individuals (for example, acknowledgment for a job well done, possibilities for promotion or development, and demanding and gratifying work), as opposed to hygiene or maintenance factors, Herzberg used the term “true motivators.” Salary, supervision quality, interpersonal interactions with colleagues, and excellent working conditions are all examples of hygiene or maintenance variables to consider in the workplace (Herzberg, 2017). Hygiene elements, according to Herzberg (2017), even though they prevent workers from getting unhappy, do not serve as genuine motivators. When it comes to health and safety, extrinsic elements are the most common and can rarely be addressed by employee actions; Hygienic considerations do not drive employees. Motivators are most frequently intrinsic characteristics that are associated with higher levels of work fulfillment. As a result, when managers want to encourage people, they should stress the factors that motivate them (Jamieson et al.,2015).

Job hygiene factors are those aspects of one’s job that are necessary for the presence of motivation at one’s place of employment. These do not contribute to long-term enjoyment since they are not beneficial. In contrast, if these elements are lacking / if these variables are non-existent at the workplace, they contribute to employee unhappiness. In other words, hygiene considerations are those aspects of a work that, when adequate/reasonable, keep employees happy and prevent them from being dissatisfied with their jobs. These aspects of employment are external to the job. Hygiene factors are sometimes referred to as dissatisfiers or maintenance factors, as they are essential to prevent unhappiness from occurring. The job environment/scenario is described by the criteria listed above. Hygiene elements represented the physiological requirements that individuals desired and expected to be met (Jamieson et al.,2015).

According to Herzberg, when it comes to motivational elements, hygiene considerations cannot be considered motivating. Positive contentment is the result of motivating elements. These considerations are fundamental in the workplace. These elements encourage employees to achieve higher levels of performance. These elements are referred to as satisfiers. These are aspects that must be considered when carrying out the work. These factors are perceived by employees as intrinsically satisfying. The psychological requirements that were considered an additional advantage were represented by motivational factors (Herzberg, 2017). Some of the motivating causes are as follows: Recognition – Managers should take the time to acknowledge and commend their staff on their achievements and contributions. Sense of achievement – There must be a sense of accomplishment among the workforces. This varies depending on the work. Some type of fruit must be produced because of the work. Growth and promotional opportunities – In order to drive individuals to perform successfully, there must be possibilities for growth and promotion in the business they work for (Jamieson et al.,2015).

Responsibility – Employees must accept personal responsibility for their job. Managers should empower people by allowing them to take responsibility for their job. They should keep control to a bare minimum while maintaining responsibility. Meaningfulness of work – In order for an employee to perform and be motivated, the task itself must be important, engaging, and demanding for the individual (McEwen & Wills, 2015).

On the basis of the factors in the present investigation, this hypothesis is applied to the current study. The study’s hygiene elements include the significance of the work, which includes doing nursing tasks and avoiding non-nursing chores that are likely to cause discontent with the job. Income and recognition are two more considerations. The recruitment of help nurses or other nurses with other job descriptions who conduct non-nursing jobs in order to avoid work from being unfinished is the focus of this study (McEwen & Wills, 2015).

According to the two-factor theory, managers must place a strong emphasis on ensuring that hygiene aspects are adequate in order to prevent employee unhappiness from occurring. In addition, managers must ensure that the job is engaging and gratifying in order to keep their staff motivated to work harder and achieve higher levels of performance. This philosophy places a strong emphasis on work enrichment in order to inspire people. Work must make the most of the employee’s abilities and capabilities to the greatest extent possible. Concentrating on the aspects that influence motivation can enhance the overall quality of the task (McEwen & Wills, 2015).

Conceptual Framework

The figure illustrates the study conceptual framework; in this study there are three domains which may affect nurses’ job satisfaction (the fourth dependent domain). The first one is non-nursing tasks. The second domain is nursing tasks left undone. The last domain is demographic factors that consist of age, gender, educational level, income level, and marital status. The dependent variable in this study involves nurses’ job satisfaction.

Nursing Workface in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has a chronic lack of Saudi nurses, as well as a high employee turnover rate (Alboliteeh et al., 2017). As a result, foreign nurses make up a substantial component of the nursing workforce in Saudi Arabia, yet little is known about the variables that affect expatriate nurses’ intentions to leave the country (Alshareef et al., 2020). The demands for both native and expatriate nurses will increase in the coming years as the Saudi population increases and healthcare facilities expand (Alboliteeh et al., 2017).

It is precious to note that Saudi Arabia is among the countries with an overburdened healthcare system with high rates of intent to leave. The Saudi healthcare system is challenged by the deficiency of local healthcare professionals. Most health workers are expatriates, which leads to a high rate of turnover and disruption of the workforce. One of the main costs for healthcare providers is the expenditure on qualified medical professionals. A high number of physicians, nurses, and medical staff in Saudi Arabia resort to Western countries due to better facilities and training opportunities (Falatah & Salem, 2018).

The localization of all sectors of the workforce that includes healthcare is one of the 2030 goals in Saudi Arabia. Regardless of efforts to attain this goal, the Saudi Ministry of Health reports that expatriate employees make up 50% of the nursing workforce. (Elmorshedy et al., 2020). The ratio of nurses to the population in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 2017 is 5.7 / 1000 people (Office of Economic Co-operation and Development, 2018). This represents a significant shortfall compared to other countries. The shortage of nurses in the hospital almost certainly leads to poor patient care quality and poor work performance. In this context, the Saudi government has implemented the ‘Saudi National Healthcare Transformation Program (NTP) -2020,’ providing a well-equipped hospital, improving governance in quality of healthcare services, especially among healthcare professionals (Albougami et al., 2020). Currently, nursing is not considered positive in Saudi culture. The government’s attempts to attract more Saudi nurses into the nursing profession and retain them face challenges such as an unattractive work environment, limited choices to balance work and family responsibilities, the attitude of the nursing home, and the associated bad image (AlYami and Watson, 2014). The main reasons why nursing is not considered a profession among Saudi women are related to cultural values, family disputes, non-discrimination between the sexes, the low level of nursing, and the night shift. Therefore, it is ultimately not seen as a suitable career for women (AlYami and Watson, 2014).

Research studies on the issue of nurses’ intention to leave showed that 46.6% of Saudi nurses reported their intention to leave within the next 1-3 years. (Dagamseh and Haddad, 2016). Furthermore, current Saudi regulations for recruitment and saudization continue to increase employee costs due to the limited resources available. The government’s role is significant in the foundation of career-focused educational institutions to increase local health care workers and motivate qualified Saudis to pursue careers. To overcome this gap, the government must apply funding to the private sector and improve employment regulations so that it can attract qualified foreign workers. (Al-Mutairi et al., 2020).

Nursing officials in Saudi Arabia must move quickly to improve nurse care by addressing the nursing shortage, developing initiatives to improve nursing education, and defining scope of practice standards. These pressing concerns must be addressed within the framework of the 2030 vision (Al-Dossary et al., 2018).

Job satisfaction

Due to the possible influence on patient care quality and safety, as well as the fact that low job happiness is a contributing reason for nurses quitting their current positions and the profession, job satisfaction is a global problem (Masum et al., 2016). More data about nurses’ job happiness is emerging, with recent evaluations focused on one component or one geographical location, such as the association between job satisfaction and task delegation, psychological empowerment, workplace empowerment, and nurses’ general job satisfaction (Jang & Oh., 2019; Yarbrough, 2017). A new update based on this current information is required to further understand and highlight the gaps that still exist in the field.

