Introduction

The recorded success in the field of healthcare is attributable to the involvement of key stakeholders to identify emerging evidence and utilize it in different medical settings. The concept of continuous improvement guides clinicians to focus on the changing needs of patients and respond to them accordingly. These initiatives have led to the development of the evidence-based medicine (EBM) field. Different stakeholders partner to make EBM a reality, introduce superior clinical interventions, and present scientifically proven procedures to transform patients’ experiences. However, some gaps exist that make it impossible for health professionals and government agencies to integrate fully in the field of healthcare practice, such as policy constraints. With EBM implemented to transform the healthcare sector, key stakeholders need to collaborate and address key policy gaps in the Affordable Car Act (ACA) to continue integrating emerging evidence to meet patients’ medical needs.

Evidence-Based Analysis Process

A proper understanding of EBM process is essential since it allows stakeholders to identity and integrate emerging evidence in clinical practice. In most cases, EBM follows five unique steps that allow clinicians to identify emerging evidence and apply it in different healthcare settings. The first phase entails the conversion of the acquired into questions that are relevant and answerable. This approach guides the involved professional to understand the key issues and consider how to address them. The second step is to gather the available evidence and identify the most appropriate to answer the outlined questions (Fedorowicz & Aron, 2021). The third stage is to appraise the available information to ensure that it is useful and valid. The fourth stage entails the application of the outcomes from the completed appraisal into the targeted clinical practice. The final phase is the evaluation of the recorded outcomes.

Leaders and educationists in healthcare encourage professionals to identify the best ways to develop the necessary EBM skills and improve their practice. The resultant ideas and guidelines would be essential towards improving the quality of care available to different patients. The process goes further to encourage key stakeholders to take the process of critical thinking seriously (Horne, 2020). By following the outlined phases and principles of EBM, practitioners can utilize the best evidence from research and implement it accordingly to transform the quality of medical services available to the targeted patients.

Key Players in EBM Policy

EBM policy attracts different stakeholders whose contributions and activities are essential towards improving the overall efficiency of medical practice. The first one is that of hospitals and related healthcare facilities. These institutions attract professionals who are required to implement the ideas and eventually ensure that more patients receive high-quality and personalized medical support (Horne, 2020). They share emerging ideas to improve care delivery and improve the outcomes of the targeted patients. The second category of players includes researchers who complete a wide range of studies to generate ideas and apply them to solve most of the recorded challenges or issues. Their research findings and observations are essential since they make the work of other stakeholders easier whenever finding emerging clinical evidence and guidelines.

The government is another key player that provides guidelines for strengthening policy agenda, planning care delivery, and coordination most of the activities in the healthcare sector. Patients are key stakeholders since they cooperate with practitioners and healthcare professionals to achieve positive health results (Fedorowicz & Aron, 2021). Nurses, physicians, and clinicians are key partners in EBM since they support the provision of emerging ideas and implementation of noted evidence in various healthcare settings.

EBM Levels of Evidence

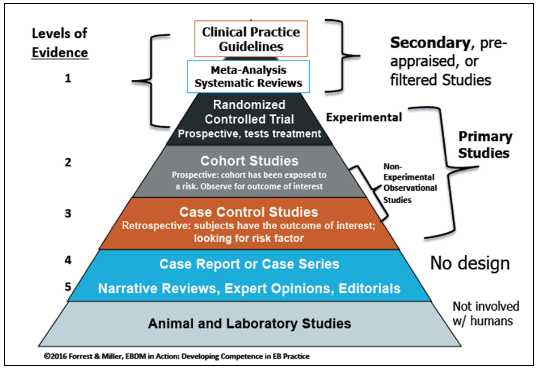

Different unique levels of evidence exist that researchers should take into consideration whenever focusing on EBM practice. Level I entails evidence acquired from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and evidence-based practice obtained from systematic reviews of different RCTs (Li et al., 2019). Level II presents information gained from one or more properly designed RCT. Level III describes evidence emerging from properly designed controlled trials that do not include quasi-experimental approaches. Level IV comprises of evidence coming from cohort studies or case controls (Fedorowicz & Aron, 2021). Level V includes evidence coordinated reviews of qualitative and/or descriptive analyses. Level VI is evidence from qualitative or descriptive studies. Level VII represents evidence from expert communities or authority opinion.

