Abstract

Depression or Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) remains a significant concern for modern-day healthcare, including that of the US. In primary care, the issue of MDD screening is especially acute. Based on the recent literature, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a superior method of depression screening. This project offers to implement PHQ-9 at a specific primary care clinic with the goal of checking its ability to improve depression screening accuracy. The present paper offers an overview of the literature on the topic and details an action plan with a timetable based on the IOWA model and Kurt Lewin’s model. Then, the results of the project are presented and discussed. The findings suggest that because of the small sample, the results cannot be used to claim that PHQ-9 is supported by the project, but its efficacy is not disproven either.

Introduction

Clinical Problem

As a treatable mental illness with significant negative effects, MDD benefits from early diagnostics, but to this day, it is not entirely clear which approach to screening is the most effective (Levis et al., 2020). It is recommended to use a standard screening tool (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2016). Furthermore, there exists the problem of insufficient screening in primary care (American Psychiatric Association, 2017). As a result, the implementation of a standardized tool like the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) in practice is both in line with the current recommendations and can produce important findings on the matter.

Significance

According to the American Psychiatric Association’s (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition), Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a very common chronic condition characterized by “depressed mood… markedly diminished interest or pleasure… feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt,” which tends to also involve weight loss, changes in sleep patterns, fatigue, “psychomotor agitation or retardation… diminished ability to think or concentrate,” as well as suicidal ideation (pp. 160-165). By definition, MDD causes “significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning” (APA, 2014, p. 161), which explains the need to address this condition (World Health Organization, 2020).

According to Fekadu et al. (2017), depression may be caused by a combination of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors, including stressors (for example, stress) and vulnerabilities (for instance, genetic predisposition). Stahl (2013) points out the importance of neurotransmitters for mood disorders, specifically “norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin… [which] comprise what is sometimes called the monoamine neurotransmitter system.”

Hypothetically, depression and other mood disorders might result from the various dysfunctions related to these three neurotransmitters, which might explain the mechanisms of the work of antidepressants that include predominantly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) (Stahl, 2013).

As reported by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2018), one in 23 Americans experiences MDD; according to the National Institute of Mental Health [NIH] (2019), 7.1% of adults in the US have experienced at least one episode of the disorder, with younger people (aged between 18-25) being especially susceptible to it (13% of them having experienced MDD). Moreover, 64% of those cases involved severe impairment (NIH, 2019). According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] (2020), substance use is prevalent among people with MDD, with 21% of people diagnosed with MDD being also diagnosed with a substance use disorder. Furthermore, among people with MDD aged 18-22, 14% had a suicide attempt in the year preceding data collection (Li et al., 2017; SAMHSA, 2020).

Every year, 210.5 billion dollars is estimated as the economic burden associated with major depression (Ferenchick et al., 2019). This includes missed workdays, and decreased work productivity with an upsurge in medical costs (CDC, 2018). In other words, MDD is a health issue that decreases the quality of life, can lead to severe outcomes, including suicidal behaviors, tends to cost a lot, and is relatively widespread, especially among younger populations. As a result, the problem of MDD is very critical and important to address.

Definition of Terms

PHQ-9 is a depression-focused questionnaire that contains 9 Likert-scale questions and is aimed at both determining the presence of MDD and quantifying its severity and symptoms (Ferenchick et al., 2019). PHQ-2 is a shorter version with only two questions meant to determine the need for further screening for MDD, which is typically carried out with the help of PHQ-9 (Ferenchick et al., 2019).

PICOT Definitions

- (P) Among adults, 18- 65 years old,

- (I) will the implementation of an evidence-based clinical screening tool for MDD in the form of PHQ-9

- (C) compared to semi-structured interviews,

- (O) improve the psychiatry referral-based accuracy of diagnosing MDD?

The selected population incorporates diverse subgroups that demonstrate the different prevalence of depression, and it includes the one with the greatest prevalence of MDD, that is, adults (SAMHSA, 2020). Furthermore, the population does not include ages that could be considered vulnerable (underage people and older populations). Although younger adults are more prone to depression, it is not proposed to focus on them.

The use of PHQ questionnaires for depression screening is a common and well-evidenced practice (Arrieta et al., 2017; Ferenchick et al., 2019; Hartung et al., 2017; Indu et al., 2018; Korenke et al., 2016; Levis et al., 2019; Levis et al., 2020; Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017; Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019). It has been proven to be suitable for different populations (Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017; Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019), while consistently showing high reliability and validity, as well as sensitivity and specificity (Ferenchick et al., 2019). Given that the use of a standardized screening tool is recommended by the relevant guidelines (APA, 2016), the selection of this evidence-based intervention is reasonable.