Positive ratings for factors such as organizational policies, salary, and the workplace environment, according to Herzberg and colleagues’ famous two-factor theory, do not directly lead to job satisfaction, but rather to the absence of dissatisfaction. These factors were referred to as “hygiene factors” by the authors. Alternatively, they asserted that work content had a direct and positive impact on a person’s pleasure with their employment, and that this is referred to as a motivating component in the workplace (Herzberg et al., 2017). Research studies have also found that nurses are more happy with their professions when they have the opportunity to incorporate evidence-based practice into their daily routine (Kang, 2016).

Cross-sectional research was carried out in Botswana and included all nurse anesthetists who were working in clinical practice at the time. According to the findings, 36.4 percent of the employees were satisfied with their job overall. Males reported higher levels of work satisfaction than females, by a substantial margin. Additionally, married nurse anesthetists, expatriate nurse anesthetists, nurse anesthetists working in non-referral hospitals, and nurse anesthetists with less than ten years of experience reported considerably higher levels of job satisfaction than the general population. A total of 60.0 percent of nurses expressed satisfaction with security, social services, authority, abilities utilization, and responsibility. In a comparable percentage, they were dissatisfied with their income, working conditions, and opportunities for promotion (Kassa et al., 2021).

Vermeir et al. (2018) conducted a multicenter survey research study on 303 nurses in Belgium to examine the relationship between job satisfaction and communication, as well as their intention to leave. They used the Intent to Work Turnover Scale, the Maslach Burnout Stock Scale, and the visual analog scale to gather their data. According to the study findings, a sample of participants in Flanders saw higher levels of team collaboration and higher levels of work satisfaction. The intention to take time off and the occurrence of burnout were both constrained. Communication satisfaction may be associated with job satisfaction, intention to leave, and burnout at work, according to research. Although the sample for this study has not been determined, it is possible that certain confounders will be uncovered in this investigation (Vermeir et al., 2018).

Mari et al. (2018) conducted a cross-sectional study to identify the characteristics that affect work satisfaction among intensive care unit nurses at King Khalid Hospital in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, using the Job Satisfaction Scale, which was administered to 190 nurses. The survey findings indicated that nurses have a moderate level of job satisfaction. This necessitates the engagement of senior leadership. Nurses’ job happiness is a critical factor to consider when developing new regulations to improve their working conditions. In this study, the researchers did not consider the confounding variables.

In addition, Alostaz (2016) conducted a cross-sectional study to evaluate factors that impact the job happiness of nurses in Saudi Arabia. The scale of job satisfaction was administered to 60 nurses, and the results were analyzed. According to the survey findings, work satisfaction was at a good level. In addition, age was shown to be significantly linked with work satisfaction; older nurses are reported to be more content with their jobs than younger nurses.

Teruya et al. (2019) conducted a cross-sectional study on 163 nursing participants to assess their level of job satisfaction and its relationship with their personal and professional characteristics. The study used a measure of job satisfaction to assess their level of job satisfaction and its relationship with their personal and professional characteristics. There was a positive relationship between the intention to continue working and most of the areas of the job satisfaction questionnaire, except for coworkers and operating processes. There was also a positive relationship between the length of time spent working in the unit and in the organization and the payment of fields, conditional bonuses, and supervision, according to the study findings.

Semachew et al. (2017) conducted an organization-relied census to evaluate job satisfaction levels and domains that influence it among nurses in public hospitals in the Jima region, southwestern Ethiopia, using the McCluskey / Mueller satisfaction scale on 316 nurses. According to the study findings, one-third of nurses reported having a low degree of satisfaction with work. The effect variable is determined by factors such as workload, professional dedication, work environments, and general understanding at work. In the study, there was no discussion of issues related to managing confounders.

Oliveira et al. (2017) conducted a cross-sectional study to examine the relationship between the environment of nursing practices and work satisfaction in the intensive care unit (ICU) using the Nursing Work Index-Revised (NWI-R) on 284 nurses. The findings of the study revealed that there was a low level of work satisfaction. Work satisfaction is related to a variety of factors, including the practice environment, the amount of time spent in the intensive care unit and the willingness to work. As a result of the lack of control of confounders in this investigation, the quality of the study results may be compromised.

Abduelaz and Tahir (2016) conducted a hospital-based descriptive study to demonstrate the comprehensive job satisfaction level and correlate the socio-demographic variables of intensive care nurses with the overall job satisfaction level in Sudan. They used a measure of job satisfaction level administered to 125 nurses to demonstrate the comprehensive job satisfaction level. The findings of the survey revealed that the job satisfaction of nurses varied depending on their age and qualifications, according to the findings. Furthermore, the functional features inherent to outside work environments are just as important to the job satisfaction of an intensive care nurse as the attributes fundamental to the work environment itself. The author of this study did not elaborate on the intrinsic characteristics of the job that were considered in this investigation.

Nursing tasks left undone

Nursing chores that are left undone or missing nursing care, which is defined as the omission or delay of key patient care tasks, are regarded to be a component of the nurses’ work process and should be addressed. Missed nursing care, according to studies, is a global occurrence that has a negative impact on overall patient care quality (Jones et al., 2015). While providing critical patient care, nurses acknowledged feelings of remorse as well as frustration, roboticist, and unethical behavior. Consequently, nursing duties left undone when nurses are present in the work process may have an impact on nurses’ job satisfaction, as evidenced by research (Mandal & Seethalakshmi, 2021).

It has been demonstrated in a growing body of studies that failing to complete nursing chores can result in serious harm to the patient. However, in developing countries, this is still a topic that has not been extensively investigated (Hammad et al., 2021). Patients’ safety may be jeopardized in hospitals when nursing responsibilities go unfulfilled, which is common in hospitals. It has been demonstrated that leaving nursing chores undone is associated with higher levels of nursing adequacy.

Missed nursing care, as well as the environmental and staffing variables that contribute to it, should be closely evaluated by nursing leaders to create strategies to prevent this problem in the future, according to the American Nurses Association (Hammad et al., 2021). Several studies have found that nurses devoting considerable amounts of their time to non-nursing duties are a significant contribution to the number of nursing chores that remain incomplete. In the context of direct patient care, non-nursing duties are any actions that do not necessitate the application of professional nursing talents and are not directly related to direct patient care (Bekker et al., 2015).

Using a cross-sectional study design, Bekker et al. (2015) investigated the relationship between non-nursing responsibilities, nursing activities left undone, and work satisfaction among professional nurses in South Africa. As a result, clerical duties, arranging discharge referrals and transportation, and providing non-nursing care were the three most common non-nursing tasks completed, while the three most common nursing tasks left undone were comforting and talking with patients (62.2%), educating patients and their families (57.0%), and developing or updating nursing care plans/pathways (55.0%).

Furthermore, according to the findings of the study, nursing responsibilities that were left undone were only related with three non-nursing activities, and work satisfaction was shown to be most strongly associated with nursing responsibilities that were left undone. Researchers discovered that professional nurses who fail to complete their nursing tasks have the greatest degrees of work dissatisfaction on the job (Bekker et al., 2015).