To describe these levels further, analysts rely on the use of a pyramid that helps examine the strength of various levels and the related research designs. For instance, the top of the evidence pyramid usually include research studies characterized by higher or stronger internal validity (see Fig. 1). In most cases, such investigations tend to be associated with strong scientific inquires, quantitative analyses, and reviews (Basu, 2021). The lower sections of the pyramid would include findings or evidence gained from expert opinions or observational investigations (see Fig. 1). At the bottom include studies that do not contain human subjects but succeed to offer significant evidence, such as laboratory investigations (Fedorowicz & Aron, 2021). Stakeholders and professionals need to consider these levels whenever looking for new evidence and applying it to transform care delivery and improve medical practice.

Constraints of the ACA on Evidence-Based Medicine: Analysis

EBM policy is an area that continues to encounter numerous obstacles due to the nature of the existing laws. For instance, the selected case, “Constraints of the ACA on Evidence-Based Medicine”, reveals that unique gaps exist in the manner in which the Medicare Advisory Payment Commission and the Department of Health and Human Services consider emerging evidences. Such gaps affect the process of evidence implementation within the workings of the ACA (Li et al., 2019). The model is designed in such a way that it discourages different entities and stakeholders from pursuing emerging ideas in clinical practice and utilizing them to inform reimbursements for various care delivery services.

The current model places significant constraints in the manner in which Medicaid and other agencies utilize comparative evidence and research findings. However, ACA offers additional specifications. The Secretary cannot utilize emerging evidence from research to make unique determinations regarding the major Medicare coverage. The Secretary is capable to deny additional coverage on services or items even if they are based on comparative research. The policy goes further to discourage the use of findings from clinical research findings to determine coverage, incentive programs, and reimbursements (Basu, 2021). Additional requirements indicate that the established programs do not accept research findings as coverage recommendations, guidelines, or payments.

Based on the presented case, it is evident that stringent guidelines exist that define how the ACA specifies the procedures of acquiring evidence and their eligibility. In incentive programs and the promoted reimbursements, as provided under Title XVIII, it is notable that the use of evidence remains limited (McLaughlin & McLaughlin, 2014). Specifically, the emerging insights or findings from research would not help inform practice guidelines, policy issues or recommendations and payments.

Five grades of policy recommendations are outlined for application in EBM in accordance with the outlined levels of evidence. Based on this requirement, it is notable that the Secretary would only be in a position to use emerging findings and evidence from research completed in accordance with Section 1181. The emerging insights would guide the Secretary to make meaningful determinations when it covers to coverage as outlined in Medicare’s Title XVIII (McLaughlin & McLaughlin, 2014). The Secretary should ensure that the selected evidence emerges from a transparent process associated with public comment and takes into consideration its impact on subpopulations.

Conclusion

EBM has become a useful field that guides governments, health professionals, patients, and researchers to appraise emerging questions and consider emerging insights to develop better ideas and findings. The recorded attributes are capable of guiding these key stakeholders to make informed clinical decisions. The approach provides a detailed strategy for completing clinical research and delivering new knowledge that could be applied to improve the health experiences and outcomes of patients. The use of systematic reviews and studies makes it possible for health professionals to remain involved and acquire additional insights that play a significant role towards transforming the overall integrity of the healthcare sector. EBM helps promote the concept of critical thinking while supporting the elimination of interventions that are harmful or incapable of affecting health outcomes. When clinicians remain open-minded and ready to identify emerging methods, chances are high that more countries would record improved healthcare quality.

References

Ascension. (2022). Evidence-based practice: Levels of evidence and study designs. Web.

Basu, S. (2021). Evidence-based health policies and its discontents – Comparative global and Indian perspectives with a focus on the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 46(3), 363-366. Web.

Fedorowicz, M., & Aron, L. Y. (2021). Improving evidence-based policymaking: A review. Urban Institute.

Horne, J. R. (2020). Are we losing sight of the meaning of “evidence-based nutrition?” International Journal of Public Health, 65, 513–514. Web.

Li, S., Cao, M., & Zhu, X. (2019). Evidence-based practice: Knowledge, attitudes, implementation, facilitators, and barriers among community nurses—Systematic review. Medicine, 98(39), 1-9. Web.

McLaughlin, C. P., & McLaughlin, C. D. (2014). Health policy analysis: An interdisciplinary approach (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.