Research suggests that PHQ questionnaires are reliable and valid tools for screening for depression, which is likely to be more effective than other methods, especially semi-structured interviews, which are currently used by the Orlando clinic (Ferenchick et al., 2019; Korenke et al., 2016; Levis et al., 2019; Levis et al., 2020; Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017; Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019). Therefore, the expected outcome of an improved MDD diagnosing accuracy is reasonable and supported by the relevant data.

Theoretical Frameworks and Their Definitions and Integration

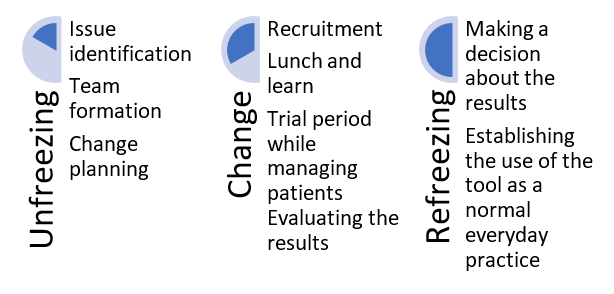

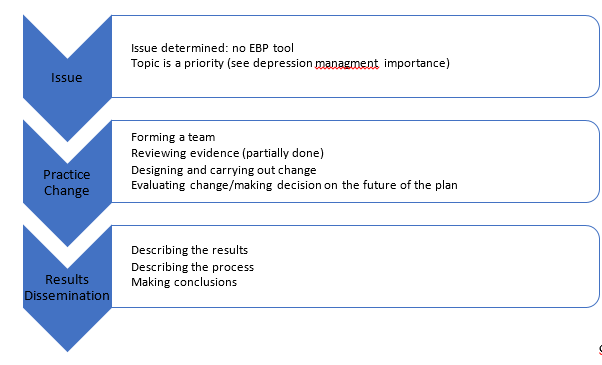

The theoretical frameworks that were used include Kurt Lewin’s Change Model, as well as the IOWA Model of Evidence-Based Practice. The integration of the two models is presented in the chart below based on the works of the Iowa Model Collaborative et al. (2017) and Lewin and Gold (1999).

Review of the Evidence

Search Method

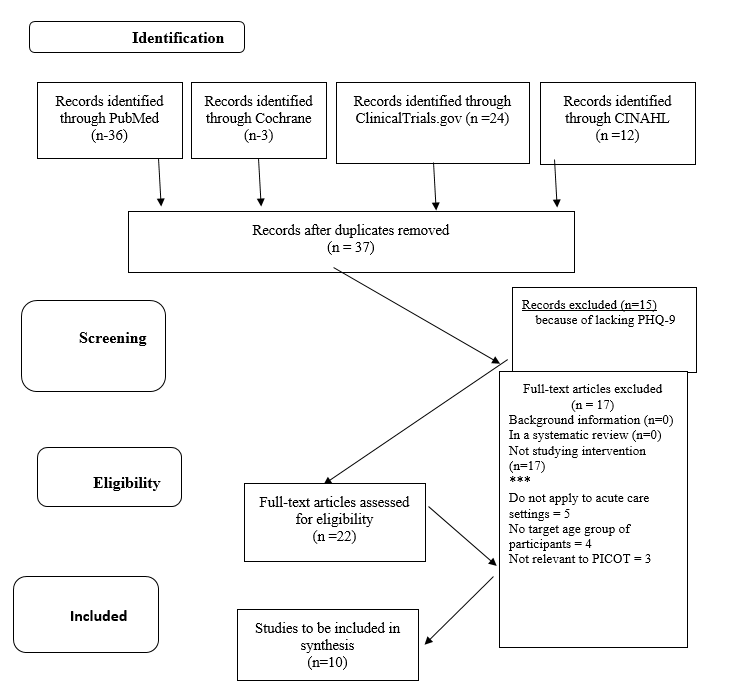

A systematic search was predominantly based on selected keywords, which included the names of the studied tools, in particular, “Patient Health Questionnaire,” as well as terms like “effectiveness, validity, reliability.” Databases that have been searched included Cochrane library, Medline/PubMed, CINAHL and ClinicalTrials.gov. Only recent (2015-2020) peer-reviewed articles in English were considered.

The strategy consisted of employing the keywords to determine the sources that were likely to contain required information based on their titles and abstracts; duplicates were removed throughout the process. Upon the completion of the duplicate removal, the abstracts of 37 articles were screened to determine the articles that would not be suitable for the project because of the lack of focus on the studied topics. After that, full texts of the remaining articles were accessed (22), and the articles that did not fit the requirements of the study were removed. The process did not involve excluding articles based on their methodology or design, which resulted in a selection of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses and other types of studies. Figure 2 represents the process in detail.