Cross-sectional research was conducted to evaluate the degree of missing nursing care in Alexandria, define the forms of missed nursing care, and investigate the variables that contribute to missed nursing care. Following data analysis, it was discovered that the total mean score for missing nursing care was 2.26 out of 5, with the highest mean score given to “Planning” and the lowest mean score assigned to “Evaluation and Vital Signs” (2.64 and 1.96, respectively). The number of patients admitted and cared for in the previous shift, as well as the perception of staffing sufficiency, was found to be strongly linked with missed nurse care. Furthermore, practically all non-nursing care duties as well as most satisfaction aspects exhibited a negative or weak connection with the total amount of missing nursing care time (Hammad et al. 2021).

A cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the extent to which non-nursing tasks and nursing care were left undone on integrated nursing care wards, as well as to examine the relationships between nurses’ burnout, job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and medical errors. The findings were published in the journal Nursing Management. In the study findings, it was discovered that the score for non-nursing chores was 7.32, while the score for nursing care left undone was 4.42. Nurses’ burnout has increased because of an increase in non-nursing responsibilities and a decrease in the amount of nursing care provided. Furthermore, as the amount of unfinished nursing care grew, so did the likelihood of nursing staff turnover, resulting in a rise in the number of medical mistakes (Park & Hwang, 2021).

The researchers also carried out a cross-sectional analysis to find out what other factors are related to variance in the amount of “care left undone” by nurses in Sweden. Their finding found that 74.0 percent of nurses claimed that some care had been left undone during their previous shift. The time of day, the patient mix, the nurse’s role, the atmosphere of the practice, and the number of staff members all have an impact on the amount of unfinished treatment. When comparing shifts where nurses care for six or fewer patients with shifts where they care for ten or more patients, the probability of treatment being left undone is reduced by half. According to the findings of the study, the previously reported association between registered nurse staffing and care left undone has been corroborated. Reports of unfinished care are impacted by the function of the registered nurse. The number of support workers on the job has minimal impact. It is necessary to do more research to determine how these characteristics interact with each other and whether failure to provide treatment is a predictor of poor patient outcomes (Ball & Griffiths, 2016).

According to the findings of the study, non-nursing responsibilities and nursing care that is left undone are all positively associated with nursing burnout, turnover intentions, and the possibility of medical errors in the field of nursing (Park & Hwang, 2021).

To evaluate the relationship between job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing activities left undone among Egyptian nurses, Naiem et al. (2021) conducted a descriptive study. Following a rigorous approach, the subject and methodologies were selected for this investigation. The results of the survey revealed that more than half of the nurses were indifferent, although they expressed a low level of satisfaction with their job as a nurse. In addition, there were five non-nursing professions that were done the most frequently by the nurses who took part in the survey, and these are listed below. Nurses who participated in the investigation left several nursing tasks undone, and this was discovered during the investigation.

A statistically significant difference was found between the job satisfaction of the nurses analyzed and their work in non–nursing activities, as well as between the job contentment of the nurses examined and their chores that were left undone, according to the research conclusions. According to the findings (Naiem et al., 2021), of the study, nurses were less satisfied with their professions since they frequently did non-nursing chores while neglecting to complete some key nursing obligations.

A substantial statistically significant positive connection was found between the non-nursing responsibilities completed by the study nurses and the nursing chores that were left undone in the research. Although there were no statistically significant links between study nurses’ work happiness and their non–nursing activities, there were statistically significant associations between nurses’ job satisfaction and the number of nursing tasks that were left uncompleted (Naiem et al., 2021).

In order to determine the quantity, nature and causes of missing nursing care in the Italian medical care context, a 3-month longitudinal survey was conducted, followed by a cross-sectional study design. The findings revealed that the predictors of missed nursing care were patient ambulation, turning the patient every 2 hours, and delivering medications at the appropriate time, which were the most reported missed nursing care. Unexpected increases in patient load or appearance of severe situations, insufficient personnel, and a significant number of admissions and discharges were among the most frequently cited reasons. According to the findings of the study, adequate nursing care standards must be implemented as soon as possible in medical units that are tasked with protecting vulnerable patients (Palese et al., 2015).

Non-nursing tasks

In recent years, the idea of non-nursing duties has piqued the interest of academics, as these tasks account for anywhere from 35% to 62% (Bekker et al., 2015) of the total nursing shift time and have detrimental effects for both patients and nurses (Bekker et al., 2015). Non-nursing chores have been defined as actions carried out by nurses who are ‘below their competence level’ some years later. Cleaning rooms, delivering or collecting food trays, guiding patients, and providing auxiliary services are all examples of non-nursing jobs that have been recorded in the literature (Grosso et al., 2021).

Nurses have been reported to perform administrative activities in addition to their clinical responsibilities, such as restocking charts and paperwork, answering phone calls, and scheduling appointments. Over time, the definition of “non-nursing jobs” has been broadened to include actions performed by allied health care professionals, which are those who work in the health care field but are not doctors, dentists, or registered nurses (Featherston et al., 2020). Patients are mobilized on Sundays when physiotherapists are not present, according to (Grosso et al., 2019). This is an example of non-nursing work. Furthermore, nurses have responsibilities that go beyond the scope of the medical profession, such as making judgments regarding diagnostic treatments when physicians cannot be present at the patient’s bedside when physicians are absent (Grosso et al., 2019).

There have been four major categories of non-nursing jobs that have been documented: (a) Administration-related tasks; (b) auxiliary tasks, which are tasks that could be delegated to nurses’ aides, assistants, and unlicensed health workers; (c) tasks that fall within the scope of practice of allied health care professionals; and (d) tasks that fall within the scope of practice of physicians (Grosso et al., 2021).

Nursing tasks left undone and job satisfaction

In India, a cross-sectional study was carried out to investigate the association between missing nursing care and nurses’ overall work satisfaction. Researchers discovered that nurses’ job happiness was substantially correlated with missing nursing care, hospital kinds, and educational attainment. These three factors combined explained 27% of the variance in nurse job satisfaction. According to the findings of the study, nurses’ job satisfaction may be improved by using targeted techniques to reduce missing nursing care. Nursing supervisors can utilize missing nursing care as a process indicator to analyze and forecast nurses’ work satisfaction, as well as to improve patient care (Mandal & Seethalakshmi, 2021).

To determine the types and causes for “missing nursing care” among Jordanian nurses, as well as the correlations between “missed nursing care” staffing, intent to quit and work satisfaction, a descriptive cross-sectional approach was investigated. According to the study findings, the most common reason for “missing nursing care” was a lack of available labor resources. A limited number of nurses per shift was shown to relate to a significant degree of’missed nursing care’, according to the findings. In addition to that, nurse managers must address staffing issues that could lead to an increase in the incidence of missed care and have severe consequences for patients, nurses and the business as a whole. To reduce missed care and improve patient satisfaction, nurse administrators could implement evidence-based staffing strategies to control the nurse-to-patient ratio (Al‐Faouri et al., 2021).

In addition, a cross-sectional study was carried out to compare the amounts and reasons for missing nursing care, as well as levels of nurse staffing and levels of job satisfaction between the United States and Lebanon. Several studies conducted in the United States have revealed that a considerable quantity of care is being neglected by patients. The purpose of this study is to identify whether or not Lebanon is experiencing a similar situation and, if so, what the causes are for the lack of nursing care. Nursing care is missing in Lebanon, although at a lower rate than in the United States, according to the findings. Nurses in Lebanon are less satisfied with their jobs than nurses in the United States, and there is no difference between staffing resources being identified as a reason for missed care in the two countries. However, staffing resources were identified as a reason for missed care in both countries (Kalisch et al., 2013).

Another study investigated the influence of missing nursing care on the work satisfaction of nursing professionals via a cross-sectional design. The results of this study found that nursing personnel who reported fewer instances of missing nursing care in the patient care unit where they work reported higher levels of satisfaction with their current position and career. It was also shown that perceptions of staffing sufficiency were associated with both satisfaction factors. Concentrated actions focused on reducing the number of missed care appointments and ensuring enough staffing is required to increase work satisfaction and patient care (Kalisch et al., 2013).

To investigate the incidence of missed nursing care among Czech hospital nurses and the association between job satisfaction of nurses and missed nursing care, the study findings indicated that patient ambulation and emotional support for the patient and/or family were the two nursing actions that were most frequently overlooked. In the poll, nurses expressed their greatest satisfaction with their job as a nurse, while their greatest dissatisfaction was with the amount of collaboration in their unit (Plevová et al. 2021).

In this study, the highest association was identified between contentment with the current job and satisfaction with the profession of a nurse; nevertheless, there was a negative correlation between pleasure with the current position and the overall level of nursing care missed. Plevová et al. (2021) found a statistically significant relationship between the assessment of satisfaction with current employment and the number of nursing care hours lost.

A prospective two-stage panel longitudinal research was conducted in acute hospitals in China to examine changes in quality of care, nurse job outcomes, nursing work environment, non-professional chores, and nursing care left undone during the study. The amount of nursing care that was not completed was measured using 12 categories that addressed important nursing actions. Burnout, discontent, and retention were all reported as consequences of the nursing profession. Nurses (three items) and patients (one item) rated the overall quality of care provided (Liu et al., 2021).

The findings demonstrated that the nursing work environment had improved and that non-professional responsibilities had dropped to a minor extent as a result of the intervention. The average number of nursing care activities that had not been completed had increased from 12 to 14. Nurses who were dissatisfied with their jobs or who intended to quit did so in fewer numbers. According to nurses and patients, the overall quality of treatment has improved somewhat (Liu et al., 2021).

On the impact of changes in hospital organizational elements on quality of treatment, a better nursing work environment was shown to be associated with better nurse job outcomes and higher levels of patient satisfaction. Higher degrees of nurse job burnout were shown to be associated with increased non-professional responsibilities. A reduction in the amount of nursing care left undone was related to a higher nurse-assessed overall quality of care. When more nurses suffered from work burnout and discontent, the quality of care rated by nurses was likely to be worse in such units (Liu et al., 2021).

Conclusion

This chapter illustrated previous literature studies related to the study topic, including job satisfaction, nursing tasks left undone, and the relationship between job satisfaction and nursing tasks left undone.

Methodology

Introduction

This section introduces issues related to material and methods of the study procedures. These methods involve the study design and the approach of a research study. This section also considers illustrating the study population, sample and sampling; inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, data collection instrument; validity and reliability of the study; ethical consideration; and data analysis.

Research Approach

This study employed a quantitative research approach to examine the association between Saudi nurses’ job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing tasks left undone in both government and commercial institutions. The quantitative approach necessitates the use of logic and objectivity to investigate relationships and predict phenomena to make detailed conclusions (Heale & Twycross, 2015). The numeric data derived from a selected study field prompts convergent reasoning to interrogate the research problem at hand. On the other hand, several reasons informed the study’s adoption of a quantitative approach. The technique demands the use of structured research instruments to gather data, which then compels the researchers to select a large sample size to boost representativeness. The study aimed to assess the representativeness of the job satisfaction of nurses who were on non-nursing tasks and nursing left tasks undone in selected hospitals. However, the process required a clearly defined research question to gather objective answers from the respondents, as reasoned by Gerrish and Lathlean (2015).

The quantitative method used a deductive to define the scientific investigation into job satisfaction on nursing and non-nursing tasks left undone among Saudi nurses. The deductive approach necessitates the researcher to study what other scholars have conducted and integrate existing theories to test the emerging hypotheses (Rowell et al., 2017). Therefore, deductive reasoning was essential in theorizing non-nursing tasks and nursing tasks that were not done that affected nursing quality of care and patient care. Furthermore, deductive reasoning enables the study sample to describe the causal relationships between different concepts or variables. The deductive approach shapes a quantitative measurement of the concepts following examination of different literature sources (Harvey & Land, 2017).

After categorizing characteristics and building models to examine the association between job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing chores left undone among Saudi nurses working in government and commercial hospitals, the quantitative research approach offers several benefits. The approach prompts the researcher to explain the data gathered from the participants to foster objective interpretation of the results. On the other hand, the research process enhances replication in other studies (Rowell et al., 2017). The researchers aimed to conduct a study where future different settings could use the standardized data collection frameworks and generalize the concepts to the appropriate target populations. Heale and Twycross (2015).

Cross-sectional Design

The association between Saudi nurses’ job satisfaction, non-nursing chores, and nursing tasks left undone was examined using a cross-sectional study methodology. According to Allen (2017), the design involves simultaneously measuring the outcome and the exposures of the participants. The design involves the recruitment of participants according to eligibility criteria to estimate prevalence in a selected period. The investigator carried out an investigation of the relationship between job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks and nursing tasks left undone among Saudi nurses. Thus, the main goal of the study was to find out how Saudi nurses’ job satisfaction, non-nursing chores, and nursing tasks left undone relate to each other. The results were then used to explain the phenomenon from the viewpoint of other diverse situations.

The application of descriptive cross-sectional studies was valuable in the study. The study is appropriate for screening the research question surrounding the investigation of the relationship between job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing tasks left undone among Saudi nurses at government and private hospitals due to the short time and few resources demanded by the research design (Fain, 2017). The findings should be representative of the entire population. However, the outcomes of the research must be reliable and valid, as Allen (2017) opines. The design made it easier to trace the job satisfaction of nurses as the outcome of interest because it prompted the selection of participants with specific variables. Furthermore, the study did not include any form of variable manipulation, so the researchers collected current and detailed information on job satisfaction among nurses, as Harvey and Land (2017) reasoned. The cross-sectional study presented different advantages to the research process that aimed to generate valid findings.

Cross-sectional research offers different advantages as the research design chosen for quantitative deductive research. The design prompted a fast and inexpensive research process, which would have been difficult to achieve with other research designs, such as qualitative or cohort studies (Allen, 2017). By encouraging the creation of data on examining the relationship between job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing chores left undone among Saudi nurses working in government and commercial hospitals, the study improves reproducibility in subsequent research. The assessment ensured the design generated reliable and transferable findings to the population of nurses hoping for job satisfaction to enhance the nursing quality of care. While the cross-sectional study dictates the evaluation of prevalence as opposed to incidence, the research minimizes selection bias by recruiting participants based on eligibility criteria (Setia, 2016). Conducting the research within a short period defined a discourse on the contextual factors that shape the relationship between job satisfaction, non-nursing, and nursing tasks left undone. It was more tenable to conduct a cross-sectional survey as opposed to a longitudinal research process, which would have required a large allocation of time and budget.