Search Results

Table 1 represents the articles of interest to the PICOT, amounting to 10 articles (5 Level I, 3 Level II, and 2 Level IV based on Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt’s (2019) levels of evidence). Additionally, the Practice Guidelines for the Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults by APA (2016) can be mentioned since they establish the importance of screening for MDD. As pointed out by certain literature reviews, including that by Ferenchick et al. (2019), this standard does not exist in all countries since screening is often viewed as the spending of valuable resources, which is not guaranteed to result in positive outcomes. However, for a project carried out in the US, a US guideline is an appropriate selection. Thus, the search results yielded a total of 1 related guideline and 10 relevant articles.

Analysis

The evidence presented in the sources can be reviewed in the following manner. First, each source will be considered in detail. Then, the strengths and limitations of the evidence will be presented. Eventually, a summary will be offered as a form of evidence synthesis. The articles of interest include those by Levis et al. (2019), Levis et al. (2020), Kamenov et al. (2017), Munoz-Nevarro et al. (2017), Korenke et al. (2016), Villarreal-Zegarra et al. (2019), Ferenchick et al. (2019), Fekadu et al. (2017), Ramanuj et al. (2019), and Denson and Kim (2018) (see Table 1 for a review of the levels of evidence).

Table 1. Level of Evidence for Included Sources.

The objective of Levis et al. (2019) was directly in line with that of the PICOT; specifically, the authors aimed to investigate the accuracy of PHQ-9 in terms of MDD screening. Based on the data of 17357 people (from 58 datasets), with the help of statistical analysis, the authors found that at a cut-off score of 10, the sensitivity (0.88) and specificity (0.85) of the tool were exceptionally high, while across 5-15 scores, sensitivity was also high enough to be significantly higher than that of semi-structured interviews, with specificity being similar. Greater sensitivity was found for older patients than for younger ones. The authors reported that their findings were unique in terms of comparing PHQ-9 to different types of depression screening interviews and that more research was required to assess the effectiveness of depression screening.

Levis et al. (2020) performed a meta-analysis with the purpose of determining the accuracy of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9. They included 44 studies (n=10627) from sources like MEDLINE and PsycINFO, which focused on the comparison of PHQ-2 scores with MDD diagnoses. The authors used a bivariate meta-analysis, and they found that the sensitivity of PHQ-2 scores was not different from those of PHQ-9 scores, with the specificity of the combination of the two is 0.87, which was higher than the use of PHQ-2 alone. The authors used that statement as a conclusion to their work, further suggesting that the research on the topic was not yet sufficient for definite recommendations, which led them to propose the need for additional research to determine the comparative effectiveness of different approaches to MDD screening.

Kamenov et al. (2017) presented a systematic literature review (n=247 studies), which was also combined with an expert survey and patient interviews (n=130 and 11 respectively) with the goal of determining recommendations for future research in the field of depression management. The authors found the relevant literature to be lacking, in particular, because of its focus on symptomatic outcomes and a lack of attention to personal factors in depression management. The authors advocate for a more personalized approach with improved measurement of depression management processes and outcomes. The paper helps to situate the current research and offers some insights into the limitations of the current literature.

Munoz-Nevarro et al. (2017) intended to address the issue of MDD being underdiagnosed in Spain by determining the effectiveness of PHQ-9 when applied to Spanish primary care patients. With a relatively small sample of 178 adult people, the article compared PHQ-9 to structured interviews, demonstrating that with the cut-off of 10 points, the sensitivity of the tool amounted to 0.95 and specificity to 0.67. At 12 points, sensitivity dropped to 0.84 but specificity increased to 0.78, and with the help of the structured interview, sensitivity and specificity of 0.88 and 0.8 were achieved. The blinded trial was concluded with the recommendation of using PHQ-9 as a satisfactorily performing tool. The authors also pointed out that their specificity findings were not exactly in line with prior research, which typically demonstrated higher levels of specificity.

Korenke et al. (2016) focused on the analysis of a combination of PHQ-9 and an anxiety scale to determine its parameters. Based on the data from three RCTs, the reliability, validity, standard error, and sensitivity of the tool were considered. The results suggested that all three trials showed high reliability (0.8 to 0.9), convergent validity (0.7-0.8), and sensitivity; construct validity was also acceptable (0.4-0.6). The authors pointed out that the sample was rather homogenous and not very large, which is why further study of the new tool is required, but still, the current evidence suggests that the application of PHQ-9 in connection with other tools may be a valid screening approach.