Data Collection Method/s

Electronic Self-Administered Questionnaire

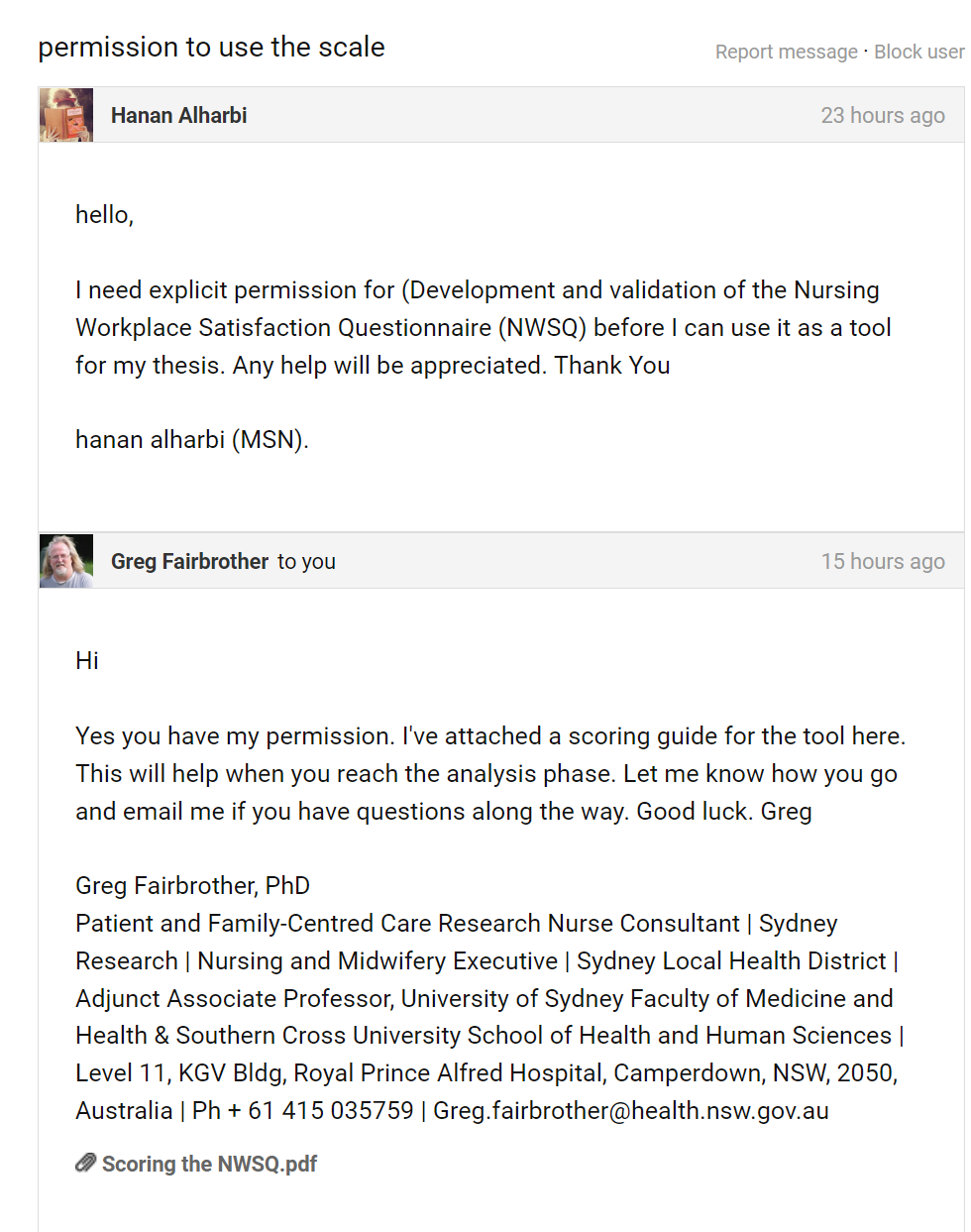

An electronic self-administered questionnaire was used for data collection purposes. The questionnaire consisted of four parts and questions with a scoring system. The first part consisted of a sociodemographic data sheet. The researchers will design the sheet to collect relevant sociodemographic characteristics, such as participants, level of education, and gender. On the other hand, the second part of the electronic self-administered contained questions on a personal job satisfaction survey, developed by Fairbrother et al. (2010). This questionnaire involved 17 questions distributed over 3 categories: 1) job enjoyment; 2) responsibilities at work; and 3) relationships with colleagues. The participants asked to give their responses on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The lowest score for this questionnaire is 17, while the highest score is 85. Participants who have a score of 28 or less will be considered dissatisfied <28. Participants who have score 28-≤57 will be considered as neutral; while participants who have score 58 or higher will be considered satisfied (Fairbrother et al., 2010). The third questionnaire involves the non-nursing tasks scale, developed by ethic et al. (2011). This questionnaire involved 9 questions. The participants asked to give their responses on a three-point Likert scale of never (1), sometimes (2), and often (3) The lowest score for this questionnaire is 9, while the highest score is 27. The fourth questionnaire involved the scale of the nursing tasks left undone, developed by Sermeus et al. (2011). This questionnaire involved 14 questions. The participants asked to give their responses to closed-ended responses (Yes/No). The lowest score for this questionnaire is 0, while the highest score is 14 (Appendix 2).

Instrument of Data Collection

The operational design of the data collection involved a preparatory phase and fieldwork. A review of the past, current local & international related literature was done covering all aspects of the study. The researcher used available books, journals, articles, and magazines to develop a theoretical foundation and get acquainted with the prevailing views on the research problem to investigate the relationship between job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing tasks left undone among Saudi nurses at government and private hospitals. The information from different literature informed the creation of the study tool and guided the researchers in the tool preparation process (Appendix 4) used in the cross-sectional study based on the guidelines of Grove and Gray (2019).

Upon obtaining official permissions to conduct the study and finalizing the data collection tools, the researchers explained the aim to the respondents. The process then involved taking their electronic written consent to participate in answering the four-parts self-administered questionnaire. An electronic questionnaire was prepared using Google Forms to prevent intrusion by non-authorized parties.

The e-questionnaire was shared through emails and WhatsApp groups, on receiving and clicking on the link to enhance the participation rate (Grove & Gray, 2019). The researcher provided the respondents with the discretion to choose the preferred electronic messaging platform to receive the survey link. The participants received the auto directed electronic questionnaire. Subsequently, a set of several questions appeared sequentially, which the participants answered. The time to answer and complete the questionnaire was set at 5-10 minutes. Moreover, using a 5-point Likert scale was essential in interpreting the data gathering process, while the scale further expanded the scale of questioning the respondents.

Instrument Validity and Reliability

The reliability of an instrument is the degree of consistency with which it measures the attribute it is supposed to measure. Reliability was tested through Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, in which the score ≥ 0.70 is considered accepted (Polit and Beck, 2018) as follow:

As shown in the table above, the Cronbach coefficient alpha for the three scales is more than 0.70, which is good and acceptable. thus, the tool is considered reliable and can be applied.

Study Setting

This study was carried out at two hospitals, namely 1) King Fahd Hospital in Almadina (government hospital); and 2) Saudi German Hospital (private hospital). These secondary hospitals provide secondary healthcare services that include medical, surgical, intensive care, pediatrics, obstetrics, gynecology, etc. These hospitals are in Madinah, Saudi Arabia.

Study population

The target population of this study consisted of nurses working in the two hospitals mentioned above. The total number of nurses in these two hospitals is 589.

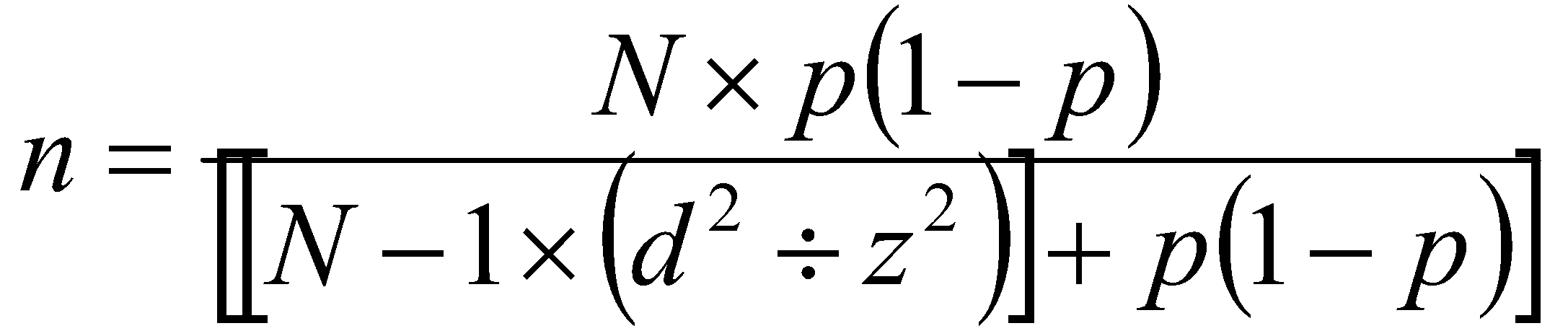

Sample and sampling technique

The study sample was calculated using the Stephen Thompson formula (α=0.05, C.I. 95.0%, N=589). The following formula was used to calculate the sample:

The calculated sample size is 233 nurses. The researcher will use a convenient sampling method to recruit study participants from the two hospitals. The convenient sampling method involves collecting data from the population available at the time of data collection. However, this method ensures a weak representation of the study findings. It is considered a rapid and easy method for data collection. The term “convenience sampling” refers to the practice of selecting participants who are most easily available. People who are easily accessible for convenience sampling may be atypical of the general population, which is a concern with convenience sampling. The risk of prejudice comes at the expense of convenience. Convenience sampling is the most ineffective type of sampling, yet it is also the most widely used way of collecting data.

The selection of a representative sample size used inclusion and exclusion criteria. The researchers Inclusion criteria: Male and female nurses who have at least one year of experience in the hospitals mentioned above will be included in this study. Exclusion criteria Nurses in training and those who have less than one year of experience and those who were not interested in participating in this study were excluded.

Recruitment Method

Participants were recruited from an invitation link using email, and Watsup. Some of the respondents were known to the researcher. According to Nolte et al. (2015), email increases the chances of attaining a high response rate due to the convenience of responding to the questions. The researcher can access valuable information from participants regardless of gender, age, or group.

Data Analysis

To achieve the objective of the study, the researcher used the statistical package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM Version 28) to analyze the data. Demographic variables such as gender, income, education level, and department were managed as categorical variables, while demographic variables such as age were managed as numerical data and changed to categorical. Data entry for demographic variables was done using numerical codes within SPSS software for each demographic variable in the questionnaire.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic variables of the study such as gender, department, educational level, age, income, and hospital type. Frequency and percentage were used in this type of statistics. Regarding the domain of job satisfaction, each question on the scale has five possible answers (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). Thus, the lowest score for each item is 1, while the highest score is 5. The total score for the total domain is 85, and the possible lowest score is 17 [1×17]. The total mean score and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for this scale, which reflect the level of nurse satisfaction.

Moreover, mean percentage for the total scale was calculated through division of the total mean score of scale by 17 then multiplying the result by 100. This percentage reflects the level and status of nurse satisfaction. Regarding the domain of non-nursing tasks, each question in the scale has three possible answers (1, 2, and 3). Thus, the lowest score for each item is 1, while the highest score is 3. The total score for the total domain is 27, and the possible lowest score is 9 [1×9]. The total mean score and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for this scale, in which it reflects the level of non-nursing tasks. Regarding the domain of nursing tasks left undone, each question on the scale has two possible answers (0 for yes answer, and 1 for no answer). Thus, the lowest score for each item is 1, while the highest score is 1. The score of one (No answer) indicates that the task is undone, while the score of zero (Yes) indicates that the task is done. The total score for the total domain is 14 [1 x14], and the possible lowest score is 0 [0 x14]. The total mean score and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for this scale, in which it reflects the level of nursing tasks left undone.

Inferential statistics were also used to answer research questions. The independent sample t-test was used to investigate the differences in the mean score of non-nursing tasks regarding participants’ demographic factors with categorical variables (only 2 categories) such as gender (male/female). One-way ANOVA will be used to investigate differences in the mean score of non-nursing tasks regarding participants’ demographic categorical (more than 2 categories) independent variables such as educational levels (diploma/ bachelor/ master or more) income (<5,000 SAR/ 5,000-<10,000/ 10,000 or more), age groups, etc.

Pearson’s correlation was also used to detect the relationship between nurses’ job satisfaction with nursing tasks left undone and non-nursing tasks. The correlation score was used to indicate the strength of the relationship with the p-value. The p-value was used to indicate the level of significant differences in the mean score in the dependent sample t-test, one-way ANOVA, and Pearson’s correlation test. A significant difference was considered if the p-value is below or equal to 0.05.

Ethical and Administrative Considerations

Pertinent committees approved the study protocol (Appendix 5). Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Almadina Healthcare Cluster (Appendix 5). An explicit permission to use the study on personal job satisfaction level conducted by Fairbrother et al. (2010) was also obtained from one of the authors (Appendix 4). The anonymity of the participants was provided in two ways: participants were asked not to put their names on the questionnaire; all information remained confidential. Besides, they were reassured that participation in this study is voluntary. Also, they were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time if they do not wish to complete it (Appendix 3). Data coding was used to maintain confidentiality and privacy by removing identifying data from personal information.

The study observed the ethical principle of beneficence, privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity of the respondents through different strategies. The study manoeuvres could not relate to any actual or potential harm to the participants after avoiding asking sensitive questions or providing a viable environment for answering the queries outlined in the self-administered questionnaires. The researchers explained the primary aims of the cross-sectional study to all participants. As recommended by Tappen (2016), the research sought information through the electronic self-administered questionnaire with an apparent emphasis on the confidentiality of any obtained information. The strategy prevented any unauthorized or illegal intrusion by third parties.

The study kept the sensitive data private by restricting the framework of the cross-sectional data to the authorized parties as advised by Allen (2017). The questionnaire forms were sent anonymously to the respondents, as Rowell et al. (2017) suggested, to avoid an undue influence on the responses and the overall outcomes of the study. Maintaining the anonymity of the participants was necessary despite prior interactions with the researchers. The researcher coded the number for each participant to anonymize their personal data. Data were encrypted and stored in a password-protected file to limit access by unauthorized persons who lacked express permission to conduct research. The research by Sermeus et al. (2011) included a disclaimer with a statement that the writers do not object to the use of the paper for purposes other than unrestricted use and distribution. The disclaimer suggested that using the authors’ findings is permitted as long as there is a proper citation of the initial writers’ work.