In order to analyze the PHQ-9 application to the Peruvian population, Villarreal-Zegarra et al. (2019) carried out a secondary data-based trial (n=30,449) with internal consistency analysis as the main analytical approach. The findings suggested that the reliability of the questionnaire was “optimal” (0.87), which suggested that its application to the population was appropriate and capable of allowing comparisons between different groups within it. The authors also highlighted the fact that the results of their investigation were generally in line with those derived from other literature, which further supports the use of PHQ-9.

Ferenchick et al. (2019) are the authors of a two-part review that focuses on depression screening and management. In this section, depression screening was reviewed based on a systematic analysis of the literature. It included some general information about depression before considering the topic of screening with a focus on the existing guidelines. The findings of the reviewed studies further suggested that just screening was not enough to improve the quality of care, but collaborative care was shown to be an effective intervention provided that screening was applied.

In other words, based on admittedly limited evidence, it is important to proceed to treat patients after screening for positive effects, in which case non-screened patients are going to demonstrate less progress than screened ones. The authors generally recommend more research on the topic while pointing out that the validity, reliability, and brevity of PHQ-9 have been long established based on evidence that keeps being supported to this date. The general consensus is that the sensitivity of the tool is 80% and the specificity is 92%. Consequently, PHQ was recommended by the authors for use in primary care.

In the second part of the study, Ramanuj et al. (2019) provided some general information about depression, proceeding to consider the process of depression management. Based predominantly on RCTs, the authors specify existing treatments for MDD, pointing out the importance of training for primary care providers. This article helped to contextualize the project and figure out the focus on training providers.

Included in the Programme for Improving Mental healthcare (PRIME), the article by Fekadu et al. (2017) aimed to assess MDD recognition levels in Ethiopia with the eventual aim of comparing the findings to those that would be collected after training was conducted. The study’s methods consisted of a cross-section survey (n=1014), and it employed a validated PHQ-9 to determine depression in the population.

The latter showed a prevalence of 11.5%, only 5% of which received the diagnosis from the clinicians. In the end, the authors concluded that the absolute majority (98%) of depression cases were not detected by Ethiopian clinicians, suggesting that training for them would be required. It should be pointed out that the authors did not consider PHQ-9 “a gold standard” in depression screening, but they explained their choice extensively with the help of the relevant literature, pointing out its internal consistency and reliability, as well as sensitivity and specificity. The article shows that PHQ-9 has been used in practice and research to produce relatively objective depression screening findings while also highlighting the importance of training providers for MDD screening.

Denson and Kim (2018) aimed to determine the perceptions of providers in primary care related to the work with pharmacists, as well as to assess the gaps in MDD management in the same setting. The method consisted of a retrospective chart review (n=6796) and surveys with providers (n=17). The findings included demonstrating that PHQ assessments were offered to 63% of the whole population, with PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 providing differing assessments. Thus, only 69% of positive PHQ-2 assessments had also positive PHQ-9 assessments, and in addition to that, many (76%) of the people who had positive PHQ-9 assessments did not receive an intervention.

The providers recommended including psychiatric pharmacists in PC. Thus, the authors concluded that gaps were present in the studied settings while explaining the consecutive use of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 by the previously established effectiveness of both, with the former serving as a prerequisite for the latter. The article provides some evidence about the issues associated with depression screening and also offers some secondary data on the effectiveness of PHQ-9. It also highlights the differences between PHQ-2 and PHQ-9, demonstrating the utility of employing the latter.

Synthesis of the Evidence-Based on the presented evidence, the following conclusions can be made. Relatively ample evidence on the effectiveness of PHQ-9 exists, which is shown by a recent literature review (Ferenchick et al., 2019), as well as several primary sources that either focus directly on the tool or on its combination with other tools (Korenke et al., 2016; Levis et al., 2019; Levis et al., 2020; Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017; Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019).

On average, the tool is shown to have high validity, reliability and specificity, although Munoz-Nevarro et al. (2017) found that when applied to a Spanish population, the tool showed rather low specificity. Still, the majority of the findings demonstrate that the parameters of PHQ-9 would be reaching 0.8-0.9 in most cases. Overall, it appears that PHQ-9 should be capable of improving the accuracy of MDD diagnosing. However, it should be pointed out that the topic remains understudied, and more research is needed for conclusive statements (Denson & Kim, 2018; Fekadu et al., 2017; Ferenchick et al., 2019; Levis et al., 2020; Ramanuj et al., 2019).

Additionally, the research showed that training and follow-ups are a requirement for positive outcomes associated with PHQ screening (Ferenchick et al., 2019; Ramanuj et al., 2019). PHQ-2 is shown to be similar to PHQ-9 but a prerequisite to it, which affects its ability to detect depression cases (Denson & Kim, 2018). Overall, the presented data would be enough to justify the selected intervention, explain and contextualize the clinical problem, and provide grounds for the processes required, especially as related to training.

Strengths and Limitations of the Evidence

The major limitation of the presented evidence is that only a few articles provided primary evidence of the usefulness of PHQ-9 (Levis et al., 2019; Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017; Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019). The meta-analyses provided extremely strong evidence, which included a large number of participants; however, their samples were rather homogenous (Levis et al., 2019). The systematic reviews focused on recent and high-quality articles, which boosted the quality of their evidence; however, those articles directly stated a lack of literature on most of the aspects that were relevant for this project (Ferenchick et al., 2019).

RCTs and cohort studies demonstrated different samples, ranging from large (Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019) to small (Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017), and in addition, they focused on different populations (Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017; Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019), which also boosts the quality of the evidence since it suggests that the findings can be applied in different contexts. For all article types, the methodology could be considered a strength, but some specific limitations, for example, the lack of controls in some RCTs could be viewed as an issue. Overall, the presented evidence does support the use of PHQ-9, but multiple sources recommend additional investigation on depression screening in general (Denson & Kim, 2018; Fekadu et al., 2017; Ferenchick et al., 2019; Levis et al., 2020; Ramanuj et al., 2019), which further justifies carrying out the current project.

Application to Practice

The goal is to establish the effectiveness of PHQ-9 as a screening tool for depression specifically in primary care settings. As a result, it can be suggested that the project will provide additional evidence that can be used to develop clinical practice guidelines. However, it can be pointed out that the current clinical practice guidelines recommend using standardized scales for depression assessment, and they also highlight the importance of that assessment (APA, 2016). Thus, the proposed project is in line with clinical practice guidelines that are currently used, and it can contribute to the data that can help follow those guidelines in the future.

EBP Action Plan

Human Subjects Protection

The project did not involve any potential risks for the participants since they were only subjected to screening. However, the issues of confidentiality and protection were taken seriously. Informed consent was a requirement for participation, but the potential participants were informed that no negative outcomes would follow from them refusing to participate. Furthermore, the data was anonymized, with the participants receiving codenames to protect their identity. The data will not be shared with anyone beyond a few generalized descriptions, and it will be fully destroyed in three years.

Population

The population of interest is the people who experience the issue of MDD, specifical adults with MDD. Furthermore, the project also involved the people served by the Orlando primary care clinic, which is why the population attended by it is also the population of interest to the project. It should be pointed out that the patients’ families and communities at large would also be considered stakeholders and expected to benefit from the intervention. However, as can be seen from the PICOT definitions, the actual population of the project is people with MDD, especially those served by the Orlando primary care clinic. Despite the increased risk of depression in the younger population, the project did not explicitly focus on young adults.

Setting

An Orlando primary care clinic, as was mentioned, is the setting of the project. The majority of the population served by the clinic are adults, and the diagnosis of MDD is common enough among them, which is in line with how widespread the issue is, statistically speaking. The goal of the project was to improve the ability of the clinic to serve its population through training and the implementation of an improved screening tool.

The selection of six weeks as the implementation period was mainly associated with time constraints; the project could not dedicate more time. As a result, it is accepted that the findings might not produce a stark and statistically significant difference between the intervention and comparison simply because the time required for properly implementing the intervention might not pass. The goal is to improve and facilitate the process of intervention implementation with the help of a combined theoretical framework discussed below.

Conceptual Theoretical Framework

While the permission to redistribute the copyrighted version of Iowa Model Collaborative et al. (2017) has not been received, the project will use the model for its action plan without its redistribution. Figure 3 represents a transformed version of the model, although it should be pointed out that the original version presupposes the possibility of reiterating steps for improved outcomes. Additionally, Figure 1 can be used to check the ways in which Lewin’s model and the IOWA Model can be combined.

Based on the model, the following steps were undertaken. First, the determination of the issue is important, and it had been made based on the literature and guidelines which demonstrate that it is preferable to employ PHQ-9 in primary care settings (Arrieta et al., 2017; Ferenchick et al., 2019; Hartung et al., 2017; Indu et al., 2018; Korenke et al., 2016; Levis et al., 2019; Levis et al., 2020; Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017; Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019). Since the Orlando clinic does not use PHQ-9 consistently yet, it was helpful to view the situation as an issue that could be resolved. Since the problem of MDD screening is a major one, that particular issue was a priority (Ferenchick et al., 2019), which makes it worthy of focusing a change on during this project.

The change itself required forming a team first and foremost. The chair was Dr. Jennifer Serotta, and the co-chair was Dr. Christina Wright. Additionally, the help of the clinic’s personnel was requested as necessary, and other stakeholders included patients and their families. The formation of the team was followed by reviewing the evidence, and the presentation of the findings could be considered the moment of finding the solution. Furthermore, the planning of the change has been carried out, and the plan can be presented as follows.