The data was reviewed, coded, and entered into an Excel file and transferred to SPSS v.28 (Statistical Product and Service Solutions 21, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for further analysis. The data collection was employed from the first of February until the first of March 2022. Researchers completed the study within three months, starting on 1/2/2022 until 1/3/2022. The research data was securely stored throughout the course of the research. Lastly, to complete the data disposal procedure, the survey data will be deleted for security and protection purposes.

Results of the Study

Introduction

This chapter illustrates the results of statistical analysis of the data, including descriptive analysis that presents the demographic characteristics of the study sample and answers to the study questions. The researcher used simple statistics including frequencies, means and percentages, also independent sample t-test, Pearson correlation test, and one-way ANOVA were used.

In this chapter, frequencies, means, SD, and mean percentages were used to describe the level participants’ satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing tasks left undone.

One-way ANOVA was used to investigate the differences in the level of participants’ satisfaction regarding categorical (more than 2 categories) independent variables such as age groups and educational levels. An independent sample test was used to investigate the differences in the level of participants’ satisfaction regarding categorical independent variables (only 2 categories) independent variables, such as gender and hospital type.

Sample Distribution according to the Participants’ Demographic Factors

According to the table, the majority (91.3%) of the participants are females, while only 8.7% of them are males. The age of 66.3% of participants is 31 – <40 years, the age of 27.2% of them is 20 – 30 years, while those who are 40 years or older constitute 6.5% of the study sample. Furthermore, 62.0 of the participants have a bachelor’s degree, 32.6% have a diploma, while 5.4% have postgraduate certificates. In addition, 60.9% of participants in the current study are married, 21.7% are single, while 17.4% are either divorced or widowed.

The table shows that more than half (53.3%) of the participants have more than 10 years of experience, 23.9% of them have experience years below 5 years, while 22.8% have experience 6-10 years. In addition, half (50.0%) of participants have income 10,000 SAR or more, while 46.7% of them have income 5,000 -< 10,000 SAR. Furthermore, the majority (92.4%) of participants are working in Governmental hospital, while 7.6% of them are working in private hospital.

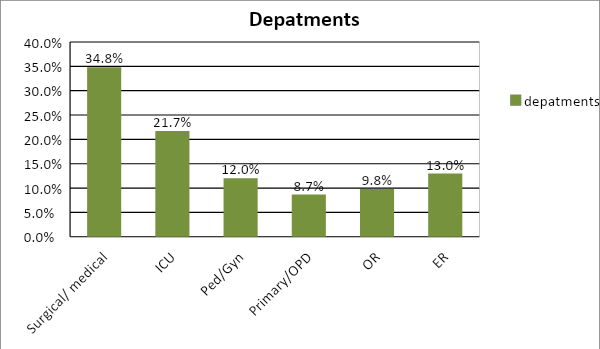

Figure (2) shows that 34.8% of participants are working in medical and surgical departments, 21.7% of them are working in intensive care unit (ICU), while 9.8% are working in operating room (OR).

Nursing workplace satisfaction

The table shows the distribution of each item in job satisfaction among participants in this study. Regarding enjoying job, 10.9% of participants said that they strongly agree that the job gives them a lot of satisfaction, while 20.7 of them strongly disagree about this item. In addition, 23.9% of participants in this study strongly agree about that their job is very meaningful for them, while 14.1% strongly disagree about this item. Furthermore, 15.2% of participants strongly agree about that they are enthusiastic about their present work, while 20.7% of them strongly disagree about this item. Moreover, 13.0% of participants strongly agree about that their work gives them an opportunity to show what they are worth, while 25.0% strongly disagree about this item. The table also shows that 16.3% strongly agree about that in the last year, their work has grown more interesting, while 21.7% of them strongly disagree about this item. Moreover, 17.4% of participants strongly agree about the item “it is worthwhile to make an effort in my job”, while 18.5% of them strongly disagree about this item.

Regarding doing job, 9.8% of participants said that they strongly agree about they have enough time to deliver good care to patients, while 29.3 of them strongly disagree about this item. In addition, 13.0% of participants in this study strongly agree about that they have enough opportunity to discuss patient problems with colleagues, while 27.2% strongly disagree about this item. Furthermore, 16.3% of participants strongly agree about that they have enough support from colleagues, while 16.3% of them strongly disagree about this item.

Moreover, 13.0% of participants strongly agree about that they function well on a busy ward, while 27.2% strongly disagree about this item. The table also shows that 17.4% strongly agree about that they feel able to learn on the job, while 17.4% of them strongly disagree about this item. Moreover, 16.3% of participants strongly agree about that they do not feel isolated from my colleagues at work, while 26.1% of them strongly disagree about this item. In addition, 15.2% of participants feel confident as a clinician, while 18.5 strongly disagree about this item.

Regarding people they work with, 19.6% of participants said that they strongly agree about the item “It’s possible for them to make friends among my colleagues”, while 15.2 of them strongly disagree about this item. In addition, 22.8% of participants in this study strongly agree about they like their colleagues, while 16.0% strongly disagree about this item. Furthermore, 21.7% of participants strongly agree about they feel that they belong to a team, while 15.2% of them strongly disagree about this item. Moreover, 19.6% of participants strongly agree about they feel that my colleagues like me, while 15.2% strongly disagree about this item.

The table shows the mean score and standard deviation as well as the mean percentage of participant workplace satisfaction. The highest mean score for each item is 5, while the lowest mean score is 1. Regarding the subscale “enjoying job”, the highest mean score was observed within the item “job is very meaningful for me”, followed by the items “In the last year, my work has grown more interesting”, and “It’s worthwhile to make an effort in my job”. While the lowest mean score was observed in the item “My work gives me an opportunity to show what I’m worth”.

Regarding the subscale “doing job”, the highest mean score was observed within the item “I have enough support from colleagues”, followed by the item “I feel confident as a clinician”. While the lowest mean score was observed in the item “I have enough time to deliver good care to patients”. Regarding the subscale “people you work with”, the highest mean score was observed within the item “I like my colleagues”, followed by the item “I feel that I belong to a team”. While the lowest mean score was observed on the item “It’s possible for me to make friends among my colleagues”.

Moreover, the table shoes that the item “My job is very meaningful for me” got the highest mean score (3.29), followed by the item “I like my colleagues” with mean score 3.22. The item “I have enough time to deliver good care to patients” got the lowest mean score (2.47). The total mean score of participants’ satisfaction is 48.94 out of 85 (57.5%).

The table shows the classification of each group of participants’ satisfactions with their work. More than half (55.4%) of participants are neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 29.3% of them are satisfied, while 15.2% are dissatisfied.

Non-Nursing Tasks among Study Participants

The table shows the mean score and standard deviation of non-nursing tasks. The highest mean score for each item is 3, while the lowest mean score is 1. The total mean score of doing non-nursing tasks is 22.63 out of 27 (83.81%). The most non-nursing task which is done by participants is “Routine phlebotomy / blood draw for tests” and “Answering phone/ clerical duties” with mean score 2.73, followed by “Transporting of patients within hospital” with mean score 2.71. Moreover, the least non-nursing task which is done by participants is “Delivering and retrieving food trays” with a mean score of 1.57.