Method and Process

It was intended to recruit most of the providers of the clinic for the change, as well as a number of patients (with the intended minimum of 30). The procedures were to include informed consent, lunch and learn (aimed to train them to use PHQ-9), as well as a blinded screening process. The screening involved a provider using PHQ-9 to screen a recruited patient for depression followed by a provider blinded to the results of the PHQ-9 screening conducting a semi-structured interview-based screening for MDD. The participants were also subjected to psychiatric evaluation. This method of PHQ-9 testing is the approach used in some of the literature reviewed for this project (Munoz-Navarro et al., 2017).

The providers were required to report the number of patients attending and the number of patients screened; additionally, the PHQ-9 scores of anonymized patients and the interview-based results were reported. The results of the PHQ-9 and interview-based screening, as well as a psychiatric evaluation, were compared for statistically significant differences (through a non-parametric test described below due to the sample size and differences in data types). For patient safety, aside from the informed consent procedures, the providers were required to carry out the standard procedures for managing suicidal patients should they be found; the data of the patients was supposed to be excluded if incomplete.

Thus, the procedures included both the process of change and the method of evaluating it. Furthermore, the IOWA model requires reporting the results, which is being done in this document. It was also intended to take into account the Lewin’s model of change, which is generally in line with the IOWA model in that it also involves a preparation (unfreezing) and change elements (Lewin & Gold, 1999), both of which took place during the project.

Refreezing, however, is outside of the scope of the project because of its time constraints. Indeed, refreezing requires significant change that needs to be monitored and evaluated, which the present project cannot fit into its timeframe. However, the foundations of refreezing were developed with the help of the above-described processes and reporting as the methods of carrying out and evaluating the change will be established.

To summarize, the project used two models, including the IOWA model and Kurt Lewin’s model, to guide its processes, which included identifying the issue, forming a team, establishing a plan, and implementing and reporting it. The refreezing will take place in the future in case the findings support its implementation.

Data Collection

As it was mentioned, the data collection involved three screening rounds: PHQ-9, semi-structured interviews, and psychiatric evaluation. The data were reported by the providers who performed the screenings or evaluations. The data were anonymized to ensure the protection of the participants.

From the perspective of intervention and outcomes, the following statements can be offered. First, the intervention consisted of introducing PHQ-9. The outcomes involved PHQ-9 screenings taking place, as well as resulting scores. The scores were compared to semi-structured interviews and psychiatric evaluation to determine the potential value of introducing PHQ-9 with the help of the following data analysis plan.

Data Analysis

Data analysis had to employ a non-parametric test due to the small number of people involved. Specifically, Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used to compare the participants diagnosed with MDD during the PHQ-9 round, semi-structured interview round, and the psychiatric evaluation round because the case involved dependent groups with a small sample (Polit & Beck, 2017). The analysis was carried out using specialized software for simplicity’s and accuracy’s sake.

Organizational Factors

The organizational factors could have affected the project in a variety of ways, but the majority of them were positive. Thus, there was little resistance to the project, with most of the participants being interested in implementing PHQ-9. The organizational management was very helpful and accommodating. There were no rewards offered for participation, but still, none of the providers missed the teaching sessions, and everybody provided positive feedback about the training. Thus, the organizational factors facilitated the project.

Outcome Evaluation

Participants

A total of 27 people have been involved in the project because of the restrictions of the time and settings affordable for the project. Only adults were recruited who could consent and did consent to the project’s procedures. The setting of the Orlando primary care clinic provided all the participants of the project.

Descriptive Measures

The majority of the participants (21) were female and in their thirties or forties (24). No people under 18 or over 65 were recruited. See Tables 2 and 3 for details.

Table 2. Demographics: Gender.

Table 3. Demographics: Age.

The participants agreed to participate in the project and were subjected to PHQ-9 screening, semi-structured interviews, and psychiatric evaluation. The former yielded 6 cases for referral; semi-structured interviews yielded four cases, and psychiatric evaluation confirmed 5 cases of mild-to-moderate depression. None of the people who were not referred for psychiatric evaluation through either method were found to have depression based on the psychiatric evaluation. In other words, all the three methods were fairly well aligned with each other, suggesting their validity.

Outcomes

No statistically significant difference was found between any of the sets of diagnoses. With the small sample involved, it is not surprising, though, which is why it is critical to discuss the findings below. Additionally, it should be noted that the providers offered positive feedback regarding the training and considered themselves equipped to perform PHQ-9 screening. Overall, the project was deemed a successful one.