Nursing Tasks Left Undone

The table shows nursing tasks which are left undone by participants. The total mean score of the nursing tasks left undone is 8.31 out of 14 (59.35%). The most nursing task which are left undone by participants is “Develop or update nursing care plan” and “Oral hygiene” with a percentage of 68.5%. On the other hand, the least nursing task which is left undone by participants is “Treatments and procedures” with a percentage of 30.4%.

The table shows that there is a significant inverse correlation between the satisfaction of the participants and non-nursing tasks (p<0.05). Increase in non-nursing tasks leads to decrease in participants’ satisfaction. Additionally, there is a significant inverse correlation between participants’ satisfaction and nursing tasks left undone (p<0.05). The increase in left-undone nursing tasks leads to a decrease in participants’ satisfaction.

The table shows that there is a significant direct/positive correlation between doing non-nursing tasks and leaving nursing tasks undone (p<0.05). Increase in non-nursing tasks leads to increase in leaving nursing tasks undone.

Participants’ satisfaction and demographic factors

The table shows that there are no significant differences in the mean score of participants’ satisfaction with regards to their age (p>0.05). In addition, there is no significant difference in the mean score of participants’ satisfaction with regards to their education (p>0.05).

Moreover, there is a significant difference in the mean score of participants’ satisfaction with regard to their marital status (p<0.05). The post hoc test showed that the difference is between married and divorced /widowed in favor of those who are married. Meaning that married participants have significantly the highest mean score of satisfaction.

The table shows that there are no significant difference in the mean score of participants’ satisfaction with regard to their gender (p>0.05). In addition, there is no significant difference in the mean score of participants’ satisfaction with regard to their hospital (p>0.05). Moreover, there is no significant difference in the mean score of participants’ satisfaction with regard to participants’ departments (p>0.05).

The table shows that there is a significant difference in the mean score of participants’ satisfaction with regard to their experience (p<0.05). Post hoc test showed that the difference is between those who have experience >5-10 years and those who have experience more than 10 years in favor of those who have experience more than 10 years; meaning that those who have experience more than 10 years have significantly the highest mean satisfaction score.

In addition, there is a significant difference in the mean score of participants’ satisfaction with regard to their income (p<0.05). Post hoc test showed that the difference is between those who have income 000 -< 10,000 SAR and those who have income 10,000 SAR or more; meaning that is, those who have income 10,000 SAR or more have significantly the highest mean satisfaction score.

The table shows that there are no significant differences in the mean score of non-nursing tasks with respect to the age (p>0.05). Furthermore, there is no significant difference in the mean score of non-nursing tasks with respect to the marital status (p>0.05).

Moreover, there is a significant difference in the mean score of non-nursing tasks with regard to participants’ department (p≤0.05). Post hoc showed that the difference is between ICU department and Gynaecology and paediatric department in favour to those who work in ICU. Meaning that nurses who work in ICU was the most group who are working non-nursing tasks in the hospital.On the other hand, there is a significant difference in the mean score of non-nursing tasks with regard to participants’ education (p<0.05). Post hoc showed that the difference is between bachelor and post-graduate in favour to those who have bachelor degree. Meaning that nurses who have bachelor degree the most group who are working non-nursing tasks in the hospital.

The table shows that there is no significant difference in the mean score of non-nursing tasks regarding to participants’ gender (p>0.05). In addition, there is no significant difference in the mean score of non-nursing tasks with regards to the participants’ hospital (p>0.05).

The table shows that there is a significant difference in the mean score of non-nursing tasks with regards to the participants’ experience (p<0.05). A difference between those with more than five to ten years of experience and those with more than ten years of experience was found by post hoc analysis, favoring those with more than five to ten years of experience. This indicates that the majority of nurses performing non-nursing duties in hospitals are those with more than five to ten years of experience.

In addition, there is a significant difference in the mean score of non-nursing tasks with regards to the participants’ income (p<0.05). The difference between participants with incomes between 5,000 and 10,000 SAR and those with incomes over 10,000 SAR was revealed by post hoc analysis, favoring those with incomes between 5,000 and 10,000 SAR. This indicates that the majority of nurses who perform non-nursing duties in hospitals are those with incomes between 5,000 and less than 10,000 SAR.

The table shows that there is no significant difference in the mean score of tasks left undone with regard to the participants’ age (p>0.05). In addition, there is no significant difference in the mean score of tasks left undone with regard to the participants’ education (p>0.05).

On the other hand, there is a significant difference in the mean score of tasks left undone with regard to participants’ marital status (p<0.05). Post hoc showed that the difference is between divorced and married in favour to divorced. Meaning that divorced nurses are the most group who leave tasks undone. Moreover, there is a significant difference in the mean score of tasks left undone with regard to participants’ working department (p<0.05). Post hoc showed that the difference is between Gynaecology and paediatric and ICU in favour to ICU. Meaning that ICU nurses are the most group who leave tasks undone.

The table shows that there is a significant difference in the mean score of tasks left undone with regard to the participants’ gender (p<0.05). Male participants leave tasks undone more than female nurses. On the other hand, there is no significant difference in the mean score of tasks left undone with regard to the type of hospital (p>0.05).

The table shows that there is a significant difference in the mean score of tasks left undone with regard to the participants’ experience (p<0.05). According to post hoc analysis, there is a difference between individuals with more than five to ten years of experience and those with more than ten years, with the former having more experience. This indicates that nurses with more than five to ten years of experience are the most likely to neglect their work.

In addition, there is a significant difference in the mean score of tasks left undone with regard to the participants’ income (p<0.05). Post hoc analysis revealed that there is a difference between participants with incomes between 5,000 and 10,000 SAR and those with incomes over 10,000 SAR, favoring those with incomes between 5,000 and 10,000 SAR. In other words, nurses who earn between 5,000 and 10,000 SAR are the most likely to neglect their work.

Discussion

Introduction

Investigating the relationship between Saudi nurses’ job satisfaction, non-nursing tasks, and nursing chores left undone at government and commercial hospitals is the primary goal of this study. This chapter is concerned with the discussion of the study results that have been revealed in the previous chapter. Discussion was held in several domains related to job satisfaction; non-nursing tasks; nursing tasks left undone; correlation between job satisfaction and nursing tasks left undone.

Discussion was initiated by comparing the current study results with the previously published results to discuss similarities and differences. Moreover, the researcher opinion was considered during the discussion, in which the researcher considered her opinion on the current results.

Nursing workplace satisfaction of participants

The results showed that the total mean score of participants’ satisfaction is 48.94 of 85 (57.5%), and more than half of the participants are neither satisfied or dissatisfied, 29.3% of them are satisfied, while 15.2% are dissatisfied. The current results are in line with the results of Ahmed et al. (2020), which revealed that more than half of the participants were neutral (neither satisfied or dissatisfied). The results of the current study also revealed that only 29.3% of the nurses were satisfied; this percentage is considered unsatisfactory since less than half are satisfied.

These findings might be explained by the possible stress caused by the workload of the nurses who participated in the study in the selected hospitals. Nursing, on the other hand, is a difficult profession and this stress will increase if you perform evening and night shifts in the same shift pattern (Fallahnejad et al., 2016). Nurses’ energy is depleted by bodily discomfort and emotional consumption, which affects their performance and causes them to be in a bad mood or feel bad about themselves, as well as decreases their job satisfaction. This discomfort is caused by nurses performing non-nursing tasks and leaving their original work unfinished (Schwendimann et al., 2016).