Discussion

No Statistically Significant Difference between PHQ-9 and Psychiatric evaluation

While it is important that the project found no statistically significant difference between the three rounds of diagnosing, which would have implied the psychiatric evaluation confirming PHQ-9 diagnoses and semi-structured interview diagnoses with a bigger sample, the sample was not big. Only five people, in the end, were found to have signs of mild-to-moderate depression, which is definitely not enough for sweeping conclusions.

The fact that there were only five positive cases undermines the ability of the findings to confirm PHQ-9. However, it can be said that the present project does not imply that PHQ-9 is not an effective tool for primary care screening; in fact, it might suggest the opposite given that the referrals from the questionnaire were supported by the psychiatric evaluation. It should also be pointed out that the participants were mostly people in their 30s and 40s, which may have affected the number of people with MDD in the sample; after all, the issue is particularly widespread among younger populations (NIH, 2019). Similarly, the fact that the PHQ-9 is shown to be more effective with older populations might be relevant (Levis et al., 2019). Overall, however, more research is required to replicate or disprove this finding.

On a more significant note, the project involved implementing a standardized method of primary care MDD screening within the given setting, which is an important outcome. Prior to the project, semi-structured interviews were used, which did not have a specific form. Now, the setting’s providers are trained in administering PHQ questionnaires, which is an essential practical outcome of the project. Since it is established in the literature that standardized screenings are preferable, this outcome can be considered theoretically positive. Unfortunately, the presented analysis can offer only preliminary empirical data on the actual effectiveness of the change; for a more specific conclusion, a greater sample is required.

Strength and Limitations

The primary strength of this project is that it describes its methodology in great detail, allowing replicability. Furthermore, the fact that the project involved an actual change in the clinic that served as the project’s setting is a strength. However, there are several limitations to consider, the first of them being the sample size as described above. Furthermore, an important limitation is connected to the fact that the effectiveness of training is a potential confounding variable that was not truly controlled during this project. Finally, the fact that the data were reported by providers and may have been subject to human error should be considered.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Transferability

The project has limited transferability. It involved one clinic with a very limited number of providers, and the number of patients was not very large either. As a result, it might not be appropriate to assume that the findings are transferable, even though they are generally in line with the relevant literature (Arrieta et al., 2017; Ferenchick et al., 2019; Hartung et al., 2017; Indu et al., 2018; Korenke et al., 2016; Levis et al., 2019; Levis et al., 2020; Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017; Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019).

The findings are applicable to the specific setting of the project though, and since the goal was to achieve a change in that setting, it is appropriate. The limitations still apply, but the findings do not suggest that PHQ-9 is not a suitable tool for screening, and now, the setting’s providers are trained to use a standardized method. More research is required for generalizable statements, but the implications of the project for practice are still significant.

Implications for Future Research

The project suggests that PHQ-9 might be a useful screening tool, or, rather, it would have suggested that if the project’s sample was large enough. That is in line with the relevant literature (Arrieta et al., 2017; Ferenchick et al., 2019; Hartung et al., 2017; Indu et al., 2018; Korenke et al., 2016; Levis et al., 2019; Levis et al., 2020; Munoz-Nevarro et al., 2017; Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019). However, more research is definitely required for more generalizable statements, as well as for the effects of the introduction of PHQ-9 into the settings.

Conclusion

The general intention of the project was to provide the clinic with a better evidence-based tool for screening depression with the ultimate goal of improving the well-being of the patients and their community. While it is reported that the use of screening on its own is not leading to improved patient outcomes, together with suitable interventions, better screening is likely to lead to a better, more stable community. It was not expected that this outcome would be achieved within the scope of the presented project, but it was supposed to offer the foundations for the refreezing of the change, provided that it is shown to be helpful.

In summary, the presented project was an evidence-based practice change that employed quantitative methods of data analysis to determine the effectiveness of PHQ-9 when compared to the previously employed methods of the Orlando primary care clinic in adults below the age of 65. Based on the literature review, depression is a major concern, and MDD screening remains lacking in primary care, while the research on the topic is not conclusive. As a result, the project covered an important and relatively understudied area while employing an evidence-based intervention. Indeed, PHQ questionnaires are evidenced to be superior to interviews, and they are recommended as MDD screening tools based on the presented literature.

Furthermore, the literature recommends providing sufficient training to the providers involved in PHQ-9 administration. As a result, based on Lewin’s model and the IOWA model, the project offered training to the providers involved in the project and based on the literature reviewed, it also employed a blinded design, with providers using PHQ-9 and semi-structured interviews, as well as psychiatric evaluations, with the same recruited patients. The findings might not be sufficient for proving the effectiveness of PHQ-9, with more research required for that, but there were no statistically significant differences detected between any of the screenings. With the small sample, the findings cannot be considered conclusive.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder (5th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (2016). Practice guidelines for the psychiatric evaluation of adults (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (2017). Depression screening rates in primary care remain low. Web.

Arrieta, J., Aguerrebere, M., Raviola, G., Flores, H., Elliott, P., Espinosa, A.,… Franke, M. F. (2017). Validity and utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)‐2 and PHQ‐9 for screening and diagnosis of depression in rural Chiapas, Mexico: A cross‐sectional study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(9), 1076-1090. Web.

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2018). Mental health. Web.

Denson, B., & Kim, R. (2018). Evaluation of provider response to positive depression screenings and physician attitudes on integrating psychiatric pharmacist services in primary care settings. Mental Health Clinician, 8(1), 28-32. Web.

Fekadu, A., Medhin, G., Selamu, M., Giorgis, T. W., Lund, C., Alem, A.,… Hanlon, C. (2017). Recognition of depression by primary care clinicians in rural Ethiopia. BMC Family Practice, 18(1). Web.

Ferenchick, E., Ramanuj, P., & Pincus, H. (2019). Depression in primary care: part 1—screening and diagnosis. BMJ, 365(1794), l794. Web.

Hartung, T. J., Friedrich, M., Johansen, C., Wittchen, H. U., Faller, H., Koch, U., … Mehnert, A. (2017). The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) and the 9-item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as screening instruments for depression in patients with cancer. Cancer, 123(21), 4236–4243. Web.

Indu, P. S., Anilkumar, T. V., Vijayakumar, K., Kumar, K. A., Sarma, P. S., Remadevi, S., Andrade, C. (2018). Reliability and validity of PHQ-9 when administered by health workers for depression screening among women in primary care. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 37(1), 10–14. Web.

Iowa Model Collaborative, Buckwalter, K. C., Cullen, L., Hanrahan, K., Kleiber, C., McCarthy, A. M.,… Tucker, S. (2017). Iowa model of evidence-based practice: Revisions and validation. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(3), 175-182. Web.

Kamenov, K., Cabello, M., Nieto, M., Bernard, R., Kohls, E., Rummel-Kluge, C., & Ayuso-Mateos, J. (2017). Research recommendations for improving measurement of treatment effectiveness in depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(356), 1-9. Web.

Kroenke, K., Wu, J., Yu, Z., Bair, M.J., Kean, J., Stump, T., & Monahan, P.O. (2016). Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety and Depression Scale: Initial validation in three clinical trials. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(6), 716-727. Web.

Levis, B., Benedetti, A., & Thombs, B.D. (2019). Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ, 365, l1781. Web.

Levis, B., Sun, Y., He, C., Wu, Y., Krishnan, A., Bhandari, P. M., … Thombs, B. D. (2020). Accuracy of the PHQ-2 alone and in combination with the PHQ-9 for screening to detect major depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(22), 2290–2300. Web.

Lewin, K., & Gold, M. (1999). The complete social scientist: a Kurt Lewin reader. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Li, H., Luo, X., Ke, X., Dai, Q., Zheng, W., Zhang, C., … Ning, Y. (2017). Major depressive disorder and suicide risk among adult outpatients at several general hospitals in a Chinese Han population. PLOS One, 12(10), 1-15. Web.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Muñoz-Navarro, R., Cano-Vindel, A., Medrano, L. A., Schmitz, F., Ruiz-Rodríguez, P., Abellán-Maeso, C.,… Hermosilla-Pasamar, A. M. (2017). Utility of the PHQ-9 to identify major depressive disorder in adult patients in Spanish primary care centres. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 291. Web.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2019). Major depression. Web.

Ramanuj, P., Ferenchick, E., & Pincus, H. (2019). Depression in primary care: part 2—management. BMJ, 365(1835), l835. Web.

Stahl, S. M. (2013). Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. Web.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). National Survey on Drug Use and Health – 2020. Web.

Villarreal-Zegarra, D., Copez-Lonzoy, A., Bernabé-Ortiz, A., Melendez-Torres, G., & Bazo-Alvarez, J. (2019). Valid group comparisons can be made with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A measurement invariance study across groups by demographic characteristics. PLOS ONE, 14(9), e0221717. Web.

World Health Organization. (2020). Depression. Web.

Zaccagnini, M., & Pechacek, J. M. (2019). The doctor of nursing practice essentials: A new model for advanced practice nursing. New York, NY: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Appendix A

Evidence Synthesis Table: Key Articles and Additional Research.

Note: RCT – randomized controlled trial, PHQ – patient health questionnaire, CFA – confirmatory factor analysis.